Barclays in Crisis: Should the Government's Banking Inquiry be Parliamentary or Public?

With squabbles between the government and Labour benches, quelle surprise, about whether the proposed parliamentary inquiry into banking should be a public one instead, many are left asking what the difference is and, more importantly, which is better.

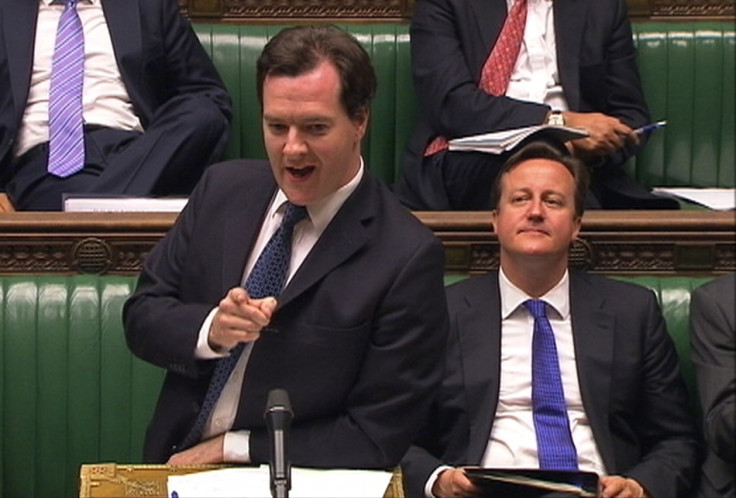

Chancellor George Osborne told the House of Commons that the government wants both MPs and Peers to sit on the inquiry committee, which is being set up in the wake of the Barclays rate-fixing scandal. Ed Miliband, the Labour leader, disagrees and wants to take a judicial approach to a banking probe.

"This is about the culture and practices of the entire banking system which is why we need an independent, open, judge-led, public inquiry," he said.

It must be a parliamentary inquiry, argues the government, because it will be cheaper, faster, and more forensic than a public one. Andrew Tyrie, the Tory MP for Chichester and chairman of the Commons Treasury select committee, is likely to lead the parliamentary inquiry.

"The advantage of a parliamentary inquiry is speed. You get things done quickly," Professor George Jones, an expert on Britain's political system at the London School of Economics, told International Business Times UK.

Banking inquiry 'must finish by January'

Prime Minister David Cameron said having a parliamentary probe would mean the committee could reach their conclusions by January, when the government's Finance Bill is debated in parliament.

Cameron intends to incorporate the inquiry's recommendations into the Finance Bill and so it must finish by the time the banking reforms reach parliament for debate at the start of 2013.

He also said that the inquiry will have access to all of the documentation, files, and ministers it needs.

A public inquiry would take "months to set up", claimed Osborne, and could take as long as a couple of years to complete.

Jones cited the Bloody Sunday public inquiry, which "cost millions and went on for years", as an example of how public inquiries can drag on.

"If you have a full public inquiry headed by a judge - with legal representation, cross examination, people on oath, behaving almost as if it is a court - you get no speed," he said.

"That's the danger of having that sort of investigation.

"It takes a long, long time, and who knows when it could end? Unless a very firm date is given. But the judge could say that doesn't give them enough time to do justice to the case, to hear all sides and to conduct the examination that they want."

Politics of inquiries

There is also something to be said for people with political understanding taking on the inquiry, according to Jones.

"They will be very sensitive to the politics of it all and the needs of public policy," he said.

"The disadvantage of the judicial inquiry is the judge does tend not to have an inside knowledge of the politics of the matter, and stresses formality and, of course, law."

Jones notes that there are people who see the inherently political nature of parliamentary inquiries as a significant problem.

"They think that makes it more political and that the public wouldn't trust a highly politicised select committee, and you wouldn't get out of the select committee anything really critical if government was involved - they would pull their punches," he said.

Independence is vital, they say, because of the conflict of interest between many politicians and the financial services industry.

Many donations to politicians and their parties, particularly the Conservatives, have come from the banking industry.

Government dominating the committee

Critics also argue that the government will inevitably give itself a dominant presence in the parliamentary inquiry, because the political composition of the committee, which it appoints, will reflect the make-up of the House of Commons.

"If it is to be cross-party there will be considerable consultation between the party whips and the party leaders," Jones said.

"The hope is that there would be a unanimous agreement."

First though, the government must get parliamentary approval for the inquiry - from both the Commons and Lords.

"That's not going to be a problem. The government has got a large majority in the House of Commons," Jones said.

"It hasn't got such a sure majority in the House of Lords, with cross benchers it depends on which way they go.

"But I would have thought they would support the government over this."

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.