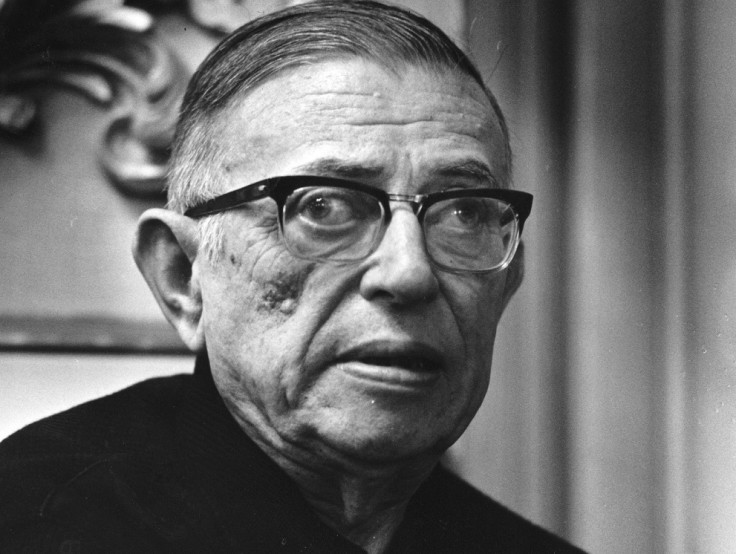

Nobel Prize in Literature: Why Jean-Paul Sartre Refused the Controversial Award in 1964

The literary Nobel Prize has had a history steeped in controversy since it was first awarded in 1901. But perhaps no other year has been more interesting than 1964, when Jean-Paul Sartre discovered he was among the writers being considered for the laureate.

A French playwright, novelist, screenwriter, literary critic and political activist, Sartre was one of the leading figures in French philosophy of the 20<sup>th century, and the driving force behind the school of reasoning known as existentialism. When rumours began circulating that he was in the running for the prize, Sartre immediately wrote to the Swedish Academy to inform them he wanted to be withdrawn from consideration.

Unaware that no consultation made between the academy and nominees, Sartre was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature for his work "rich in ideas and filled with the spirit of freedom and the quest for truth". He refused it, citing both personal and objective reasons in a statement made to the Swedish Press on 22 October.

But why did Sartre refuse the literary Nobel?

Personal

Assuring the press that his decision was not an "impulsive gesture", one of the reasons Sartre gave for rejecting the prize stemmed from his habit of refusing all official honours. In 1939, Sartre was drafted into the French army where he served as a meteorologist, before being captured by German trooped in Padoux in 1940. He spent nine months as a prisoner of war, and in 1945, he was offered the Legion of Honour – and refused it.

Sartre believed every individual is responsible for creating a purpose for their life. By accepting the prize, Sartre would inadvertently associate himself with the institution that honoured him.

His humble conception of the writer's "enterprise" – as he called it in his explanation – led Sartre to believe that those in political, social or literary positions should only "act with the means that are his own – the written word".

"The writer must therefore refuse to let himself be transformed into an institution, even if this occurs under the most honourable circumstances, as in the present case," he said. "This attitude is of course entirely my own, and contains no criticism of those who have already been awarded the prize."

It is evident that he wanted to accept no award that would add weight to his name. "If I sign myself Jean-Paul Sartre it is not the same thing as if I sign myself Jean-Paul Sartre, Nobel Prizewinner," he said.

Beyond disputes over which contributor's work was worthier, countless other authors have criticised or dismissed the prize for personal reasons. Haruki Murakami, one of the writers tipped to win this year's prize and a long-term favourite, previously laughed off the possibility of winning the coveted award saying he didn't want prizes – as "that means you're finished".

Cold War politics and objectives

After the Second World War, the second period of Sartre's career involved highly publicised political involvement – when the world was split into communist and capitalist blocks. Sartre embraced Marxism but did not join the Communist Party. As one of the first French journalists to expose the use of Siberian labour camps, he attacked what he saw as abuses of freedom and human rights by the Soviet Union.

Sartre cited his conflicted loyalties between the East and the West as another reason why he declined the Nobel. Although sympathetic to socialism and the Eastern bloc, he had been brought up in a Western "bourgeois family" - and accepting the award would inevitably mean he had been "institutionalised in either East or West".

At the time, Sartre said he regarded the prize as a "distinction reserved for the writers of the West or the rebels of the East".

"This is why I cannot accept an honour awarded by cultural authorities, those of the West any more than those of the East, even if I am sympathetic to their existence. Although all my sympathies are on the socialist side. I should thus be quite as unable to accept, for example, the Lenin Prize, if someone wanted to give it to me, which is not the case."

Controversies

Although Sartre openly said he regretted the incident had become a "scandal" – the writer was not the first, and certainly was not the last, to snub the prize for political reasons.

Argentinian writer Jorge Luis Borges was nominated several times, but never won the prize. Some observed that Borges was omitted because of his conservative political views – specifically, because he had accepted an honour from Chilean dictatorship Augusto Pinochet.

Borges' failure to win the prize contrasts significantly with writers who openly supported left-wing dictatorships – as was the case with Sartre.

Between 1901 and 1912, Sweden's antipathy towards Russia was cited as the reason neither Tolstoy nor Anton Chekov were awarded the prize. During the Second World War, the Academy favoured writers from non-combatant countries.

The heavy focus on European authors has been a subject of mounting criticism, as the majority of laureates have been European. In 2008, Horace Engdahl, the former secretary of the Academy claimed that Europe was still the "centre of the literary world".

"The US is too isolated, too insular," he said. "They don't translate enough and don't really participate in the big dialogue of literature."

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.