Esperanto: How a Jewish eye-doctor's dream of global brotherhood created a whole new language

The language is still spoken by as many as 2 million people worldwide.

When an obscure Polish Jewish eye-doctor, Ludovic Lazarus Zamenhof, invented his own language back in 1887, he made two bold claims. The first was that it was possible to learn its grammar "within one hour". The second was that his new language, which he called Esperanto, could save the world.

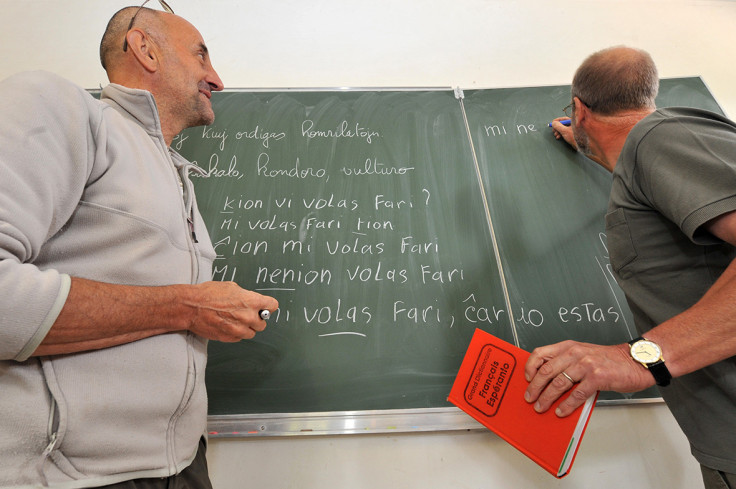

To be fair to Zamenhof, his first assertion could well stack up: Esperanto was derived from Latin languages but has none of the complexities of French, Spanish or German. It has no masculine or feminine verbs, no tenses, and it is possible to 'master' the language by learning as few as 500 words.

Given the events of the last 150 years, his second claim carries less weight, but few could fault Zamenhof's intentions. He grew up at a time of war and division in Europe, and witnessed first-hand the anti-Semitic pogroms that began in Russia in the 1880s before spreading to the rest of Europe.

His neighbours were Germans, Russians, Poles and Jews, all of whom spoke their own languages, read their own books and lived as enemies. He dreamed of a global second language that could be learned and spoken by all, protecting existing languages and bringing individuals from disparate backgrounds together.

"Anyone who has lived for a length of time in a commercial city, whose inhabitants were of different unfriendly nations, will easily understand what a boon would be conferred on mankind by the adoption of an international idiom, which [...] play the part of an official and commercial dialect," he wrote in 1887.

In a pamphlet published in Russian, Polish, French and German, he wrote that books from across the world would be translated into Esperanto. "Books being the same for everyone, education, ideals, convictions, aims, would be the same too, and all nations would be united in a common brotherhood," he said.

In that, Zamenhof got his wish. Amazon lists some 500 books in Esperanto, including the Qur'an, the Bible, the Communist Manifesto and The Hobbit. As of 2016, Wikipedia's Esperanto portal has over 200,000 articles and has 465,000 sign-ups on language learning site Duolingo. Esperanto has been less successful on the silver screen. Only four films have been made entirely in the language, including a 1966 horror movie starring William Shatner.

The most commonly cited number of global Esperanto speakers is two million, which was reached by Professor Sidney Culbert, from the University of Washington, who interviewed dozens of 'Esperantists' over several years. More recently, other linguists have estimated a more realistic number of around 100,000 fluent speakers.

But Esperanto has had some high profile supporters. It was nearly adopted by the League of Nations and later trumpeted by none other than Iran's Ayatollah Khomeini, which led to the first Esperanto translation of the Qu'ran. Khomeini is understood to have been drawn to Esperanto as an anti-imperialist alternative to English.

China has also been a long-term advocate of Esperanto, both prior to the Communist revolution and since. It was initially preferred to English as it was easier to learn, and was once taught in universities. Like in other countries, it found a strong base in Communist and socialist movements due to its egalitarian and internationalist stance.

But Esperanto not only united as unlikely allies as Chinese Communists, Iranian fundamentalists and Jewish idealists, but capitalists too. George Soros, the billionaire investor, is an Esperantist, having grown up speaking the language. His name derives from Esperanto word soros, meaning 'will soar'.

As for Zamenhof, his era proved anathema to what he dreamed it could be. He died in April 1917, amidst the ugliness of the First World War. His three children, Adam, Sofia and Lidia, would die during the Holocaust.

His language survived, and while its adherents may be on the fringes, confined to internet forums and obscure annual seminars, perhaps its origins deserve more attention. In a divided and violent world, it is worth remembering how Zamenhof chose the name for his new language: Esperanto means 'hope'.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.