3.5 billion year-old fossils are the oldest ever evidence of life on Earth

Researchers say the findings indicate that life could be fairly common throughout the Universe.

Microscopic fossils discovered in a 3.5-billion-year-old piece of rock are the oldest fossils ever found and the earliest direct evidence of life on Earth, according to researchers.

A new study, published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, describes 11 microfossils which, the authors say, prove that life on Earth must have begun before 3.5-billion-years-ago. The fossils measure around 10 micrometers wide – eight times thinner than a human hair.

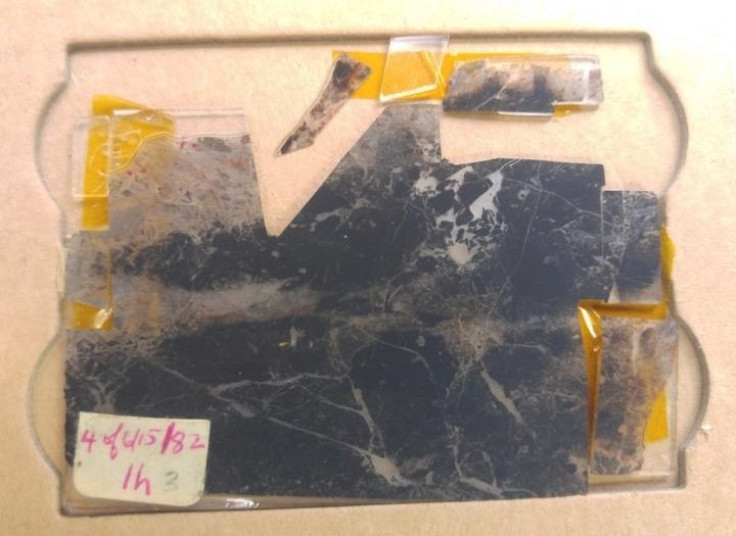

An initial study describing the fossils was published in 1993 in the journal Science by J. William Schopf - a paleobiologist from UCLA - and his team, eleven years after they were first discovered in the Apex Chert deposit in Western Australia. This region is one of the few places on the planet where geological evidence from the early part of Earth's history has been preserved.

Schopf's initial findings were disputed, however, with critics arguing that the purported biological specimens were simply odd-looking minerals.

But using an advanced piece of equipment known as a secondary ion mass spectrometer (SIMS), the researchers say they can confirm the biological origins of the find.

"I think it's settled," said John Valley, professor of geoscience at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, who co-led the study.

The findings show that the fossils represent a primitive but diverse group of organisms including phototrophic bacteria, which relied on the sun to produce energy, gammaproteobacteria, which consumed methane, and a group of microorganisms from the domain of life Archaea that produced methane.

Some of these organisms are now extinct, while others are very similar to microbial species that can still be found today.

The SIMS system had never been used before to analyse fossils this old and rare. In fact, it took Valley and his team nearly 10 years to refine the processes to the point where they were confident an accurate measurement could be made.

In fact, to prepare the fossils for SIMS analysis, the team had to painstakingly grind down and polish the original rock sample, one micrometer at a time, in order to expose the delicate fossils – which were encased in a hard layer of quartz – without damaging them.

The researchers say the findings of studies such as this indicate that life could be fairly common throughout the Universe.

And because the evidence suggests that several different types of microbes were present on Earth 3.5 billion years ago, "life had to have begun substantially earlier," said Schopf, adding that, "it is not difficult for primitive life to form and to evolve into more advanced microorganisms."

In previous studies, Valley and his colleagues have shown that liquid water oceans existed on Earth as early as 4.3 billion years ago, just 250 million years after the Earth formed.

"We have no direct evidence that life existed 4.3 billion years ago but there is no reason why it couldn't have," said Valley. "This is something we all would like to find out."

"People are really interested in when life on Earth first emerged," Valley said. "I think a lot more microfossil analyses will be made on samples of Earth and possibly from other planetary bodies."