Glass Ceiling: Addressing the Boardroom Gender Gap [BLOG]

The issue of gender balance on UK boards has moved quickly up the business agenda following last year's publication of Lord Davies' Women on Boards report, which outlined the benefits that a mixed board brings in terms of skills and fresh perspectives, and recommended that a minimum of 25 percent of FTSE 100 board members should be female by 2015.

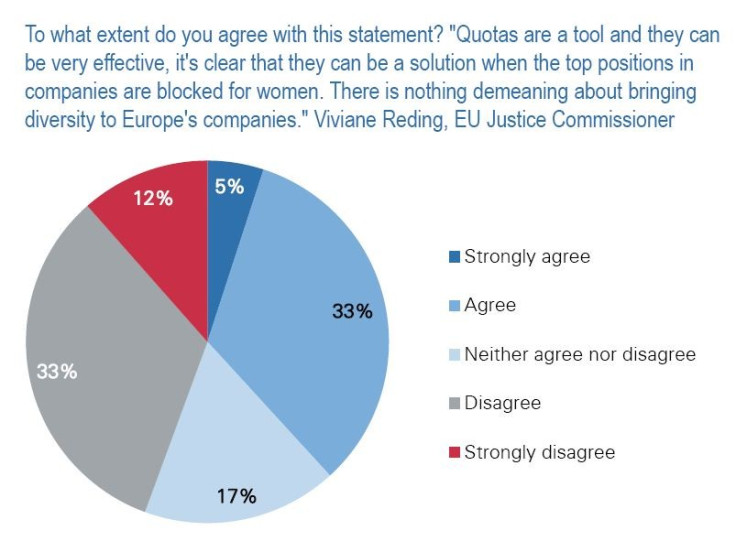

Across Europe the topic is also rising in importance, with a growing feeling that quotas may soon be imposed. When European Union (EU) justice commissioner Viviane Reding asked firms to pledge an increase of women on their boards to 30 percent by 2015 and 40 percent by 2020, only 24 firms responded to the invitation. A public consultation has now been launched to come up with a strategy for moving forward - and quotas have been highlighted as a potential tool to achieve change.

The good news is that in the ensuing 12 months since the Davies Report the proportion of women on the boards of FTSE 100 companies rose from 12.5 percent to 15.6 percent and there are now just 11 all-male boards remaining. Although the UK is still some way behind the front runners in Europe - Norway (40 percent), Sweden (25 percent) and France (22 percent) - it is comparable to others. Spain and the Netherlands are setting targets (30 percent), Italy and Belgium are considering legislation and Germany has its eye on quotas.

The Life Sciences perspective

How does the Life Sciences sector compare? To find out RSA commissioned the Women on Boards: A Life Sciences' Perspective study to find out what the situation is in the industry.

Does the gender imbalance mirror UK Plc and if so, what can be done to improve conditions? Is the Life Sciences industry a more favourable place for women to progress to the most senior positions and do senior managers believe more balanced boards bring a competitive edge?

These are some of the questions we researched in our study of 417 Board Directors and Senior Executives (75 percent of whom were director level). There was a fairly even split between male (57 percent) and female (43 percent) respondents. The boards of these companies ranged from just two people (16 percent) to 12+ (8 percent). Around a quarter (26 percent) had between three and five members and a third (31 percent) had between six and nine members. It is interesting to note a quarter of our sample had no female representation on the board.

Firstly, how does the UK Life Sciences compare to other sectors?

Given the high proportion of women in the industry, we would expect to see above average representation. However our research suggests that Life Sciences is probably no better (or worse) than other industries. Taking the Biosciences Industry Association (BIA membership) as an example, we find that 12 percent of its 348 registered board members are female. While at first glance this appears to be positive, on closer examination women board members are clustered in just a few firms.

