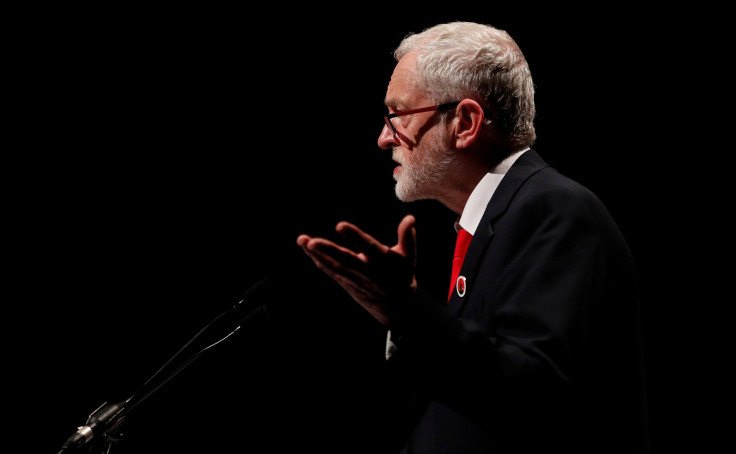

Corbyn had no Brexit policy for far too long – now Labour will pay the price

It's extraordinary that it has taken an election to finally get clarity on the biggest issue facing the UK.

If there is a third Labour leadership contest in as many years this summer – and with suggestions that Jeremy Corbyn might cling on even in the event of a Tory landslide, this is not a foregone conclusion – Keir Starmer is expected to run.

When – if – that time comes, we will look back on his speech setting out Labour's policy on Brexit as a measure of whether he is up to the job. It is extraordinary that it has taken a snap General Election to finally get clarity out of the Labour Party on the biggest issue facing the country. It's not like this is something that could have waited until 2020, when the next election was originally scheduled, because the UK would have been out of the EU for at least a year. But there's nothing like a looming deadline of millions of voters going to the polls to get your Brexit ducks in a row.

The shadow Brexit Secretary has brought clarity, of sorts. From day one, a Labour government would guarantee the three million EU citizens living in the UK the right to stay. Parliament would have a veto on the final Brexit deal negotiated with Brussels. New EU citizens would be able to come to the UK if they had a guaranteed job offer.

These measures will be welcomed by many Remainers crying out for decent representation as we prepare to leave the EU. What's more, this Europe-friendly position will suit an Emmanuel Macron presidency in France. There is fight in Labour's dog yet.

But beyond this offer to stay connected with Europe, the Labour Brexit policy is a little confused. Starmer said the free movement of people would end – because that is what leaving the EU means. And he is right. But he has also vowed a Labour government would keep the customs union and, crucially, membership of the single market, on the table with negotiations with the EU. This does not fit with the end of free movement, which is a condition of single market membership.

Labour's nuanced position, to put it in the kindest of terms, is designed to appeal to both its metropolitan Remain-voting supporters and those in northern working class seats who voted Leave last year and are planning to vote Ukip or switch straight to Conservative. With the left fracturing across Europe, Labour is facing not only a fight for its traditional voters but for its very existence. To paraphrase Tony Blair, it is not an ignoble ambition to want to appeal to both Remain and Leave voters. But there is a difference between a necessarily nuanced position to hold a coalition of supporters together and a muddle.

If Starmer can hold this policy together, then it makes him a strong candidate for the next leadership contest. But the problem is that it has come too late for many one-time Labour voters who will support another party on June 8. Under Corbyn, himself a Eurosceptic, the party's policy on Brexit has been muddled for more than a year, from the Labour leader's lukewarm support for Remain in the referendum campaign, to opposing and then supporting the government's Brexit position in Parliament. By contrast, the Liberal Democrats have set out a clear, distinctive position: pro-Remain, in favour of a second referendum, vehemently opposed to Theresa May's hard Brexit.

Those Labour MPs who have consistently opposed hard Brexit from the start can barely contain their frustration. Chuka Umunna, the former shadow business secretary who is also a potential candidate for leader, tweeted ahead of Starmer's speech: "At this #GE2017 I'm clear to constituents: I will be fighting for the UK to stay in the Single Market and the Customs union." When that leadership contest finally comes, there will be plenty of soul-searching about how Labour handled Brexit.

Jane Merrick is a freelance journalist and former political editor of The Independent on Sunday. She writes an allotment blog, www.heroutdoors.uk. Follow : @janemerrick23

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.