World Malaria Day 2015: 5 scientific breakthroughs in fighting the disease

Around half of the world's population are at risk of malaria. More than half a million lives are still lost to the disease every year and at least three quarters of malaria deaths occur in children under the age of five. In 2013, only one in five African children with malaria received effective treatment, 15 million pregnant women did not receive a single dose of preventative drugs and an estimated 278 million in Africa still live in households with no insecticide-treated bed net.

Despite this, steps have been taken to increase prevention and control measures in countries where malaria is endemic. Since 2000, mortality rates have dropped by 47% globally; once widespread across five continents, malaria is now in 99 countries. In recent years, dedicated research has led to breakthroughs in quicker diagnoses, vaccines and natural immunity. On World Malaria Day, on 25 April, IBTimes UK looks at some of the major advances in beating the disease.

Breath test

Australian scientists announced breath testing may lead to an easier and earlier detection of malaria, in a groundbreaking study that may eventually replace the traditional blood test. Researchers at the CSIRO and QIMR Berghofer Medical Research Institute discovered people infected with malaria had higher levels of a sulphur-based chemical on their breath.

The chemicals cannot be detected by the human nose but increase with the severity of the disease. Professor James McCarthy, of QIMR Berghofer, told IBTimes UK researchers are working to develop cheap biosensors that can be used in clinics in the field, to detect malaria.

"Quicker diagnosis would not only save lives but could also help reduce the spread of malaria because people can help transmit the infection before the symptoms become evident," McCarthy said. "A breath test would also be less invasive than the current blood test, and this would make a big difference because many of those affected by malaria are children in developing countries."

World's most advanced malaria vaccine

The world's first viable vaccine against the disease could be available in African countries as early as October, after final trial results confirmed its potential to partially prevent malaria in children. Researchers said the vaccine, called RTS,S, was effective in more than a third of children when the first dose is administered between the ages of five and 17 months.

"Given that there were an estimated 198 million malaria cases in 2013, this level of efficacy potentially translates into millions of cases of malaria in children being prevented," the researchers said. If the vaccine is approved, it will be the first licensed vaccine against malaria anywhere in the world.

Gut bacteria

Researchers at the Instituto Gulbenkian de Ciência in Portugal announced in December 2014 that friendly bacteria in the human gut can trigger a natural immune response against malaria. The sugary proteins on the surface of some healthy gut bacteria teach the immune system to fend off the parasite responsible for the disease, which may explain why some people appear to be naturally immune to malaria.

A vaccine containing the sugar, known as alpha-gal, may work in humans. "One of the beauties of the protective mechanism we just discovered is that it can be induced via a standard vaccination protocol, leading to the production of high levels of anti-alpha-gal antibodies that bind and kill the Plasmodium parasite," lead researcher Miguel Soares said. "If we can vaccinate these young children against alpha-gal, many lives might be saved."

Genetically modified mosquitoes

Creating mosquitoes that produce 95% male offspring by using a sex-distorting genetic defect may help control malaria, scientists found in 2014. Malaria is caused by a parasite called a Plasmodium and is spread by female Anopheles mosquitoes, who pick up the parasite from infected people when they bite to obtain the blood needed to nurture their eggs.

An important step forward in a genetic control strategy, it works by shredding the X chromosome during sperm production – leaving behind the few X-carrying sperm to produce female embryos. When the cages of normal mosquitoes were infested with the new strain, it caused a shortage of females and a population crash – cutting the number of mosquitoes able to spread the disease.

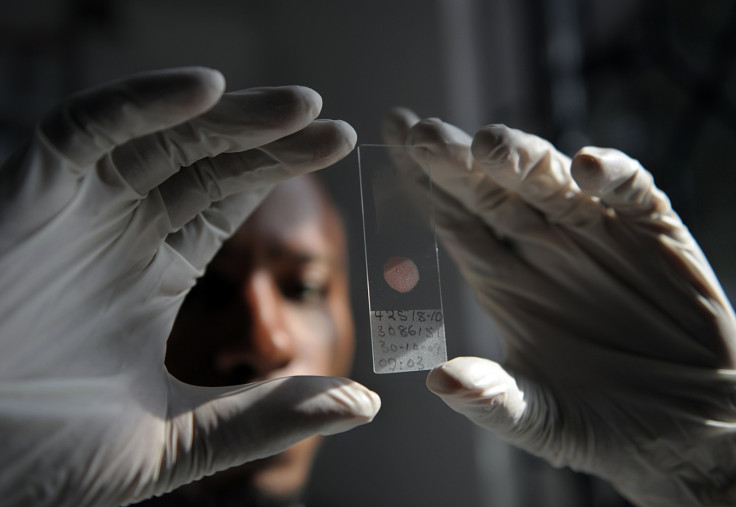

Anti-malaria drugs

As drug-resistant malaria continues to pose a threat, Australian scientists have made headway in the race to find new drugs to fight the disease. Publishing their research in the scientific journal Nature, researchers were able to block the export of important proteins in red blood cells which are essential to sustaining the malaria parasite. It is a revelation in the process of creating new drugs – as there is only one drug left, artemisinin, to treat the disease.

"This is a major advance in the quest for new malaria drugs," said co-author Professor Brendan Crabb. "If we can discover a drug that blocks the protein complex that comprises this gateway, you can effectively block the functioning of several hundred proteins."

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.