Blood Cancers Develop Every Day – But Human Immune System Kill Them Off

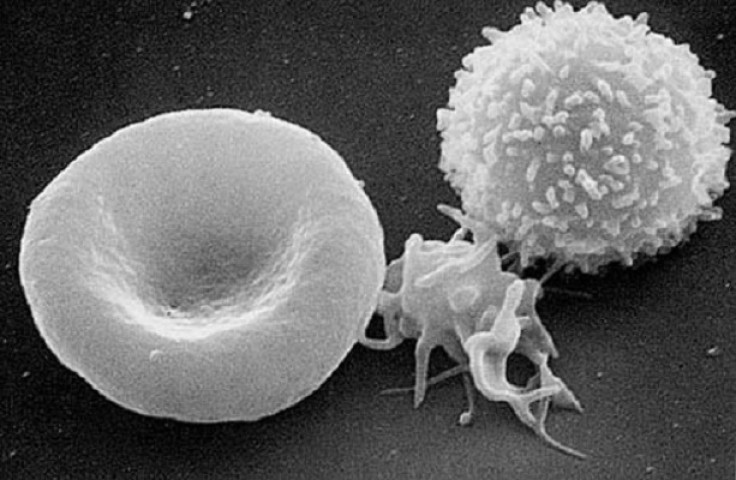

Humans develop blood cancers every day but our immune system kills them off, researchers have found.

Immune cells in the body undergo "spontaneous" changes every day that would result in cancer if our bodies were not able to detect them immediately, scientists at the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute in Melbourne have discovered.

They found that the immune system is able to eliminate potentially cancerous immune B cells in the early stages, before they develop into B-cell lymphomas – a form of non-Hodgkin's lymphomas.

Researchers said their findings account for the relative rarity of B-cell lymphoma in the population. In the UK in 2010, 12,180 people were diagnosed with non-Hodgkin lymphoma. In Australia, where the study took place, approximately 2,800 people were diagnosed with B-cell lymphoma.

In the journal Nature, the authors noted how the immune surveillance system accounts for why this form of cancer is not more common, considering how often spontaneous changes in the immune cells take place.

Axel Kallies, one of the study authors, said: "Each and every one of us has spontaneous mutations in our immune B-cells that occur as a result of their normal function. It is then somewhat of a paradox that B cell lymphoma is not more common in the population.

"Our finding that immune surveillance by T cells enables early detection and elimination of these cancerous and pre-cancerous cells provides an answer to this puzzle, and proves that immune surveillance is essential to preventing the development of this blood cancer."

People with weakened immune systems are at higher risk of developing B-cell lymphoma. The authors believe their discovery could lead to the development of early warning tests that can identify at-risk patients, meaning proactive treatment can be provided to prevent the growth of tumours.

Explaining how they made their discovery, Kallies said: "As part of the research, we disabled the T cells to suppress the immune system and, to our surprise, found that lymphoma developed in a matter of weeks, where it would normally take years.

"It seems that our immune system is better equipped than we imagined to identify and eliminate cancerous B cells, a process that is driven by the immune T-cells in our body."

Associate professor David Tarlinton, who was also involved in the study, added: "In the majority of patients, the first sign that something is wrong is finding an established tumour, which in many cases is difficult to treat. Now that we know B-cell lymphoma is suppressed by the immune system, we could use this information to develop a diagnostic test that identifies people in early stages of this disease, before tumours develop and they progress to cancer.

"There are already therapies that could remove these 'aberrant' B cells in at-risk patients, so once a test is developed it can be rapidly moved towards clinical use."

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.