Unique Antarctic ecosystem transformed as polar deserts flooded in heatwave

The McMurdo Dry Valleys were flooded as summer temperatures soared to 12C.

Just one intense season of warm weather in a polar desert in Antarctica was enough to trigger a transformation in the region that has lasted for decades.

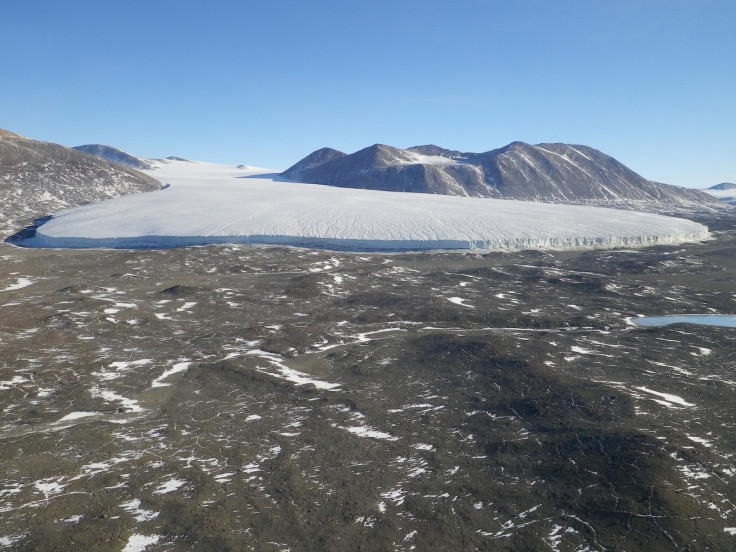

The McMurdo Dry Valleys form a large and unique polar desert. It is made up of the largest ice-free zones on the continent. A 25-year project has been investigating the valleys for changes in atmospheric and ecological conditions.

One abnormally warm summer in 2002 changed the overall trajectory of the ecosystem, finds a study now published in the journal Nature Ecology & Evolution. The weather caused glacial melt on a scale that hadn't been seen in the region for more than 30 years.

The heatwave came after a period of progressive cooling from 1987 to 2000, of about -0.7C per decade. The ice in the region thickened and there was less and less surface meltwater in streams.

Warm föhn winds blowing from the Southern Ocean led to surging temperatures, reaching as high as 12C. Glaciers melted and the usually dry valleys were flooded.

"This flood year was the pivot point," said study author Michael Gooseff of the University of Colorado, Boulder's Institute of Arctic and Alpine Research. "Prior to that, all physical and biological indicators had been moving in the same direction."

The ecosystem had a complex longer-term reaction to the event. Some changes, such as stream flows, were boosted for a full 15 years afterwards. But algae in the region took about three years before their populations responded by increasing.

The fact that just one season of much warmer weather was enough to push the ecosystem out of this pattern illustrates the immense sensitivity and responsiveness of the ecosystem, the researchers say.

"These community responses to the observed climate changes demonstrate complexity, variability and step changes and reveal that the effects of short-term extreme events can be measured in ecosystems for many subsequent years," Dana Bergstrom of the Australian Antarctic Division of the Australian government's Department of the Environment and Energy writes in a comment piece in the journal.

"It has recently been argued that there are considerable gaps in our knowledge regarding the responses of biodiversity to a changing world – specifically, how ecosystem function will respond to the changing compositions of species that are the result of climate change and other anthropogenic drivers.

"Long-term research studying simple ecosystems, away from other anthropogenic pressures such as habitat loss and point-source pollution, contribute substantially towards filling this gap."

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.