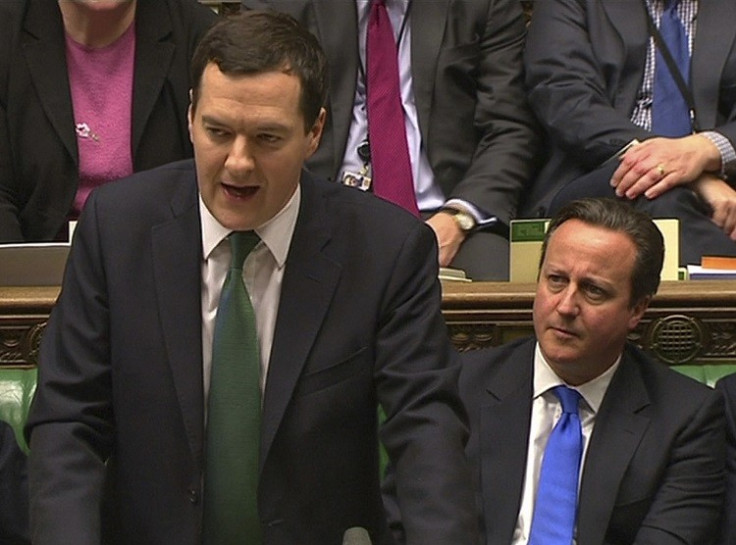

Autumn Statement 2013: Five Reasons to Fret About Osborne's Recovery

On the face of it, Chancellor George Osborne delivered a pretty upbeat 2013 Autumn Statement.

The Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR), the independent fiscal watchdog, sharply upgraded its UK growth and public finances forecasts.

In short, the UK economy will grow much faster than it thought before Osborne's March Budget, and the country's debt and deficit will fall more quickly too. In fact, by 2018 we'll be running a surplus in public finances.

But what's driving this recovery? And is it sustainable? Here are five things from the OBR report for us to worry about it.

Productivity

Rising GDP growth isn't being driven by a sharp upturn in productivity, despite the government boasting that there are more of us in work than when they first took office.

The OBR raises the alarm over the weakness of productivity. Its calculations are that productivity in the third quarter of 2013 is 12% lower than in the same period in 2008, just before the Great Recession. What's more, they expect this gap to widen rather than narrow by 2019, to 15%.

"This reflects our view that much of the loss of productivity over the recession was structural and will not return even as the economy recovers and the financial system returns to full health," says the report.

There is a suspicion that productivity before the recession was inflated artificially by the financial sector, whose output we now know relied heavily on unsustainable leveraging.

As the OBR says: "Ultimately, productivity-driven growth in real earnings is necessary to sustain the recovery."

Trade

Much of Osborne's economic strategy has centred on rebalancing the economy away from debt-driven consumption and towards goods exports instead.

This relies on narrowing the current account deficit by growing exports and stimulating the manufacturing sector.

However, the OBR report shows growth in the contribution of trade to UK GDP to be mostly flat over the coming years. In 2013, it forecasts a 0.2% fall in its contribution to GDP. In 2014 there will be 0 change and in 2015 there will be just a 0.1% increase.

Export markets

This is driven by a downward revision by the OBR of its forecasts for export growth. Why has it done this? Because our key export markets, such as the US, eurozone and emerging markets, are weakening.

"Consistent with slower global growth, world trade has been weaker than we expected in our March forecast, largely due to weaker-than-forecast trade in advanced economies and parts of Asia," said the OBR.

As a result, the OBR revised down its trade growth forecasts for both the world and emerging economies.

"Growth in UK export markets is expected to be slower than growth in world trade: the euro area and the US make up a larger share of UK exports, and import demand from these regions is forecast to grow more slowly than import demand from emerging markets," said the OBR.

"We now expect UK export markets to grow by 3.2% in 2013 and 5.2% in 2014, which is lower than our March forecast. These downward revisions reflect current weakness in euro area import growth and weaker import growth in emerging economies."

Consumption

Instead, we will be increasingly reliant on household consumption to drive the recovery from 2013 to 2018. The OBR forecasts 1.9% growth in household consumption's contribution to GDP in 2013. In 2017, this will have quickened to 2.8%.

This necessitates a reversal of the sharp decline in incomes, particularly of wages, because households cannot keep leveraging themselves with more debt, wearing down their assets or eating into their savings forever. Consumption will slow and so would the recovery.

"With real disposable income growth remaining relatively weak over the first half of the year, the pick-up in consumption has been accommodated by a fall in saving, although comparisons are distorted by the income shifted from the first quarter into the second to take advantage of the lower additional rate of income tax," said the OBR.

"Taking into account the weakness of real earnings growth, we expect the current momentum in consumer spending growth to fade, with the pace of quarterly growth slightly slower next year than the average rate over 2013."

Business investment

This might be okay if business investment picks up, so that more jobs are created and output rises. Rising output should, in theory, help push up wages as firms make more money.

However, despite the upturn in its GDP forecast, business investment remains sluggish.

In 2014, it expects business investment to rise by 5.1%. This is 1% lower than the OBR was predicting in March. Its forecast for 2015 is the same at 8.6% growth and 2016 will see just a 0.1% increase on its March forecast, at 8.7%.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.