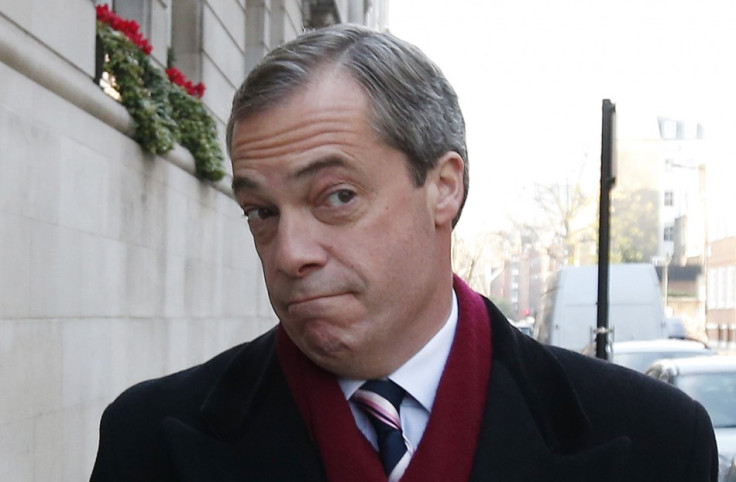

Ukip's Nigel Farage Learns New Labour Lesson to Weed out Mavericks

There is one inevitable challenge for any political party that bases its appeal on being anti-establishment, as Nigel Farage proved during Ukip's spring conference.

The more successful you become, the more you start to behave like the establishment.

Specifically, Farage told any audience or interviewer who asked that he did not want his party to become so controlling and intolerant of its mavericks that it started to adopt a New Labour-style approach to management.

But then, as he once again struggled to answer some pointed questions about some of his members' beliefs and behaviour, he confirmed he had imposed a new set of rules for would-be candidates demanding they sign a pledge they have no skeletons in their cupboards.

"We're trying to screen out people who would be a huge distraction, and that doesn't mean I want to turn it into New Labour and we must think the same thing," he told the BBC's Marr show.

But his new pledge echoes the infamous "Mandelson Rules" introduced by the former Labour spin doctor in a bid to weed out anyone who could embarrass the party, by being too left-wing for example, by asking candidates if there was anything in their past that could "bring the party into disrepute".

The Ukip pledge asks the very same question, along with seeking a declaration that candidates have never "engaged in, advocated or condoned racist, violent, criminal or anti-democratic activity".

It asks: "Are you or have you ever been a member of the BNP, EDL or any other organisation that might be of public interest?"

And candidates must agree: "I have never been a member of or had links with any organisation, group or association which the national executive committee considers is liable to bring the party into disrepute.

"I do not have any 'skeletons in my cupboard' that may cause me or Ukip embarrassment if they were to come out during the election."

There are similar rules in place for all the mainstream political parties, so Ukip is no different, except in some of the specifics. For example the reference to the BNP and EDL are of particular significance to Farage who has faced routine claims his party attracts people sympathetic to those groups.

The problem was further underlined by the routine of stand up comic Paul Eastwood who allegedly made a series of jokes about Poles, Muslims and Somalis during a show at the conference.

The jokes themselves may or may not have been offensive, but the fact he thought this was an audience that would particularly appreciate them speaks volumes.

So the dilemma for Farage is sharp. He is well aware that much of his growing popularity is based on the fact Ukip is "not like the rest of them". But as he edges closer to his hoped-for political breakthrough, he runs the risk of looking just like the others.

His Spring conference may have been a big step in that direction, but there are other hurdles ahead.

In particular, beyond the two issues that most attract people to Ukip – immigration first and EU withdrawal second – the party manifesto remains a work in progress.

Farage has promised to start filling in those blank pages after the EU elections in May, itself an interesting comment on what he believes are the only issues in those elections.

When he does eventually provide that manifesto he will have to make detailed promises on specific policy areas – just like all the other political parties.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.