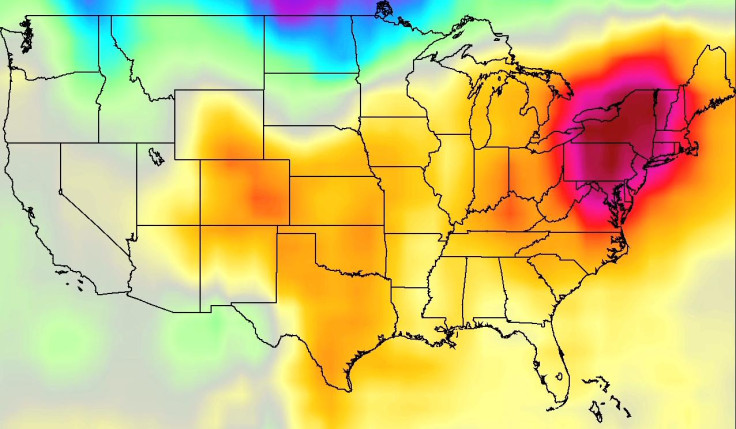

US record high temperature forecasts for the future are out

Previous models overestimated how much record high temperatures would be affected by warming climate.

A warming climate will bring with it fewer obvious markers of record high temperatures in the US than previous climate models estimated, a team of scientists has found.

The study published in the journal PNAS looked at observational records from 1930 to 2015 of record highs and lows, and matched that to the overall average warming that's already been measured. The study proposes a new way to project long-term climate trends in the US.

Observational records from the 20th Century were compared with the predictions of established climate models of the ratios of record high and low temperatures. The climate models tended to predict that there would be a higher ratio of record highs to record lows than was actually observed in the 20th Century, the study found.

"Once we had that empirical relationship we could just project that forward for future levels of warming. So that's one way of estimating what the future ratio of the records could be in the future," study author Gerald Meehl of the National Center for Atmospheric Research in the US told IBTimes UK.

How often record high temperatures come along is closely related to how much the climate has warmed, he says. A smaller shift towards more record high temperatures shows that we are actually further along into climate change than previous models would suggest – as average temperatures increase, the change will appear more subtle in relation to day-to-day record highs than predicted.

"The fact is that the odds are shifting towards record high temperatures versus record lows," Meehl says. "If there's no average warming you'd have an equal chance of setting a record high or record low at any given [weather] station, so the ratio would be about 1:1. But as the average temp increases you start shifting the odds of setting a record high maximum temperature as opposed to record low minimum temperature."

The ratio of record highs to lows has been increasing – for the first decade of the 21st Century it's been about two record highs for every record low, Meehl says.

The climate models were off because they assumed that the soil in the US was a little drier than precipitation records suggested it would be, Meehl says. Drier soil means that there is less cooling from evaporation, leading to higher temperatures and greater chance of a record high. In fact, soils were wetter and brought down the likelihood of a record high.

In 2016 the ratio of record highs to lows has been about 6:1, as it's been a very warm year. In the future, we can expect fewer record highs as the climate warms than existing models predict, Meehl says.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.