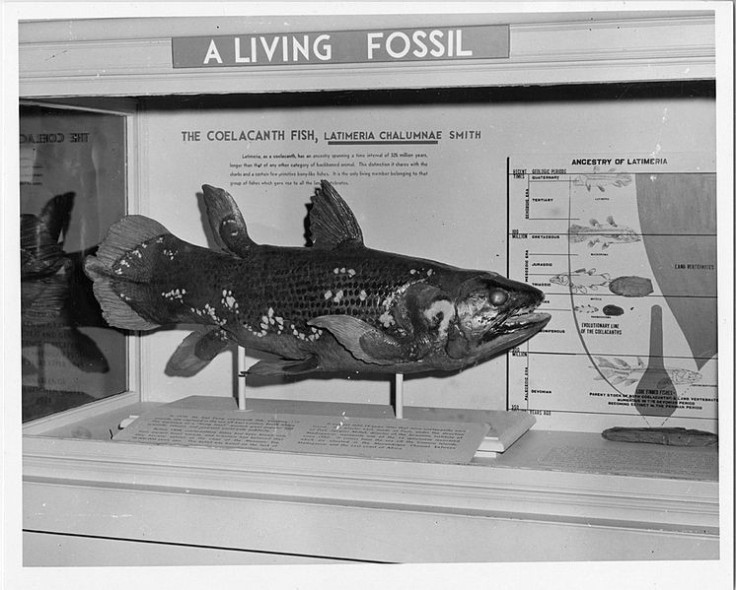

‘Living Fossil’ Coelacanth Frozen in Time for 300 Million Years

A type of fish known as a 'living fossil' has hardly changed biologically in around 300 million years.

The African coelacanth has effectively been frozen in time since before dinosaurs evolved.

Researchers at the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard have decoded the genome of the coelacanth to find it has evolved extremely slowly over the years and has hardly changed in comparison with its ancient fossilised skeletons.

Jessica Alfoldi, co-author of the study, which was published in the journal Nature, said: "We found that the genes overall are evolving significantly slower than in every other fish and land vertebrate that we looked at. This is the first time that we've had a big enough gene set to really see that."

The term living fossil was coined by Charles Darwin; however Alfoldi says this should not be attributed to the coelacanth: "It's not a living fossil; it's a living organism. It doesn't live in a time bubble; it lives in our world, which is why it's so fascinating to find out that its genes are evolving more slowly than ours."

Coelacanth live in sea caves and grow to about five foot long. They have limb-like fins and scientists thought they were extinct until one was discovered in 1938.

Researchers believe coelacanth evolve very slowly because they have no need to - its habitat in the ocean has changed very little in the last 300 million years.

Kerstin Lindblad-Toh, senior author of the paper, said: "Coelacanths are likely very specialised to such a specific, non-changing, extreme environment - it is ideally suited to the deep sea just the way it is."

The sequencing of the coelacanth genome has allowed scientists to discover more about the mysterious species, such as its lobed fins which look like four-legged land animals.

They found almost three billion letters of DNA and compared it to that of the lungfish, which also has lobed fins.

Researchers could then determine whether four legged-amphibious creatures were more likely to have evolved from lungfish or coelacanth - findings showed tetrapods are more closely related to lungfish.

However, they also found evidence that when animals moved from sea to land their sense of smell developed to detect airborne odours. Researchers also say the coelacanth DNA suggests land animals developed immunity as they encountered new pathogens.

Chris Amemiya, another co-author of the study, said: "This is just the beginning of many analyses on what the coelacanth can teach us about the emergence of land vertebrates, including humans, and, combined with modern empirical approaches, can lend insights into the mechanisms that have contributed to major evolutionary innovations."

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.