First Ever Interactive Atlas of Ancient Inuit Arctic Trails Goes Live

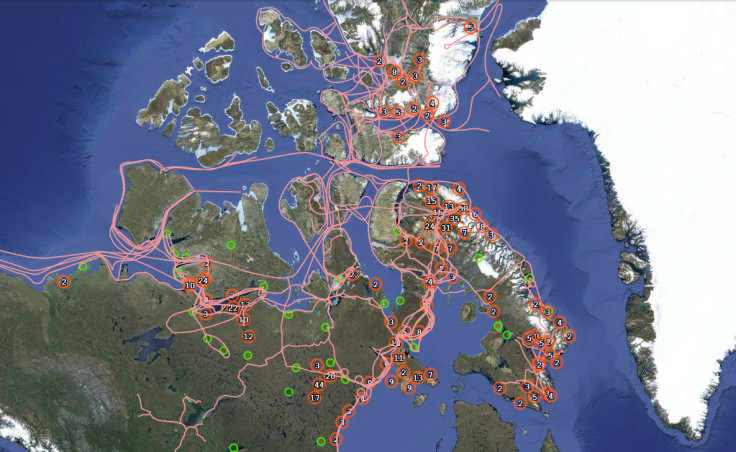

For the first time ever, the ancient Arctic routes of the indigenous Inuit peoples have been mapped onto an interactive online atlas by researchers from the University of Cambridge, Dalhousie University and Carleton University in Canada.

Over the course of centuries, the Inuit travelled across ice, seas and land in the North American continent, developing an extensive ancient network of trails that have been passed down through the generations.

The Arctic has long been depicted as "empty", i.e. an unclaimed stretch of vacant space, and today, the "pan-Inuit" world is becoming fragmented as commercial mining and oil drilling increases, while sea ice continues to diminish annually, leading to important trade routes opening up.

Pan Inuit Trails.org brings together centuries of cultural knowledge, using the published accounts of encounters with the Inuit people from the 19<sup>th and 20<sup>th centuries. It is meant to be a resource for teachers and students, but not actually for navigation.

Not an "empty" space

"To the untutored eye, these trails may seem arbitrary and indistinguishable from surrounding landscapes. But for Inuit, the subtle features and contours are etched into their narratives and story-telling traditions with extraordinary precision," said Dr Michael Bravo from Cambridge University's Scott Polar Research Institute, who co-directed the research.

"This atlas is a first step in making visible some of the most important tracks and trails spanning the North American continent from one end to the other."

The network of trails show connections stretching for hundreds of kilometres from Greenland, all the way to Alaska, with routes across the sea ice in the winter and over open water in the summer.

"Essentially the trails and the atlas reduce the topology of the Arctic, revealing it to be a smaller, richer, and more intimate world," Bravo said.

"For all that the 19th century explorers had military equipment and scientific instruments, they lacked the very precise indigenous knowledge about the routes, patterns, and timing of animal movements. That mattered in a place where the margins of survival could be extremely narrow."

Preserving their past

The atlas makes use of the Google Maps API, but the researchers have added layers of rich detail, mapping out ancient trails over the satellite imagery using global positioning systems.

Features on the atlas are marked out with anecdotes of information that the Inuits used to help them read the landscape, mostly learned through detailed accounts in the oral narratives passed down by others in their community. Most of the place names and trails are still used today.

One example is "inutturvik", which is described as being the place "where man was eaten". A note attached to the area states that an Eskimo called Ataguttaaluk turned cannibal in 1904, eating her own husband and children who had died of hunger.

"The trails are lived, remembered, and celebrated through the connections that ultimately reflect the Inuit traditions of sharing life while travelling," said Bravo.

"The geographical range of the atlas is a testimony to the legacy of the Inuit people, their remarkable collective memory built on practices of detailed observation, and motivated by an enduring sense of curiosity, as well as a set of ethical obligations to the living world they inhabit."

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.