The truth about Easter Island: A sustainable society falsely blamed for its own demise

New research is painting a different picture of the fate of the island and its inhabitants.

Few places on Earth are as well known for their so-called mysteries as Easter Island, also known as Rapa Nui. For a tiny island of 64 square miles, with its nearest neighbours some 1,300 miles away, it has seen more than its fair share of controversy.

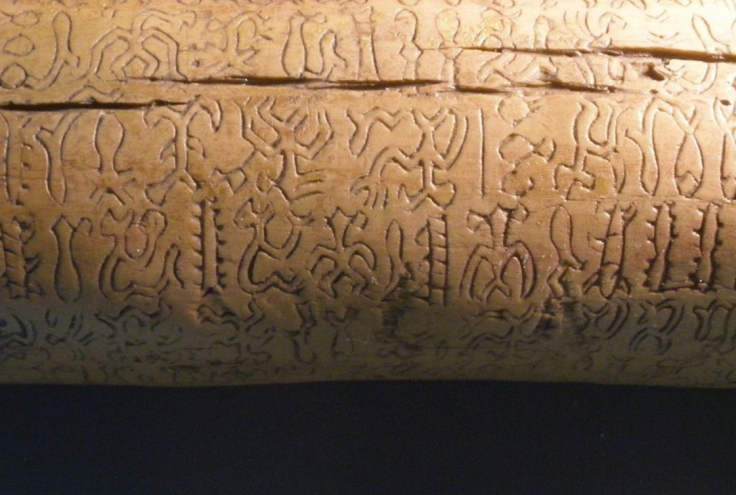

For a long while it wasn't clear whether the island's native population originated in Polynesia or South America. And how can we explain its apparent paradox: the design, construction and transport of giant "moai" stone statues, a remarkable cultural achievement yet one carried out on a virtually barren island, which seemingly lacked both the resources and people to carry out such a feat?

Anthropologists have long wondered whether these seemingly simple inhabitants really had the capacity for such cultural complexity. Or was a more advanced population, perhaps from the Americas, actually responsible – one that subsequently wiped out all the natural resources the island once had?

Recently, Rapa Nui has become the ultimate parable for humankind's selfishness; a moral tale of the dangers of environmental destruction. In the "ecocide" hypothesis popularised by the geographer Jared Diamond, Rapa Nui is used as a demonstration of how society is doomed to collapse if we do not sit up and take note. But more than 60 years of archaeological research actually paints a very different picture – and now new genetic data sheds further light on the island's fate. It is time to demystify Rapa Nui.

The 'ecocide' narrative doesn't stand up

The ecocide hypothesis centres on two major claims. First, that the island's population was reduced from several tens of thousands in its heyday, to a diminutive 1,500-3,000 when Europeans first arrived in the early 18th century.

Second, that the palm trees that once covered the island were callously cut down by the Rapa Nui population to move statues. With no trees to anchor the soil, fertile land eroded away resulting in poor crop yields, while a lack of wood meant islanders couldn't build canoes to access fish or move statues. This led to internecine warfare and, ultimately, cannibalism.

The question of population size is one we still cannot convincingly answer. Most archaeologists agree on estimates somewhere between 4,000 and 9,000 people, although a recent study looked at likely agricultural yields and suggested the island could have supported up to 15,000.

But there is no real evidence of a population decline prior to the first European contact in 1722. Ethnographic reports from the early 20th century provide oral histories of warfare between competing island groups. The anthropologist Thor Heyerdahl – most famous for crossing the Pacific in a traditional Inca boat – took these reports as evidence for a huge civil war that culminated in a battle of 1680, where the majority of one of the island's tribes was killed. Obsidian flakes or "mata'a" littering the island have been interpreted as weapon fragments testifying to this violence.

However, recent research lead by Carl Lipo has shown that these were more likely domestic tools or implements used for ritual tasks. Surprisingly few of the human remains from the island show actual evidence of injury, just 2.5%, and most of those showed evidence of healing, meaning that attacks were not fatal. Crucially, there is no evidence, beyond historical word-of-mouth, of cannibalism. It's debatable whether 20th century tales can really be considered reliable sources for 17th-century conflicts.

What really happened to the trees

More recently, a picture has emerged of a prehistoric population that was both successful and lived sustainably on the island up until European contact. It is generally agreed that Rapa Nui, once covered in large palm trees, was rapidly deforested soon after its initial colonisation around 1200 AD. Although micro-botanical evidence, such as pollen analysis, suggests the palm forest disappeared quickly, the human population may only have been partially to blame.

The earliest Polynesian colonisers brought with them another culprit, namely the Polynesian rat. It seems likely that rats ate both palm nuts and sapling trees, preventing the forests from growing back. But despite this deforestation, my own research on the diet of the prehistoric Rapanui found they consumed more seafood and were more sophisticated and adaptable farmers than previously thought.

Blame slavers – not lumberjacks

So what – if anything – happened to the native population for its numbers to dwindle and for statue carving to end? And what caused the reports of warfare and conflict in the early 20th century?

The real answer is more sinister. Throughout the 19th century, South American slave raids took away as much as half of the native population. By 1877, the Rapanui numbered just 111. Introduced disease, destruction of property and enforced migration by European traders further decimated the natives and lead to increased conflict among those remaining. Perhaps this, instead, was the warfare the ethnohistorical accounts refer to and what ultimately stopped the statue carving.

It had been thought that South Americans made contact with Rapa Nui centuries before the Europeans, as their DNA can be detected in modern native inhabitants. I have been involved in a new study, however, led by paleogeneticist Lars Fehren-Schmitz, which questions this timeline. We analysed Rapanui human remains dating to before and after European contact. Our work, published in the journal Current Biology, found no significant gene flow between South America and Easter Island before 1722. Instead, the considerable recent disruption to the island's population may have impacted on modern DNA.

Perhaps, then, the takeaway from Rapa Nui should not be a story of ecocide and a Malthusian population collapse. Instead, it should be a lesson in how sparse evidence, a fixation with "mysteries", and a collective amnesia for historic atrocities caused a sustainable and surprisingly well-adapted population to be falsely blamed for their own demise.

And those statues? We know how they moved them; the local population knew all along. They walked – all we needed to do was ask.

Catrine Jarman, PhD researcher in Archaeology and Anthropology, University of Bristol

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.