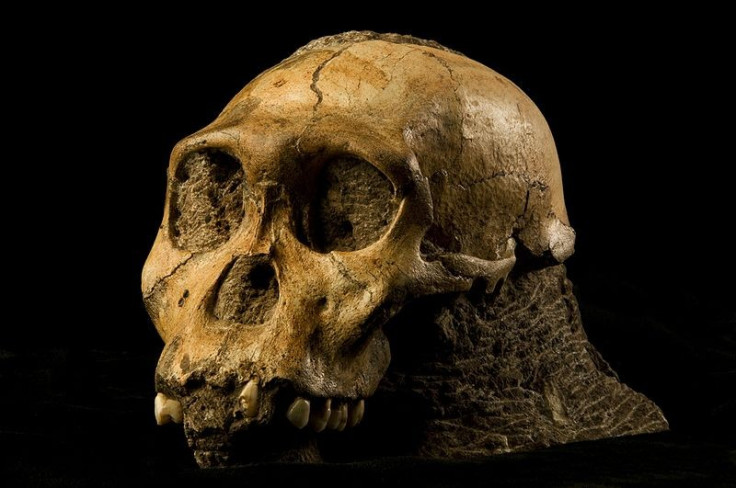

Ancestors of Humans Who Lived Two Million Years Ago Ate Leaves and Wood

Bark and woody tissues were found on the teeth of two skeletal remains of Australopithecus sediba, a hominin species that existed two million years ago

There have been several studies about and inquiries into what our human ancestors ate as part of their regular diet. A new piece of research would seem to indicate it has some answers about hominins who lived two million years ago.

A team of nine scientists from across the world claim to have discovered what they call the first direct evidence of what earliest human ancestors actually ate. The information was announced by the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, which led the project, on Wednesday.

The researchers examined teeth recovered the remains of an elderly female and young male of Australopithecus sediba, a species that existed two million years ago. The significant discovery was bark and woody tissues found on the teeth of both individuals; a find of this kind has never been documented in the research of hominins.

"The find is unprecedented in the human record outside of fossils just a few thousand years old. It's the first truly direct evidence of what our early ancestors put in their mouths and chewed - what they ate," professor Lee Berger of the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg, South Africa, who led the study, said.

Berger realised the stains on the teeth of the skeletal remains were probably dental plaque or calculus, which is mineralised material that forms on teeth. Further carbon dating of the teeth and the plaque showed these human ancestors consumed parts of trees like bark and leaves, as well as sedges, shrubs or herbs, rather than grass.

"Personally, I found the evidence for bark consumption the most surprising," said Berger, adding, "While primatologists have known for years that primates, including apes, eat bark as a fall-back food in times of need, I really hadn't thought of it as a dietary item on the menu of an early human ancestor."

According to researchers, the findings indicate Australopithecus sediba had a diet that was somewhat unexpected, when compared with diets of similarly aged early African hominins, the German research institute said.

"The results suggested a different diet than we have found in other early hominins, and were rather like what we find in living chimpanzees," Matt Sponheimer of the University of Colorado, Boulder, co-author of the research report and a co-researcher said.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.