Climate change: Micro winery machine produces wine instantly to test fermentation

Device produces wine from grape juice at a rate of 1mm per hour and cuts out 21-day fermentation process.

A machine has been created that produces wine instantaneously and non-stop. The wonder device – or micro-winery – has been developed by French and US scientists to test different fermentation processes, as climate change threatens to upset its production. But, possibly more importantly, it could also one day be made available for personal use.

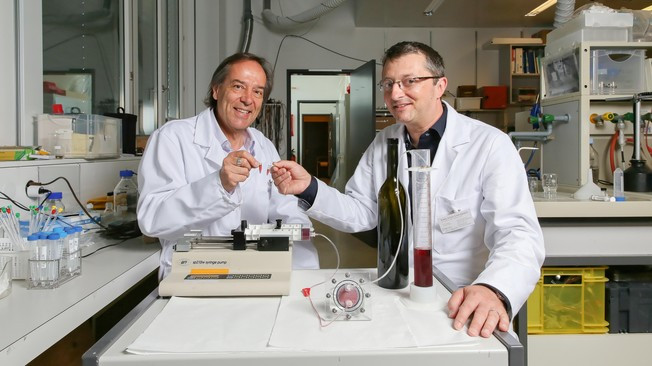

Iowa State University's Daniel Attinger invented the device along with colleagues from the École polytechnique fédérale de Lausanne (EPFL). It can produce wine from grape juice at a rate of one millimetre per hour and will allow winemakers to test out different fermentation processes far faster than they currently can.

Attinger said: "Climate change is having an impact on the quality of grape crops around the world," he said. "Due to the heat, some crops ripen too quickly, the harvest takes place sooner and the wines end up with a higher alcohol content or a different taste. We need to find ways to analyse and adapt how the wine is made."

Wine is made with yeast being added to barrels of grape juice. The yeast absorbs the sugar and releases alcohol and carbon dioxide. This takes between one and three weeks. There are hundreds of different types of yeast, each providing the wine with different flavours – so picking the best one is very time-consuming.

The micro winery works by the grape juice being pushed through a main compartment. The yeast is placed on either side and fed into the grape juice through a thin membrane – a bit like a tea bag. Because of the small size of the machine, the reaction takes place very quickly. This means more yeasts can be tested at a far faster rate. Attinger said the process takes around an hour in total.

"At a traditional winery, it takes weeks to separate the yeast from the wine, because they're mixed together. That's not a problem here," he said. "Let's say a winemaker in the Lavaux region of Switzerland finds that a certain type of yeast or a certain fermentation temperature leads to an overly bitter wine. We could quickly test alternatives."

Ramón Mira de Orduña Heidinger, a professor of wine chemistry at the Changins school of viticulture and enology, said there will be big interest among the wine-making community: "It's great. We will be able to use it to characterise different types of yeast and study their resistance to sulfites and production of acetic acid."

And on the potential for home use, he added: "Why not? But that's more of a gimmick. It uses a simplified process and the result is currently not as good as normal wine."

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.