A positive appetite for change

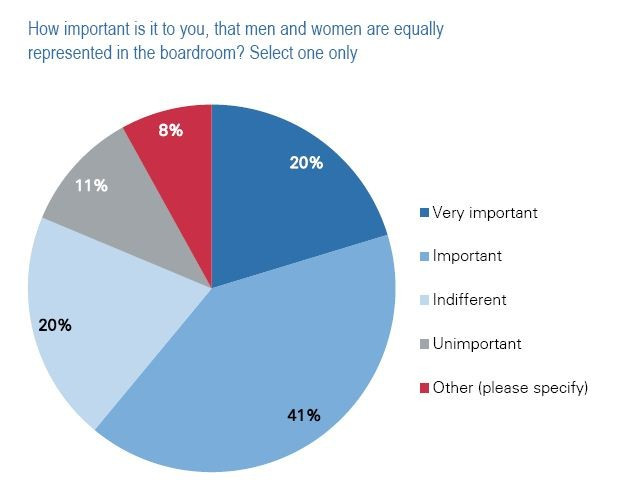

The good news is that our study found widespread agreement that balance and diversity make for better boards. Three fifths of those we surveyed stated that it is important that men and women are equally represented in the boardroom and that diversity is the key to creating the ideal senior management team. In fact some went further. Dr Melanie Lee, CEO of Syntaxin, believes that, "the boardroom should have a 50/50 split of women and men - then you get the very best of the particular strengths of male and female behaviours."

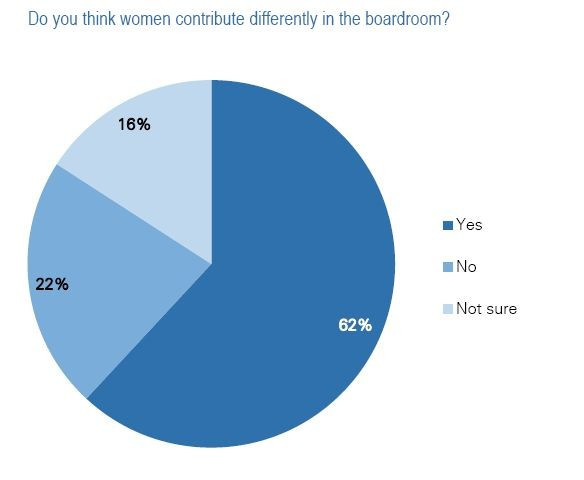

A clear majority (62 percent) of those surveyed recognised that women possess specific, vital skills and provide a different and valuable contribution. For example three quarters (75 percent) of managers rated women higher than men for intuition (people awareness and focus) and empathy (insight into how decisions play out in the wider organisation).

So there's widespread agreement that more balanced boards are good for companies in particular and the industry in general. What is holding diversity back? The survey highlighted three major barriers to change: 'the different work-life choices facing women', 'the dominant male culture of the boardroom' and 'the number of qualified female executives in functions represented on the board'. When asked to pick which of these barriers alone was most important 'dominant male culture' was cited by 32 percent of those we surveyed.

How can the imbalance be solved?

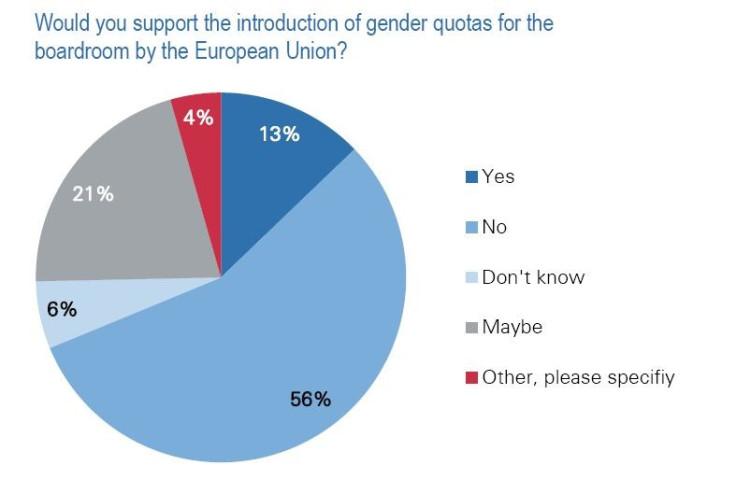

Most people didn't see quotas as the way forward, with only 13 percent supporting their use by the European Union or the British government. However, there is a hidden warning in the research results. When we drilled down into the responses by gender, we found that support for quotas was greater amongst women. A third of women were 'undecided' on the issue, as illustrated by this anonymous contributor: 'Quotas are not the best solution but they can be a solution if companies persistently fail to demonstrate a proportional representation of women in the senior positions.' Clearly the threat of quotas is the wake-up call that companies need to heed before it is too late.

