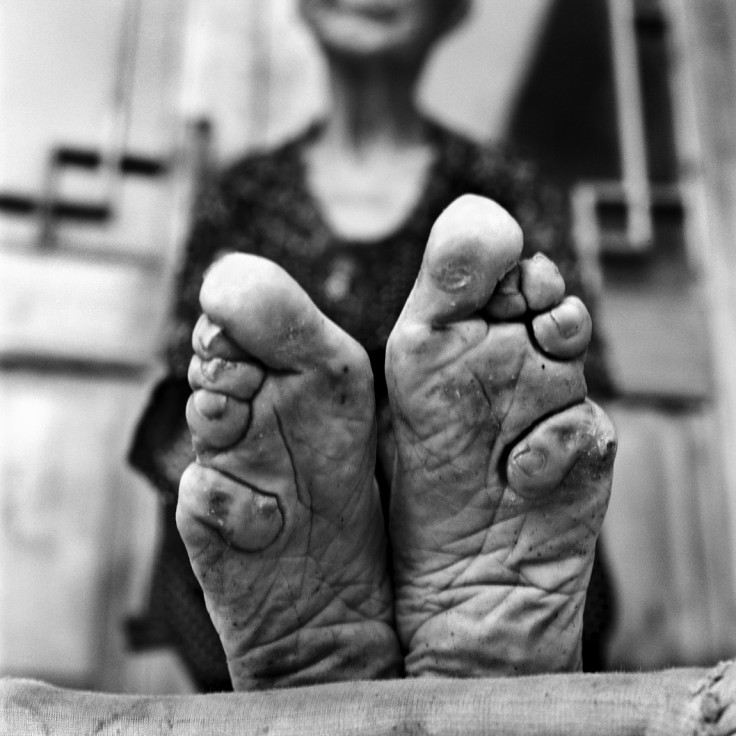

China Photo Story: The Last Survivors of Crippling Foot Binding Tradition

British photographer Jo Farrell, 48, is racing against time to capture images and interviews with the last living Chinese women to have survived the ancient abusive practice of foot binding, which is responsible for life-long disabilities.

Farrell has set up a campaign on Kickstarter to raise funds so that she can complete her project, which is to create a visual and written history of these women. The campaign has currently raised $9,544 (£5,684).

Foot binding, also known as "Lotus Feet", was a common Chinese custom that lasted for over 1,000 years, whereby painfully tight cloth bindings are applied to the feet of young girls to prevent their feet from growing any bigger.

It was believed that women with small feet were beautiful and dainty, and the practice became a status symbol that enabled women to marry well if they were able to become a prized "three inch golden lotus".

Although the practice was originally started by upper-class court dancers in the 10<sup>th or 11<sup>th century, the practice eventually spread to the lowest of classes, until it was finally banned in 1911 after Western missionaries campaigned against it.

Nonetheless, in some rural villages across China, the last remaining women who had their feet bound as women are still living, and some of them are still binding their feet, despite the ban.

"I was surprised. I thought it was a tradition that had long disappeared. The trouble is that once the toes are broken and underneath the soles, nothing except surgery will bring them back," Farrell tells IBTimes UK.

"Some of the women do still bind them because they are more comfortable. Some women I met in Yunnan province still had their feet bound. They managed to escape the government rule by wearing huge shoes stuffed with socks."

Farrell, based in Hong Kong, started her project eight years ago as she wanted to capture women's traditions that are dying out.

She had originally read about the ancient practice in books like Wild Swans and Life and Death in Shanghai, and felt that the books had glamorised the idea of foot binding, focusing on the beautifully embroidered shoes or the erotic aspect of the custom, while failing to show the women behind the tiny feet.

"[These women] are great grandmothers, or even great-great grandmothers. Most of the women I photographed are peasant farmers, harvesting cotton and sweetcorn," says Farrell.

"Some of them have multiple children. They're the last generation to have bound feet, but they also lived through the Cultural Revolution, so they needed lots of children around to help with the farm."

According to Farrell, the Cultural Revolution made things worse for women with bound feet, as they still had to work in the fields in order to receive rations.

"One lady told me that [she remembered thinking that] night was more important than day time. When everyone was sleeping, she [could] use the time to do more work than others. She won't [ever] forget the hard life of that time," she says.

"One of the women said that when she was 11, she went to her grandfather's birthday, and her aunt complained to her mother that her feet were too big, that they were like boys' feet. Her mother immediately bound her feet," Farrell recalls.

"She said it was so painful and that her feet had infections in the first year as it's difficult to cut the toe nails since they are in a different position, but then it became normal."

The process of foot binding usually occurred between the ages of four and nine, before their feet were fully developed.

Carried out during the winter months, when their feet would be numb from the cold, the child's feet would be soaked in a warm solution made from herbs and animal blood to soften the feet, and toenails would be cut back as far as possible.

The toes on each foot were then curled backward, pressed downwards and then squeezed into the sole of the foot until the toes broke.

After next breaking the arch of the foot, bandages were wrapped around the foot, pressing the toes underneath the foot.

The feet would be unbound and washed regularly, then kneaded to soften them, after which the bandages reapplied even tighter. The feet would start to heal over time, but they would still be prone to breaking again.

"It gave them an opportunity to marry into a bigger family with more land or more sheep. They would be married by a matchmaker and promised as children in marriage to another family and then marry at 15 or 16," explains Farrell.

"They didn't particularly like their feet, but they knew that that was their only way to have a better marriage."

Farrell says that when she visits villages to meet with women who have gone through foot binding, other people in the village will often say that they don't have any.

"They think that this is something of the past that shouldn't be celebrated, and I [have to] explain that I'm trying to document them as part of history," says Farrell.

"They are the forgotten women, and when I come around, they feel important. Everyone in the village comes around and wants to know what's going on. When I leave, they don't want me to go."

Farrell is hoping to use the funds she has raised to return to Shandong province in Eastern China to complete her interviews and photograph more women. Before now, she has been completely self-funded and only able to make the trip once a year.

She has so far interviewed 50 women, and over a third have died since she interviewed them. Farrell hopes to turn her photographs and written interviews (conducted with the help of a translator fluent in local dialects) into a coffee-table book by the end of this year.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.