What is the amygdala? Stimulating the brain with electricity can improve memory

Deep brain stimulation could be used to treat certain neurological disorders, according to researchers.

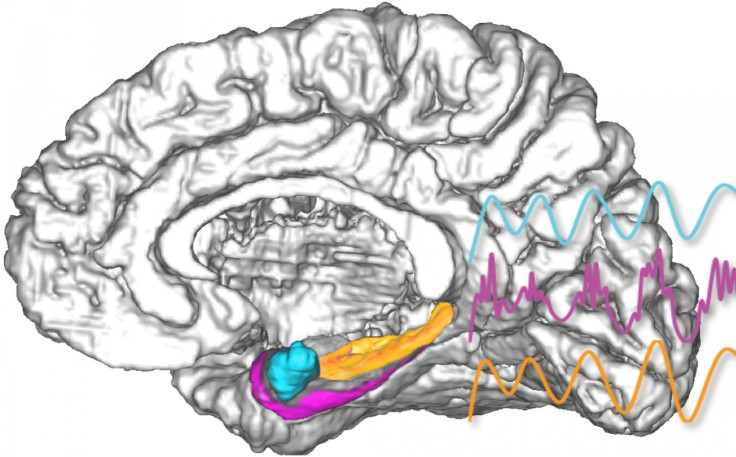

Neuroscientists have found a way to improve human memory by directly stimulating a region of the brain known as the amygdala, according to a new study published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

The findings are the first example of electrical brain stimulation in humans having a positive effect on memory lasting for more than a few minutes, researchers from Emory University say.

The study involved 14 epilepsy patients who were undergoing an invasive procedure which involves electrodes being introduced into the amygdala – a brain region that is responsible for regulating memory and emotional behaviours.

Using the electrodes, scientists performed deep brain stimulation (DBS) on the patients to manipulate specific brain circuits in the amygdala. DBS is currently an established clinical method for the treatment of disorders such as Parkinson's and is being investigated for its efficacy in treating depression.

Participants viewed 160 objects on a screen and were asked to judge whether they belonged indoors or outdoors. For half of the images, the participants received electrical stimulation for one second after each image disappeared. They were subsequently tested by the researchers on their recognition of the images both immediately after viewing them, as well as the next day.

The team found that 11 out of the 14 participants showed an improvement in overnight memory tests with the increase in the number of images accurately recognised ranging from 8% to several hundred percent when compared to tests taken without any electrical stimulation.

"This makes sense because the amygdala is thought to be important for memory consolidation - making sure important events stick over time," said co-author Joseph Manns.

Patients with poor memory witnessed a greater improvement when recognising the stimulated images. For example, one patient forgot all of the control images - for which they received no stimulation, but maintained good memory for the images where they did receive stimulation.

A more substantial effect was seen in people who had an average memory to start with.

"The average was like having a 'B'-level memory performance move up to an 'A'," said Jon T. Willie, senior author of the study.

In future, techniques such as the one outlined in the study could be used to treat certain neurological disorders.

"One day, this could be incorporated into a device aimed at helping patients with severe memory impairments, like those with traumatic brain injuries or mild cognitive impairment associated with various neurodegenerative diseases," said co-first author Cory Inman. "However, right now, this is more of a scientific finding than a therapeutic one."