World Alzheimer's Day 2015: Liraglutide clinical trial on verge of being blockbuster cure for disease

A diabetes drug that appears to stop the progression of Alzheimer's is showing promising results in the first human clinical trial. Liraglutide has previously been shown to be effective at restoring memories and protecting the brain from the disease in mice – and scientists are hopeful it could result in a cure in as little as five years.

Christian Hölscher, from Lancaster University led the previous studies testing the effects of liraglutide on mice and is now part of a human trial on early-state Alzheimer's patients. Speaking to IBTimes UK ahead of World Alzheimer's Day, he said the team is currently carrying out research in the Hammersmith in London and the Addenbrooke hospital in Cambridge. Another pilot study has also been carried out in Denmark and results showed the drug protects the brain from Alzheimer's and prevents deterioration.

"They could show the drug gets into the brain and protects it from deterioration," he said. "In one cognitive test they also found the group that didn't get the drug were getting worse while the drug group didn't get worse at all. It's a small study, but it's very exciting because it's genuine data on human subjects which show there's something there and that something is happening. We just have to find out how much and for how long you need to treat these people. These are exciting times.

How liraglutide works

Liraglutide is currently used to treat type 2 diabetes. A link between this disease and Alzheimer's was discovered several years ago, with research showing people with diabetes are more likely to develop Alzheimer's than healthy people in the same age group. Lirglitude is used to stimulate insulin production in diabetes. This reduces the amount of sugar in the blood and helps to slow digestion.

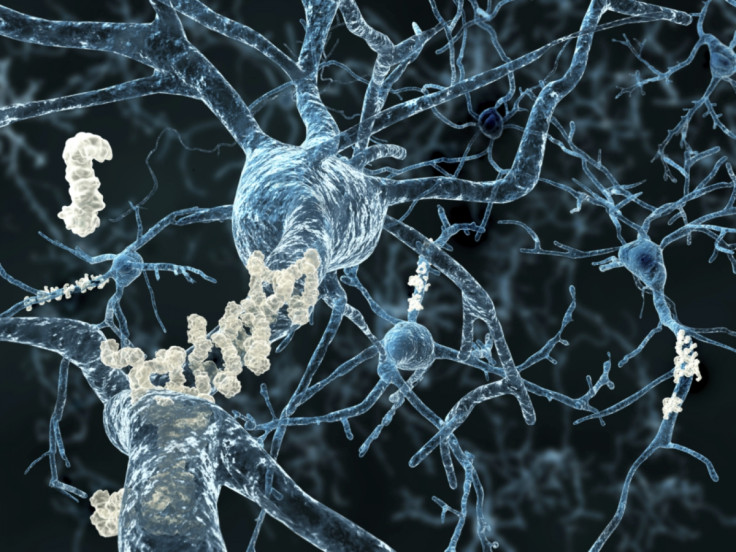

However, insulin also stimulates growth and repair of nerve cells. An insulin-like protein (GLP-1) had previously been shown to reduce the production of amyloid-beta protein that forms in the brain of Alzheimer's patients. While GLP-1 cannot be used as a treatment because it is broken down by the body so fast, other drugs – like liraglutide – mimics its effects.

Liraglutide can also pass through the blood brain barrier, which stops toxins (including drug therapies) from entering the brain. In studies on mice, scientists found the drug improved symptoms of the disease and reduces the amount of amyloid plaques in the brain – a hallmark of the disease. In mice, memories were improved and they were better able to recognise objects.

Hölscher said he was astonished at the results: "We got the first result I was surprised I didn't expect that to happen, I wasn't sure if the students who did the work did the work properly, so we did it again and got other people to repeat the study and since then a lot of other labs have repeated and done similar work and could show the same effect. So it is a genuinely powerful drug, the question is will it work in the same way in humans as it does in animals. That's always the big question."

Phase 2b trial

Following the positive results in the mice trial, researchers set about carrying out a study on humans – which they are currently about half way through. Because liraglitude is already approved for use on diabetic patients, and has been for many years, it is perfectly safe for humans – making it an obvious choice to trial.

There already is a lot of interest – people and research from different companies that are curious about what's going on here, it's clearly a hot subject. But if we get the positive results from phase 2 it will be a blockbuster

They hope to have results from the trial at the end of next year, but currently need more participants to test the drug on: "Unfortunately the recruitment process is a bit slow – slower than we anticipated, but the whole thing is ongoing and we will get it finished," Hölscher said.

"There are already patients receiving the drug and they are in the early developmental phase of Alzheimer's disease. They receive the drug or a placebo and nobody knows who gets what. They will receive the drug for one year and there will be brain scans and blood samples to look at biomarkers. And of course cognitive tests to see if they have deteriorated or not."

Early-stage Alzheimer's patients were chosen in order to have the best chance of having an effect. The trial is designed to show that the drug has an effect and that it modifies the disease. If they are able to show this, they will be able to move to a phase 3 trial.

Alzheimer's treatments and the search for a cure

There have been no new treatments for Alzheimer's for over a decade and current therapies only alleviate symptoms or slow progression. "There hasn't really been anything for a very long time. Most of the trials didn't really produce anything, they seem to have bene looking at the wrong biomarkers and mechanisms," Hölscher said. Previously, scientists had tested insulin – another obvious choice – but this has to be administered to a nasal spray and is not idea for people who do not have diabetes.

With that in mind, they decided to try liraglutide. "This would definitely be a blockbuster because there hasn't been anything worth mentioning in the past," he said. "Fortunately the first data we have from human brain tissue and the first clinical trial, it really shows that yes, the drug gets into the brain and is protective – and seems to work in a similar way it does in animals. That's hugely encouraging.

"We hope this is the cure. Obviously in humans we don't have a lot of data, but the data we have shows it stops disease progression. So we are hopeful it will stop the disease and that would be the answer – the cure so to speak."

Once they have the results, they will then run a phase 3 trial, at which point different companies are expected to come on board, meaning funding and patient participation is easier. This means the process can be done fairly quickly. FDA approval should also be fairly straightforward because liraglutide is already approved for diabetes: "So this would just be an extension, proving it for further use in Alzheimer's and of course you have to demonstrate that it is effective first," he explained

"We're waiting for the trial to finish and are eagerly awaiting the results. And then hoping the whole thing will take off. There should be so much excitement and there already is a lot of interest – people and research from different companies that are curious about what's going on here, it's clearly a hot subject. But if we get the positive results from phase 2 it will be a blockbuster."

The clinical trial is led by consultant physician Dr Paul Edison of Imperial College, London. Volunteers can contact the recruitment office at 020 8383 3704 or 020 8383 1969 or by email at memory@imperial.ac.uk

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.