Behind the Kurdish Oil Mystery: Cash, Power Grabs and the Battle for Statehood

Series of tankers carrying Kurdish crude oil disappeared mysteriously as cargoes were sold in secret

When the oil tanker Kamari disappeared in the Mediterranean on 1 August, it was carrying around $100m (£60.7m, €76m) worth of crude from Iraq's semi-autonomous region of Kurdistan.

Having departed from the Turkish port of Ceyhan, the tanker sailed to a spot around 200km from the Israeli and Egyptian coasts. In that seemingly innocuous location, its satellite tracking transponder suddenly shut off.

Four days later, the same ship reappeared in the same spot on global ship tracking systems. But its cargo, around 1 million barrels of Kurdish crude oil, had been unloaded.

The month that followed was marked by a series of similar vanishing acts. On 17 August, Kamari was carrying a partial load when it disappeared from ship tracking systems.

Two days had passed when it reappeared 30km from the Israeli coast, without its cargo.

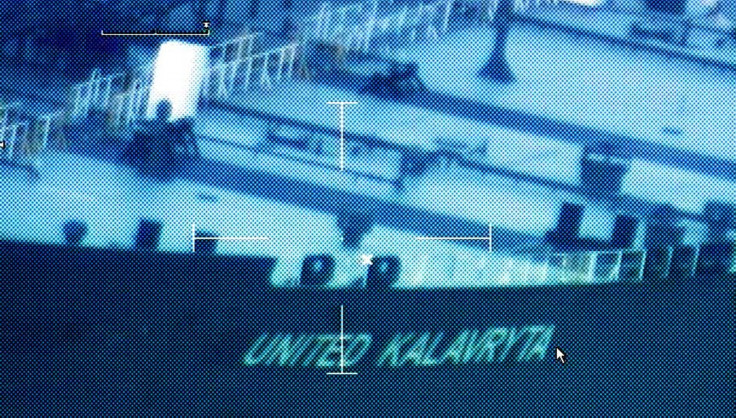

The disappearances have not been confined to the Mediterranean. On 28 August, the tanker United Kalavrvta tanker went dark off the coast of Texas in the United States.

As with the Kamari, the ship went missing for a few days, before abruptly returning at roughly the same spot from where it vanished. Yet, on this occasion the tanker had kept its cargo. On 2 September, Kalavrvta remained off the US southern coast, loaded with $100m worth of Kurdish crude.

The now-familiar pattern of behaviour has yet to be explained by the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG), which approved the export of the oil in the first place. Baghdad too has kept quiet about what it knows the specifics of the shipments, if indeed it knows anything at all.

But the disappearances reveal the clandestine way in which the KRG is pursuing its attempts to sell oil, and the lengths to which Baghdad will go to stop them.

It is a high-stakes game of cat-and-mouse being played out between Iraq and the semi-autonomous region in the north of the country.

Clash Over Oil Revenues

The Kurds of Iraq first began exporting oil on a large scale to Turkey at the start of this year, following the completion of a pipeline running from the region to its northern neighbour.

The oil was then sent to Ceyhan, where it was stored for months while Baghdad challenged the Kurds' attempts to sell it. The central government insisted that it retained all rights to sell oil produced in any part of Iraq.

The battle turned ugly, as Baghdad withheld money that was owed to the region as part of the country's oil revenue-sharing agreement. Under the Iraqi constitution, the KRG is entitled to 17% of oil export revenues, which it says amounts to $7bn for the first half of 2014.

Starved of oil revenues, the regional government could not pay wages to its public sector staff, and has said that Baghdad owed them $7bn in oil revenues for 2014 alone.

This background battle was a key factor in the Kurds' willingness to strike out alone and attempt to sell oil produced in the territory on international markets.

Baghdad Weakness

Yet, the fact that the oil remained stored in Ceyhan for months and was only first exported in May is also telling.

Iraq's national elections took place in April, amid extremely heightened tension between Sunni Iraqis and the Shia-led government of Nouri al-Maliki.

The ruling party failed to win a majority in those elections and spent the next few months struggling to cobble together a coalition.

Maliki had become an unpopular figure with his allies abroad as well as domestically, especially among the Sunnis who accused him of promoting from within his own Shia sect and marginalising minorities. Eager to cling on to power, Maliki focused on persuading enough of his rapidly shrinking coalition of allies that he was the man to lead Iraq.

Meanwhile, the Kurds sensed the weakness and disunity within the central government and convinced the Turkish government that the time was right for the oil stored at Ceyhan to be exported and sold abroad.

Bringing in the Lawyers

Once the oil exports began, the battleground moved to the high seas and eventually into foreign courtrooms.

Infuriated by the Kurds' actions, Baghdad accused the KRG of smuggling oil out of the country and threatened to file lawsuits against anyone that purchased the oil.

A case was brought in a Texas court after United Kalavrvta, loaded with Kurdish crude, was spotted heading for the port of Galveston, Texas, after apparently finding a buyer. Iraq's oil ministry filed the suit with the Southern Texas District Court, claiming that the crude oil had been stolen from the people of Iraq.

The KRG's lawyers countered that the oil was pumped in Kurdistan, which makes it Kurdish. Moreover, they argued with apparent success, US courts do not have jurisdiction to decide who owns the oil. The judge presiding over the case eventually threw it out.

"The Kurds have managed to load seven or eight tankers, and something like four or five of them have been offloaded, which implies that there are buyers out there. If you were to remove the threat of legal action, it would be much easier and I suspect that they are selling these cargoes at quite a discount," said Tom Pugh, Commodities Economist at Capital Economics.

The legal ramblings over Kurdish oil have significant ramifications for the Kurds, but the Texas case appears to show they are currently winning that argument.

Kurdish Oil Boom

While export capacity in the region is currently estimated at around 200,000 barrels of oil per day (bpd), the recent completion of a new pipeline should boost that figure to around 250,000 bpd, and experts estimate that total production could double within the coming months.

"There's massive potential. Under Saddam, the area was deliberately underdeveloped in a method of keeping the Kurds under control. This means it is one of the last areas with vast amounts of easy-access oil," Pugh told IBTimes UK.

"They are looking for around 500,000 bpd within six months or so and there's been talk of up to a million by the end of next year. That's probably ambitious given the current security climate, but it's an indication of what could happen if everything goes the right way for the Kurds," said Pugh.

The Kurds currently control the historic city of Kirkuk, which could boost their oil production capacity if they are able to hold on to the city and the major oilfield in its vicinity. Though the pipeline running from that oilfield to the Turkish port of Ceyhan is currently out of action due to sabotage, the oil and infrastructure remain a valuable prize for whoever controls them.

With militants from the Islamic State shoring up the caliphate that stretches from Syria to the fringes of Kurdistan, the Kurds' ambitions may be tempered by insecurity.

Yet, with an experienced security force and military backing form some Western countries, the Kurds may be able to assert their autonomy from Baghdad with growing confidence in the months and years ahead.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.