Warlords of Ivory: Investigation looks at elephant poaching business with fake tusks and a GPS device

The ivory trade is big business, with thousands of elephants slaughtered every year by poachers trafficking their tusks into East Asia. However, how they get there is less clear.

Earlier this year, researchers from the University of Washington found two main poaching hotspots in Africa – Tanzania and nearby parts of Mozambique and the Tridom, which includes parts of Gabon, the Republic of Congo and Cameroon.

However, how it gets from national parks to China and other countries where demand is high is a complicated process – and a new investigation shows it is even more complex than once thought. Bryan Christy commissioned fake elephant tusks and fitted them with a GPS device to monitor them after being introduced into the illegal market.

He told IBTimes UK: "I had started that process two years earlier … all the samples I got back looked like a tusk, but when you touched them and held them you knew they were fake. I did a story on taxidermists and researching that I met many of the world's best and one of those guys was George Dante.

"I told him 'I have an idea, but you've got to keep your mouth shut'. And he loved the idea so he worked really hard on it. I'm very critical of every element of my investigations and I was very surprised [with how realistic the tusk was]. The first sample was great."

The tusk was so believable that when arriving in Dar Es Salaam Airport he was stopped and searched by police: "Certainly it wasn't good for me personally. But on the other hand, it was great that I saw no signs at that point they were corruptible."

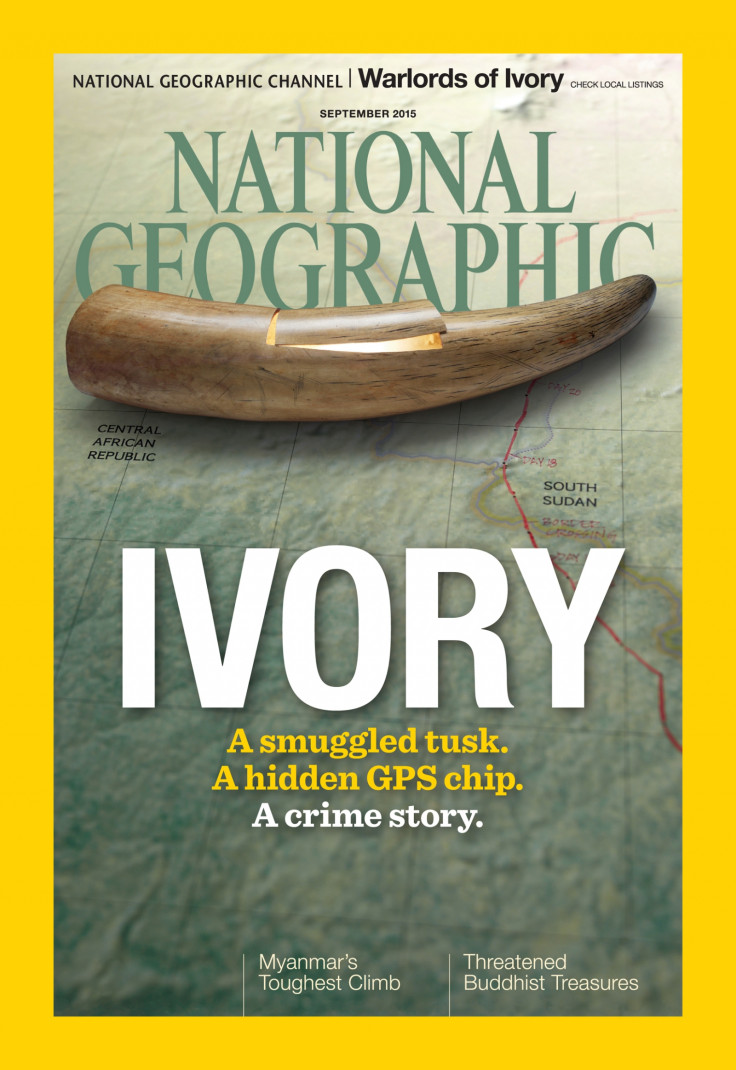

Christy's investigation is the cover story on the latest issue of National Geographic and is subject of the documentary Warlords of Ivory, which will be aired on the National Geographic channel on 30 August. After dropping them into Congo's Garamba National Park, he and the team watched and waited for the tusks to start moving.

"I just thought 'oh well this isn't going to work'. It was several weeks before it started moving. These tusks operate like an investigator, like a member of the team. You put them out in the world and you don't know what they're doing except that they're not moving. Then once they do move they're going places and seeing things no one has ever seen, they're being exchanged and carried by people. It was very exciting from that perspective."

Much to his surprise, the fake tusks were taken north to Sudan, rather than east for shipping out of the continent. "Basic economics says it should move as quickly as possible to a large port to get off the continent, but it didn't go east it went north," he said.

The investigation quickly an inherent link between ivory poaching and terrorism. The tusks went directly to the town Joseph Kony and the Lord's Resistance Army uses to trade ivory.

"The biggest shock was the level of violence in central Africa," Christy said. "Not just over ivory, but these are militia and terrorist groups killing park rangers not just for the ivory but because they represent order in these places. In order to get to villages they were killing rangers and likewise the rangers consider themselves the protectors of the villagers.

"I don't think villagers aware of the international trade issue. They're not aware of smuggling. They know elephants are being killed. They're afraid to go into Garamba National Park because the LRA occupies it and has kidnapped people and dragged them in.

"The park represents something frightening and that's true of other places. Destinations westerners save up and fly over to watch gorillas or elephants and lions, but locals see it as a frightening place, not just because of the animals but the people who hide there."

Similarly, he said the level of corruption was shocking. At one point, officials in the Congo tried to get them to pay hundreds of thousands of dollars. To that end, Christy said he had half expected the tusks to end up in government possession – and to come back out into the open market.

"I thought if the authorities grab it I would be able to see – if it goes to a police station or government repository – I thought that would be fascinating mostly to see if it comes out again. The odds are pretty good in most of these places that it will come back out. Then I wanted to see exactly where it went.

"The last I heard from the tusks they were in Sudan and they could be on their way and just in a container unable to communicate, or the batteries could have died, they might have been discovered, they could be hidden inside a house there." He said they have estimated the batteries will last until the end of the year and that he will continue to watch them for signs of movement until then.

Overall, however, Christy said the investigation has highlighted the complicated picture of the ivory trade in Africa. "I think this is certainly it's fair to say that these have shown a light on an aspect of the ivory trade that has been ignored or not understood and that is the role of rebel militia and terrorist groups in central Africa," he said. "They go directly to the town that Joseph Kony is believed to be using as the trading point for ivory.

"We hear these terrible figures every year, and people don't know what to do. But if you look behind the numbers and tell stories about the violence behind the trade… when you tell the stories, people can identify things they can fix.

"China recently said it's going to do away with the ivory market and its stories like this that give them reason. Otherwise, they have no understanding of why people are keen to stop the ivory trade. If you can see the violence you can understand that."

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.