Fighting crime with computers: Is predictive policing the future of law enforcement?

Predictive policing is causing crime rates to fall – but it comes with privacy concerns.

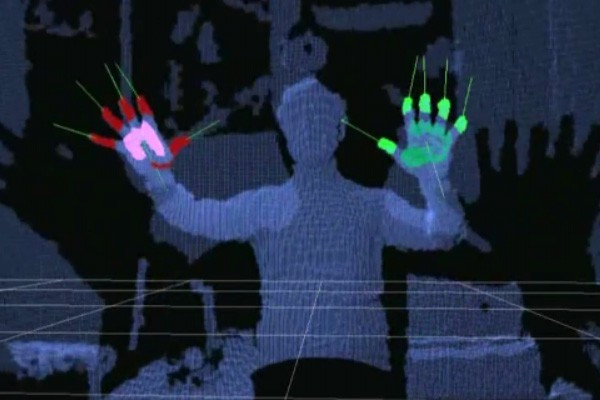

When it comes to predictive policing – using cutting-edge data algorithms and software to help fight crime – it's easy to stumble into the realm of science-fiction.

Minds will drift to Minority Report, the Tom Cruise action flick that centres on the notion of using 'pre-crime' systems to catch criminals before they act, and while police maintain this is not their intention, the increasing reliance on secretive technology to catch and judge criminals is more popular than ever before.

Pioneered by police forces in the US, systems such as PredPol and Compas have become effective tools to identify crime hotspots and highlight specific locations that need attention from law enforcement based on statistics analysis and police reports.

Despite the fact such an approach has been proven effective, it's a style of policing that comes with rising concerns over surveillance, privacy and how much power law enforcement to should turn over to computers. Is the good old-fashioned hunch a thing of the past?

The case of an incarcerated man in the US called Eric Loomis has brought attention on predictive policing back into the headlines. Loomis, 34, is currently challenging his six-year sentencing in part because it was based on the decision of Compas – a mysterious algorithm used to predict the likelihood that someone will commit another crime.

As reported by The New York Times in detail, Loomis' case highlights many of the key factors in the pre-crime debate, including how computers are given the power to decide which streets to patrol, identify people at risk of being shot and calculating the likelihood of criminal relapses.

Before his sentencing for his 2013 arrest, Loomis received a score on the Compas scale that – based on unknown criteria – suggested he was at a high risk of committing another crime.

The developer of Compas, a firm known as Northpointe, claim the algorithm's results are backed by research, but more is known about them. "The key to our product is the algorithms, and they're proprietary," said Jeffrey Harmon, Northpointe's general manager told the NYT.

"We've created them, and we don't release them because it's certainly a core piece of our business. It's not about looking at the algorithms. It's about looking at the outcomes."

Documents about the Compas system show it scores the subject on a range of topics including: criminal involvement, history of violence, substance abuse, social isolation and financial problems.

"This is just the next innovation of crime analysis — trying to get ahead of the problem, trying to predict where problems occur before they actually occur," said Eric Piza, an assistant professor at the US-based John Jay College of Criminal Justice.

Minority Report vs Reality

Yet while the programmes aim to "predict the problems", others want to create distance with the sci-fi label – which often uses such systems to signify an encroachment on personal privacy and indicate an authoritarian rule.

"This is not Minority Report," stressed Dr Jeffrey Brantingham, one professor who helped develop the PredPol predictive policing system, in a 2014 interview with The Guardian. "Minority Report is about predicting who will commit a crime before they commit it. This is about predicting where and when crime is most likely to occur, not who will commit it."

Yet the idea is spreading – Tom Cruise-inspired or not. In 2012, English police in Kent started testing the PredPol system to reduce crime in the UK – and it reportedly worked, with crime falling by 12% during the trial period.

"[The system] will identify a location where we are able to prevent crime from happening. By preventing crime, that naturally reduces our demand and therefore allows us to be more visible, more pro-active in our policing," said Detective Inspector Jonathan Sutton at the time.

Meanwhile, police in the states – which were first to adopt such tech-driven systems – have echoed similar claims. Officers from the Seattle Police Department, which incorporated PredPol into daily patrols in 2013, called it "a paradigm shift" in policing.

"Before, it was random patrol, go find something," Lt. Bryan Grenon told Al Jazeera America. "So you're successful if you write that ticket, if you make an arrest. But, in this, if you're out there and your presence alone dissuades a criminal from committing a crime, you're successful."

Yet as Mark Johnson, Kent Police's head of analysis stated this year, predictive policing has its challenges. "There's a thing called 'copper's nose' – which is the experience they have, the understanding they have, a sense when something doesn't feel right – which a computer doesn't have," he told Kent Online earlier this year.

"Without good, old-fashioned policing it wouldn't have worked. It's 21st century technology meets old-fashioned policing."

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.