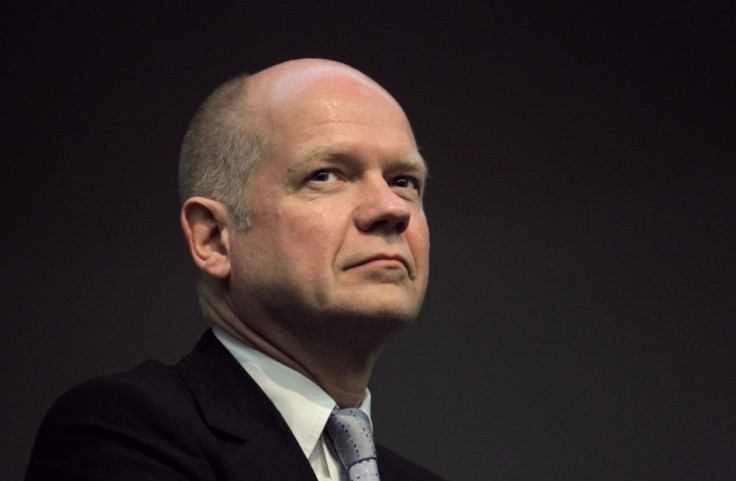

William Hague: There's 'no right to absolute privacy' for British citizens

When it comes to the balance between security and privacy, former UK foreign secretary William Hague believes there can be "no absolute right" to privacy for British citizens.

In a keynote address to a packed London hall at Infosecurity Europe, Hague spoke about intelligence gathering by spies at GCHQ, the government's stance on strong encryption and how former NSA-contractor-turned-whistleblower Edward Snowden had aided terrorism.

"In a world where [access to] private information can protect the taxpayer or stop a multitude of crimes or save lives, in my view there can ultimately be no absolute right to privacy," he said.

"There should be many constraints to intruding on that privacy, but what there has to be and what there has been in the past is the sense of shared responsibility between service providers and governments to protect both privacy and security as best they can."

Hague, who was foreign secretary between 2010 and 2014, acknowledged a lingering "deep suspicion" of both the government and intelligence agencies, such as GCHQ and MI5, but said this was simply "a sign of a free society."

Yet the need for intelligence, from the perspective of these agencies, is more important than ever, he argued.

"If we were not able to gather intelligence effectively about organised crime or terrorist activity, restrictions on the liberty of our citizens in many other ways would have to be much more serious and Draconian," Hague asserted.

"We are able to leave most people undisturbed by law enforcement activities because they can be focused on the people who are most likely to be a problem for the country."

He added: "[When foreign secretary] on a daily basis I saw the need for intelligence to frustrate organised crime and terrorism and foreign espionage. Its a depressing fact there are far more organisations [...] than the average citizen might suspect exist, who would like to cause people in this country harm. A huge proportion of the work that we do to detect that is electronic in some way."

He went on to list a number of groups the intelligence agencies routinely combat through bulk data collection and surveillance – including sex traffickers, drug dealers and terror groups. He said it was inevitable this work would "involve some invasion of privacy."

He said: It's bound to involve the state being able, in exceptional circumstances, to look into the private communications of the people we believe might be involved in some of [these] activities.

In the UK, the Investigatory Powers Bill, also referred to as the Snoopers' Charter by critics, is passing through parliament. The law will effectively legitimise a number of surveillance techniques intelligence agencies have used for years – including bulk data collection and interception. On 7 June, it passed in the House of Commons with 444 votes to 69.

According to Hague, such an "overhaul" of UK surveillance law was long overdue however he appeared to take offence at the derogatory names it is sometimes branded by opponents.

"People don't often hear what its like to actually make these decisions about intercepting communications. If people could see it in action they would see how ridiculous the idea of a Snoopers' Charter is," he said.

Big data vs mass surveillance

The former foreign secretary also maintained the law does not provide intelligence agencies with backing to conduct mass surveillance. Instead, Hague said the distinction must be made between this and 'big data' collection.

"Clearly, there is a need in government and intelligence for big data," he said. "But that is different from what people are saying [about] their communications being under surveillance, being intercepted, being read, that is a different thing. Big data is different from mass surveillance and we do have to distinguish these things."

Yet as previously reported, the operations of agencies like GCHQ and MI5 are sometimes highly invasive – from the collection of so-called bulk personal datasets to the bending of rules to keep oversight to a minimum.

During his keynote, Hague was confronted by one such headline in relation to the Snowden revelations about a GCHQ programme called 'Optic Nerve' that was reportedly scooping up private webcam images belonging to 1.8 million people using via a Yahoo application.

Nonplussed, Hague replied: "I cant go into specific things but I would say: don't always believe what you read in The Guardian. You would have a pretty distorted view of the world."

He continued: "The interception of the contents of the communication of an individual in the UK can only be done with a warrant signed by the secretary of state. So, I think that can be of some reassurance. The [Investigatory Powers Bill] will have even more checks and balances. Hopefully that is some reassurance to readers of the Guardian."

It does raise an interesting point: does this mean the secretary of state warranted the use of Optic Nerve at the time?

In his speech, Hague did not hide his distain for Edward Snowden, who in 2013 leaked a trove of data that exposed the spying apparatus used by both UK and US intelligence outfits. "The Snowden affair led many people to change their behaviour in ways that have led to reinforced privacy for criminal activity," he claimed.

Looking to the future, Hague predicted a rise in 'cyber offensive' activity. "Countries that cant defend their citizens, their armed forces, their companies against intrusion or manipulation will be overtaken by other countries. [Cyber] will become a critical, national advantage or disadvantage," he said.

He continued: "For countries or companies that don't successfully protect themselves, identities will be stolen, intellectual property will be taken by others, warplanes will be outmanoeuvred.

"Airspace will be invaded, financial institutions will be embarrassed, private information will be published, security agencies will be infiltrated, infrastructure will be made vulnerable and so for the individual, for the company, for the government or nation – there is a need for both privacy and security.

"We have to adapt," he warned.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.