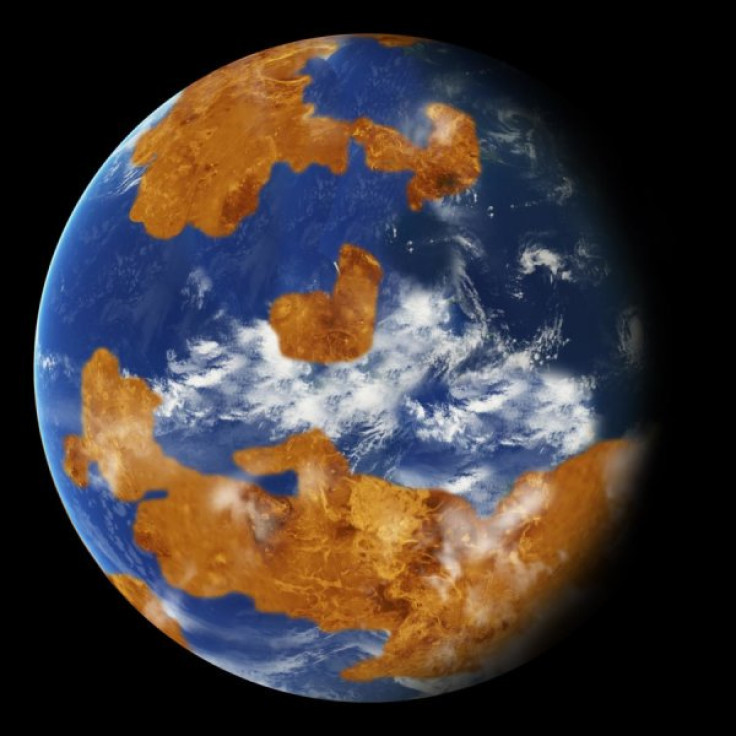

Venus may have been habitable in its early history

Shallow oceans of liquid-water could have been present on the planet's surface.

With temperatures soaring to 462 degrees Celsius on its surface and a suffocating carbon dioxide atmosphere 90 times as thick as Earth's, life as we know it cannot survive on Venus. However, researchers from NASA's Goddard Institute for Space Studies (GISS) have used computer modelling to paint a picture of the planet's early climate with some surprising results. Their simulations show that, for up to two billion years of its early history, the planet may have had shallow oceans of liquid-water and surface temperatures possibly even a few degrees cooler than Earth today.

"Many of the same tools we use to model climate change on Earth can be adapted to study climates on other planets, both past and present," said Michael Way, a lead author of the study and researcher at GISS. "These results show ancient Venus may have been a very different place than it is today."

The findings from the study have been published in the journal Geophysical Research Letters.

Long-held theories about Venus' geophysical evolution have suggested that the planet was formed out of similar materials to Earth, although the way its climate has developed has differed because it is closer to the sun. Data from NASA's Pioneer mission in the 1980s first led scientists to suggest that Venus could have had an ocean, however, because of its proximity to the sun, these early oceans evaporated. Water vapour molecules were also split apart by ultraviolet radiation with the hydrogen escaping into space. This resulted in a situation where carbon dioxide built up in the atmosphere, creating a runaway greenhouse effect which led to the current atmospheric conditions.

Previous studies have shown that the rotation speed of a planet and its topography can be factors in determining whether it is habitable or not. Venus rotates relatively slowly – one day on Venus is equivalent to 117 Earth days. Scientists thought this could be explained by its thick atmosphere, however, recent research has suggested that a similar rotation speed could be possible with a thinner, Earth-like atmosphere as well.

GISS researchers have hypothesized that ancient Venus had more dry land than Earth, especially in tropical regions. This situation would naturally have limited the water evaporating from the oceans, meaning a reduced greenhouse effect and, consequently, a more habitable planet.

The GISS computer models simulated a hypothetical early Venus with a shallow ocean, an Earth-like atmosphere and a day length similar to the current one. Measurements from NASA's Magellan mission in the 1990s were used to add topographical information to the model. The ancient sun was also 30% dimmer than it is now so this was also factored in to the calculations, although ancient Venus would have still received around 40% more sunlight than Earth does today.

"In the GISS model's simulation, Venus' slow spin exposes its dayside to the sun for almost two months at a time," co-author and GISS researcher Anthony Del Genio said. "This warms the surface and produces rain that creates a thick layer of clouds, which acts like an umbrella to shield the surface from much of the solar heating. The result is mean climate temperatures that are actually a few degrees cooler than Earth's today."

The study was conducted as part of NASA's Planetary Science Astrobiology program and the Nexus for Exoplanet System Science which are initiatives designed to foster interdisciplinary collaboration in the search for life on other planets. The new findings will have direct implications for upcoming NASA missions like the Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite, which will attempt to detect potentially habitable planets.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.