Global warming has let moose return to Alaskan tundra for first time since 1880

Global warming in the 20<sup>th century has allowed moose to recolonise the Alaskan tundra for the first time since 1880, researchers say. Warmer and longer summers have allowed shrubs to grow taller, meaning moose now have ample food for the cold winter periods.

Research, published in PLOS One, contradicts previous studies that say moose gradually disappeared from the tundra due to late 19<sup>th century over-hunting. These studies also suggest that recent sightings of moose in central Alaska can be attributed to humans emigrating from the region.

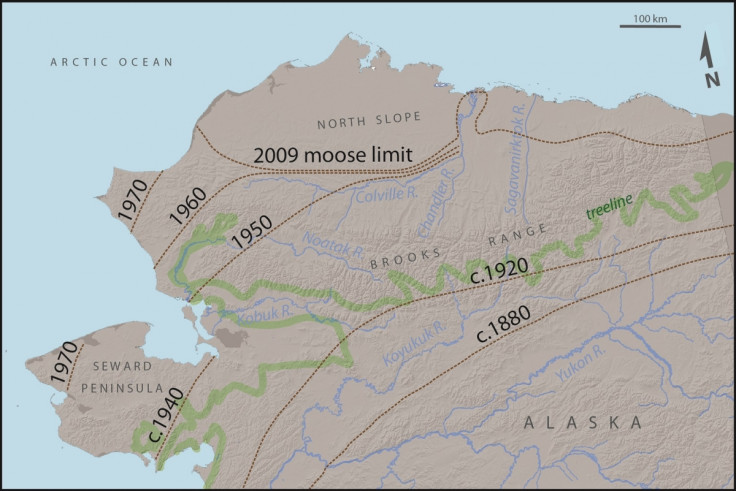

Moose inhabited the Alaskan tundra before gradually declining from 1880. By the early 20<sup>th century, they were completely absent. Since 2009, moose have been reported in the Alaskan tundra.

Researchers from the University of Alaska wanted to investigate whether their food supply had any relation to their disappearance, and subsequent reappearance. Moose rely on shrubs for food throughout the winter. These shrubs have to be tall enough to peak through the layer of snow lying on top of them, otherwise the moose cannot eat them.

The scientists compared estimated shrub heights from 1860 to 2009; a period that saw a global temperature rise of 0.8°C.

They found the shrubs had grown from 1.1m to 2m since 1860, meaning more forage was sticking up from the snow, ready to be eaten. The researchers suggest this means the shrubs were too short to be eaten before the 20<sup>th century.

As temperatures have warmed over the past 150 years, the shrubs have benefitted from a longer growing season in the summer months. The scientists say that this has allowed moose to move north into the tundra regions, as they now have plenty of food available.

"We showed that the large-scale northward shift of moose was likely in response to their increasing shrub habitat in the tundra," said Ken Tape, a researcher working on the study.

Tape added: "Although scientists have been anticipating changes to wildlife in response to the observed changes climate and vegetation of the Arctic, this is one of the first studies to demonstrate it."

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.