Velociraptor snouts grown on chickens in Frankensteinosaurus experiment

Scientists have successfully grown a dinosaur beak on a chicken in a laboratory.

Led by Yale palaeontologist Bhart-Anjan S. Bhullar and Harvard developmental biologist Arhat Abzhanov, the team managed to replicate the molecular process that saw dinosaur snouts becoming the very first bird beaks.

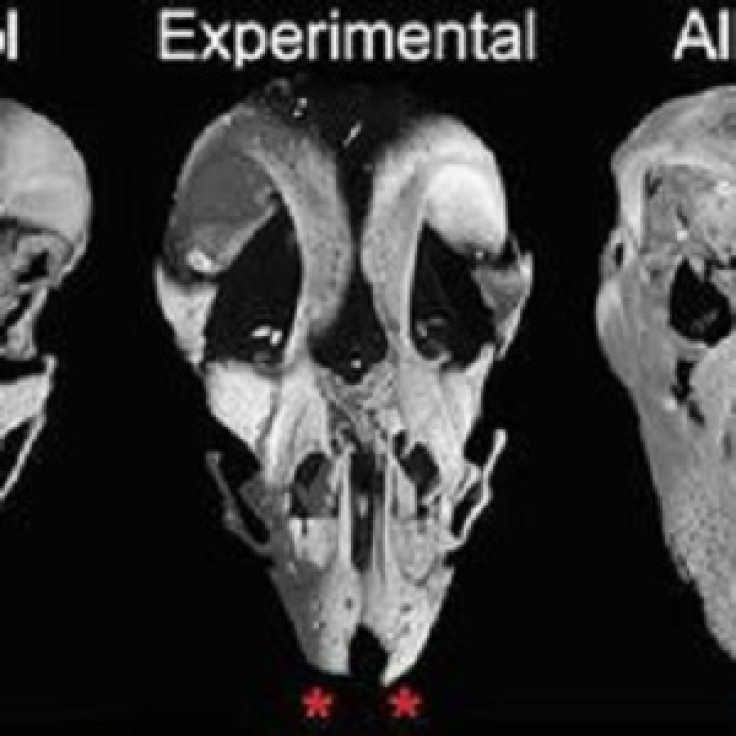

Publishing their findings in the journal Evolution, the team used fossil records as a guide to copy the ancestral molecular development to transform chicken embryos into specimens that had a dinosaur snout and palate.

The dinosaur snouts it would have most closely resembled would have been the Velociraptor and Archaeopteryx.

Bhullar said: "Our goal here was to understand the molecular underpinnings of an important evolutionary transition, not to create a 'dino-chicken' simply for the sake of it."

He said the beak is a vital part of the bird feeding apparatus. It is the part of the avian skeleton that has diversified most extensively and radically over time. "Yet little work has been done on what exactly a beak is, anatomically, and how it got that way either evolutionarily or developmentally," he added.

In their study, the team tried a new approach to finding the molecular mechanism involved in creating the skeleton of the beak. They analysed the anatomy of related fossils to get an idea about the transition, then looked for shifts in the gene expression that correlated with it.

They looked at the embryos of emus, alligators, lizards and turtles. Findings showed birds have a unique median gene expression zone of two different facial development genes early on in embryonic development compared with non-bird reptiles and mammals.

Researchers then used small-molecule inhibitors to eliminate the activity of the proteins produced to induce the ancestral molecular activity and the ancestral anatomy.

The beak structure reverted and the palatine bone on the roof of the mouth went back to its ancestral state. "This was unexpected and demonstrates the way in which a single, simple developmental mechanism can have wide-ranging and unexpected effects," Bhullar said.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.