America's opioid crisis: How the strength of prescription drugs created a public health emergency

KEY POINTS

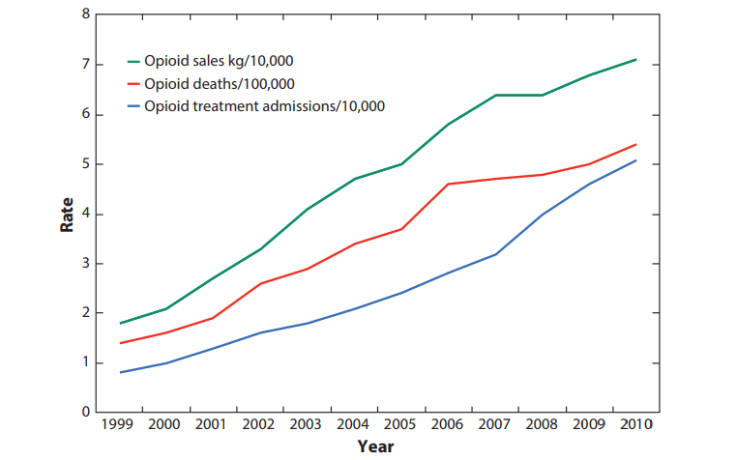

- Between 1999 to 2015 over 183,000 people died from overdoses related to opioids.

- Donald Trump recently declared the opiate crisis in the US a public health emergency.

In the US, around 100 people every day die of an opioid overdose. The country is now in the depths of a tragic opioid crisis.

In late October, President Donald Trump described the situation as a "national shame", declaring a public health emergency and pledging to "mobilise his entire administration" to tackle the epidemic. What that entails remains to be seen.

But what is clear is the US must overcome the emergency quickly, or else risk losing the lives of an further 650,000 people. Those figures are according to estimates by the health website Stat. The epidemic has killed over 183,000 people between 1999 and 2015. In 2016 alone, drugs killed 64,000 people – mainly through synthetic opioids, heroin, and painkillers. That tops the death toll of the Vietnam War and both Iraq wars – combined.

The catalyst for all this was a shift in the way that pain is managed, Dr Jay C Butler, chief medical officer for the Alaska Department of Health and Social Services, tells IBTimes UK.

Both patients and healthcare providers saw opioids as a safe and effective way of eliminating acute and chronic pain. This included medicines such as Percocet and OxyContic.

Doctors moved quickly to handing out the stronger medications. This was combined with an apparent lack of awareness of the dangers of addiction and alternative behavioural strategies for managing chronic pain, according to Dr Paul McLaren, consultant psychiatrist and an addiction expert at the Priory's Hayes Grove Hospital in Kent.

"This belief was fostered through aggressive marketing more than good science," adds Dr Butler.

"This came at the same time as greater accessibility to internet-based sources that did not require prescriptions. It is probably the case that the web contributed to the problem," Dr McLaren tells IBTimse UK.

"No part of the country has been spared," says Dr Butler. "However, New England and Appalachia have been hardest hit for the longest period of time. Even in my state of Alaska, we have had overdose deaths in the most remote villages, hundreds of kilometres from the nearest road."

Opioids are so addictive because they push the buttons of the brain usually triggered by pleasurable activities, like eating, but in a more powerful way. This prompts the body to release the chemical dopamine, which encourages more use. In turn, the body becomes reliant on the substance, and a person will experience extreme withdrawals without it. Cravings for the drug can last long after a user stops, making it easy to relapse.

The acceptability of opioids led to a dramatic increase in the number of people who became physically dependent.

The strength of prescription drugs has contributed to the death count in two major ways. Firstly, higher strength preparations can be cut into a greater number of doses. Secondly, higher dose preparations, such as the 80mg OxyContin, may be used by someone for whom the drug was not prescribed, either for pain relief or for the high. These users may not realising that the dose can be deadly for someone who has not been using opioids long-term.

"There are anecdotal reports of persons who have died of overdose after taking a single pill of one of these high dose preparations," says Dr Butler.

"As addiction took its toll, more people lost jobs, lost insurance coverage, and lost the relationships with their regular providers, creating a large, inelastic market for opioids."

A flood of relatively cheap heroin, mainly from Mexico, has plugged this gap over the last decade. In the past three years, the needs of desperate addicts were also met by the importation of illicit fentanyl and related compounds, adds Dr Butler. Even cheaper than heroin to produce and of a high potency, these drugs are readily available for purchase in large quantities over the internet.

"The influx of fentanyl has been a particularly deadly phenomenon in that it is a more powerful opioid and because many users do not realise that they are using fentanyl," explains Dr Butler. "Fentanyl is often mixed with heroin and sold as such, or pressed into counterfeit pills that look like prescription opioid presentations.

"Thus, a user may think that they are crushing, mixing, and injecting an oxycodone tablet when in fact they are injecting the much more powerful fentanyl. Using illicit drugs is a game of Russian roulette. Fentanyl has put more bullets in the chambers."

In 2016, the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has responded by publishing guidelines advising against the use of prescription painkillers for common conditions, and pointing patients towards non-addictive medications such as ibuprofen.

Shifts can also be seen in how law enforcement agencies arrest dealers and suppliers rather than criminalising users.

However, if the US is to tackle the the opioid crisis, attitudes towards drugs but also addiction must change, stresses Dr Butler. Addicts must not be dismissed as having a "bad habit" or "moral failing".

"The most important thing for the US public, including medical providers, is to understand is that addiction is a chronic health condition of the brain. Our approaches needs to be more akin to how we address other chronic conditions, such as diabetes, hypertension, or asthma," he says.

As such, access to naxalone to treat oversdoses and long-term therapies that help people into recovery are vital.

The US would be wise to look to Iceland, he adds, where teen smoking, drinking and drug use have plummeted in the past two decades as access to elicit substances have been restricted and money has been invested in organised sport, music, art, dance, and other pursuits. However, the US is in too deep for that alone to fix its problems.

James Hodge, professor at the Sandra Day O'Connor College of Law at Arizona State University, comments that while it is positive that Trump has declared a public health emergency, a national emergency would free up more resources for the cause. He predicts this may soon happen.

"While a Public Health Emergency Declaration is meaningful, it does not carry the imprimatur of a federal-wide response that only a national emergency can authorise," he says.

"The opioid crisis is a complex disaster; as such, the response needs to be comprehensive, multi-tiered and multi-sectoral. There will be no quick, easy solutions," says Dr Butler.

"We have to have a comprehensive approach that is not molecule-specific; otherwise, we will only continue to have the ongoing rotation of misuse, addiction and death caused by the latest drug fad."

Attitudes are changing, but sadly because so many lives have been destroyed by the epidemic, he adds.

"Opioid addiction is increasingly being recognised as 'our problem' rather than a problem of 'those people'."