US and Israel Pressure Germany to Hand Over €1bn Nazi Art Loot to Jewish Heirs

American and Israeli officials have turned up the pressure on German authorities, to hand over a billion euros worth of art to Jewish heirs, after valuable pieces were seized by the Nazis during World War II.

Government authorities from the US and Israel have started to lobby Germany to speed up its policy on art restitution, as well as to make the process more transparent, as potentially 1,000 heirs wait for the return of their precious works of art.

German authorities seized the treasure trove of fine art between 2011 and early 2012 but it was not until October this year that prosecutors confirmed the discovery.

As part of a tax evasion probe into Cornelius Gurlitt, the reclusive son of an art dealer in Munich, prosecutors unearthed paintings by Matisse, Picasso and Chagall.

Due to the art being seized via a tax evasion investigation, German privacy law states that authorities are prohibited from disclosing the details of probes related to taxation.

"No one can have a fair restitution-claims process without fair access to information," said Stuart Eizenstat, the US State Department's special adviser on Holocaust issues in a statement.

Other US officials have also added that Germany should aim to change its domestic regulations to uphold its international commitments on art restitution.

An Israeli foreign ministry spokesperson added that the country is also pressing Germany, in separate talks, to make its restitution proceedings more transparent as the region is concerned that German museums could be "hiding" information about the provenance of valuable works.

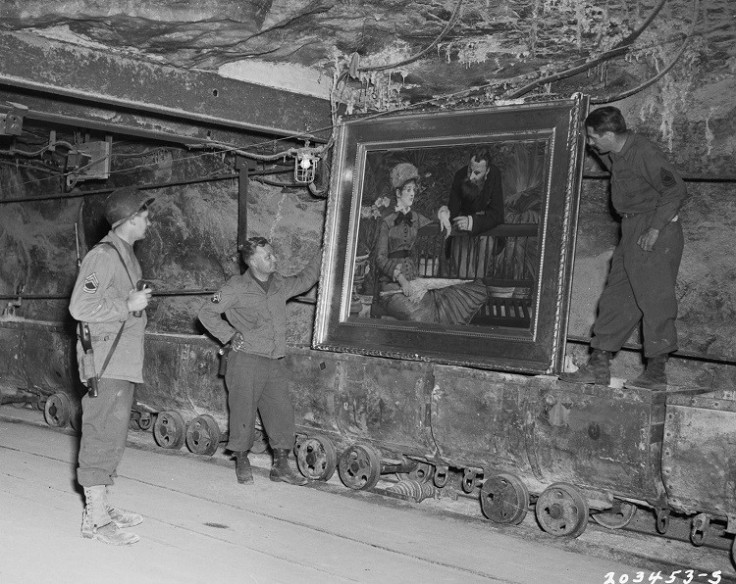

Nazi Art Treasure Trove

US lawyers have continually slammed the handling of the process of reuniting Jewish families with 1,500 pieces of art that were confiscated by the Nazis in the 1930s and 1940s.

After the valuable pieces, worth €1bn (£846m, $1.35bn), were found in an apartment in the German city of Munich, US lawyers criticised the prosecutors' decision not to publish a full inventory so that families missing art can take a closer look.

"This is the biggest find I have ever seen," said Meike Hoffmann, an art historian from Berlin's Free University in charge of assessing the provenance of the work for German prosecutors handling the probe.

One of the world's most prominent art lawyers, Larry Kaye, also voiced his dismay over the process.

"I find it shocking they won't list everything they've found," said Kaye.

"Families don't always know exactly what they're looking for until they can see an image of it."

Meanwhile, a Jewish group accused Germany of "moral complicity" in concealment of stolen paintings.

"This case shows the extent of organised art looting which occurred in museums and private collections," said Ruediger Mahlo, of the Conference on Jewish material claims against Germany.

"We demand the paintings be returned to their original owners. It cannot be, as in this case, that what amounts morally to the concealment of stolen goods continues."

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.