What is fascism? Its much-debated meaning and definition

US President Donald Trump is often accused of being a fascist. But is that the case?

What is fascism? You can ask 10 different people and get 10 different answers.

But despite being largely seen as a 20th-century phenomenon, when it reached its terrible ideological zenith in Nazi Germany, it's a question being asked frequently again amid panic that fascism is re-emerging as a significant political force – albeit in a different shape to what came before.

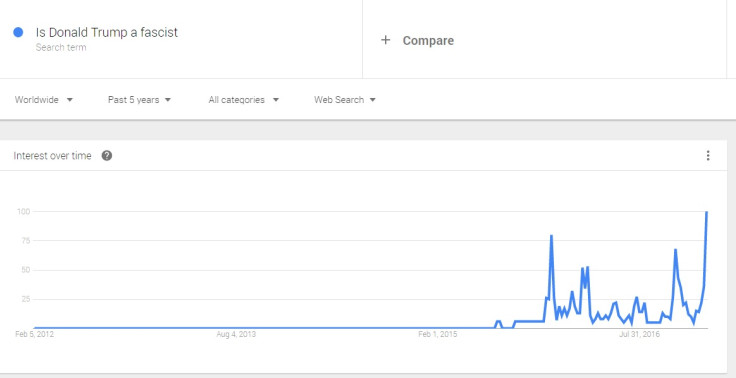

In particular, the question 'Is Donald Trump a fascist?' is increasingly searched for on the internet.

The Republican US president faces accusations that he embodies a kind of neofascism for the 21st century, with his so-called 'Muslim ban', loose attitude to facts, and an economic policy centred on populist nationalism.

While Trump's slogan of 'America First' sounded to his supporters like a welcome rally-cry for a patriotic nation state that looks after its own before outsiders, to others it contained grim echoes of the Nazi-sympathising Americans who used the same rhetoric in the 1930s.

The literal dictionary definition of fascism according to Merriam-Webster is:

1. a political philosophy, movement, or regime (as that of the Fascisti) that exalts nation and often race above the individual and that stands for a centralised autocratic government headed by a dictatorial leader, severe economic and social regimentation, and forcible suppression of opposition

2. a tendency toward or actual exercise of strong autocratic or dictatorial control

But to some people, a literalist definition of fascism is far too rigid because it can contain many different features, some of which can be in contradiction. It was a subject tackled by the journalist and author George Orwell in his 1944 essay What is Fascism?. Orwell bemoaned its slippery use, saying he had seen it applied to Gandhi, farmers, dogs and astrology, among other things:

Yet underneath all this mess there does lie a kind of buried meaning. To begin with, it is clear that there are very great differences, some of them easy to point out and not easy to explain away, between the régimes called Fascist and those called democratic. Secondly, if 'Fascist' means 'in sympathy with Hitler', some of the accusations I have listed above are obviously very much more justified than others. Thirdly, even the people who recklessly fling the word 'Fascist' in every direction attach at any rate an emotional significance to it.

By 'fascism' they mean, roughly speaking, something cruel, unscrupulous, arrogant, obscurantist, anti-liberal and anti-working-class. Except for the relatively small number of fascist sympathisers, almost any English person would accept 'bully' as a synonym for 'fascist'. That is about as near to a definition as this much-abused word has come.

But fascism is also a political and economic system. Why, then, cannot we have a clear and generally accepted definition of it... All one can do for the moment is to use the word with a certain amount of circumspection and not, as is usually done, degrade it to the level of a swearword.

Sales of the political theorist Hannah Arendt's seminal 1951 book The Origins of Totalitarianism have rocketed since Trump took office in the US. Orwell's 1984, first published in 1949, has also re-entered the Amazon best-sellers list. In one oft-cited passage from Arendt's Origins, she describes the type of mass-public needed for a dictator to rise in a society:

The term 'masses' applies only where we deal with people who either because of sheer numbers, or indifference, or a combination of both, cannot be integrated into any organisation based on common interest, into political parties or municipal governments or professional organisations or trade unions. Potentially, they exist in every country and form the majority of those large numbers of neutral, politically indifferent people who never join a party and hardly ever go to the polls.

The Italian writer Umberto Eco, who grew up under Mussolini, considered by many as the godfather of fascism, came up with a 14-point checklist for defining fascism. He wrote in a 1995 essay for the New York Review of Books:

Fascism was a fuzzy totalitarianism, a collage of different philosophical and political ideas, a beehive of contradictions.... But in spite of this fuzziness, I think it is possible to outline a list of features that are typical of what I would like to call Ur-Fascism, or Eternal Fascism. These features cannot be organised into a system; many of them contradict each other, and are also typical of other kinds of despotism or fanaticism. But it is enough that one of them be present to allow fascism to coagulate around it.

Eco gives an explanation for each of his 14 points, which are worth reading – but in short they are:

- Cult of tradition

- Rejection of modernism

- Action for action's sake

- Disagreement is treason

- Exploiting and exacerbating the natural fear of difference

- Appeal to a frustrated middle class

- Obsession with a plot

- Feel humiliated by enemies but able to overwhelm them

- Life is permanent warfare

- Contempt for the weak and popular elitism

- Everybody is educated to become a hero and want a hero's death

- Machismo

- Selective populism

- Ur-Fascism speaks Newspeak [from Orwell's 1984]

Under the 'selective populism' feature of Eco's Ur-Fascism, he gave a prophetic vision of the demagoguery to come in the 21st century:

There is in our future a TV or internet populism, in which the emotional response of a selected group of citizens can be presented and accepted as the Voice of the People

So if fascism arrives in America, what would it look like? There's a quote often misattributed to the American writer Harry Sinclair Lewis, which goes: "When fascism comes to America, it will be wrapped in the flag and carrying a cross."

Nobody seems to know where the quote really comes from, though the debunking website Snopes suggests it may have stemmed from a book called As We Go Marching, published in 1944. The book was written by the journalist John Thomas Flynn, a founder of the America First Committee and an opponent of US entry into the second world war. He wrote:

It is assumed that because the Nazi movement in Germany and the fascist movement in Italy began with small groups of nobodies led by unimportant people, fascism will come in the same way here. It is, of course, possible that the great American fascism may rise thus... But when fascism comes it will not be in the form of an anti-American movement or pro-Hitler bund, practising disloyalty. Nor will it come in the form of a crusade against war. It will appear rather in the luminous robes of flaming patriotism; it will take some genuinely indigenous shape and color, and it will spread only because its leaders, who are not yet visible, will know how to locate the great springs of public opinion and desire and the streams of thought that flow from them and will know how to attract to their banners leaders who can command the support of the controlling minorities in American public life. The danger lies not so much in the would-be Fuhrers who may arise, but in the presence in our midst of certainly deeply running currents of hope and appetite and opinion. The war upon fascism must begin there

In the US Holocaust Museum.

— Sarah Rose (@RaRaVibes) January 30, 2017

I'm shook. pic.twitter.com/EeuHEXWusE

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.