The lack of female board members isn't down to a lack of talent. As Dr Ursula Ney, CEO of Genkyotex put it succinctly "Create an environment that is more conducive to women being involved. It's not that there aren't enough women in Life Sciences."

Asked what the industry could do to achieve a better balance in the boardroom, almost half highlighted factors such as more flexible working, proactive mentoring, greater transparency in recruiting and commitment and endorsement by business leadership as vital.

However, looking at these factors there is a marked difference between the sexes. While over half of men suggested more flexible working as the number one solution, this was only ranked fourth by women. Instead nearly two thirds (65 percent) of female contributors saw proactive mentoring as the key way of increasing female board membership. Essentially this demonstrates the need to consult with female executives, understand their concerns and act on them, rather than relying on first instincts.

Three key recommendations

The senior executives interviewed for the study had some quite specific recommendations for improving balance. Our panel of senior executives identified three key areas where the Life Sciences industry could be doing better:

1. Firstly, promote a more empathic business culture and working environment. Organisations need to show greater empathy and intuition around decision-making and communications to ensure that the right messages are getting through. There is a need to further break down any remaining institutional chauvinism and provide a more flexible working environment where presentation time in the office is not necessarily a requirement.

2. Undertake appropriate and sustained learning and development. The industry needs to be planning and investing well ahead. The aim should be to develop the board leaders of the future rather than dropping ill-prepared candidates in at the deep end. To support this, more resources must go into providing women with the necessary new skills, coaching, mentoring and supporting them with a personal growth agenda.

3. Coach female candidates to succeed in the boardroom. Making the transition into the boardroom successfully requires experience and a degree of training. Women will need coaching in a new set of skills to ensure they are comfortable in their new roles.

Be proactive about women

Solving the gender imbalance involves the whole industry. Executive Search firms such as RSA must work harder to identify, nurture and promote senior female executive talent. Our respondents identified three key areas where Executive Search could provide greater support:

1. Be proactive about including women in the process. Always look for female candidates, and ensure that they are brought into the process. Consider having quotas for the inclusion of women candidates in short lists for interviewing. Coach them to ensure they understand how CVs and interviews are seen by clients and ensure that job specifications are female friendly.

2. Scout harder for female talent. Men find it difficult to opt out, whereas women find it difficult to opt in. Be aware of the executive potential that is out there from the female population. Headhunt suitable women because they are less likely to put themselves forward. Consider setting up a network of top females in the industry and create events that showcase opportunities for them.

3. Promote the benefits of a mixed board. Promote the value of mixed boards and mentor the business around getting the best mix for their organisation. Encourage a diverse senior management environment by setting an example and putting forward the right mix of candidates. Strive for greater transparency in evaluating women candidates and keep stating that women need more opportunities until you don't need to say it anymore.

What this study told us is that it is vital to the overall success of Life Sciences companies that they are led by strong and well-qualified boards, made up of high calibre members with a mix of skills, perspectives and backgrounds. The positive news is that the entire industry recognises that increased female representation is a key element in remaining competitive. Women have the skills - now the industry needs to work to ensure that talented individuals have the opportunities they deserve within Life Sciences.

To achieve this change now is the time for everyone involved to review their current procedures, identify barriers and work together to dismantle them. This will ensure that the Life Sciences sector is a vibrant, competitive and successful industry built on talent, both currently and in the future. And the lessons learned by Life Sciences are equally applicable for other industries. As Lord Davies said in his report "Corporate boards perform better when they include the best people who come from a range of perspectives and backgrounds." It is now up to all of us to work together to unlock this performance.

Nick Stephens is CEO of life sciences executive services and interim management firm RSA

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.