Gut bacteria carrying a person's unique signature can identify individuals

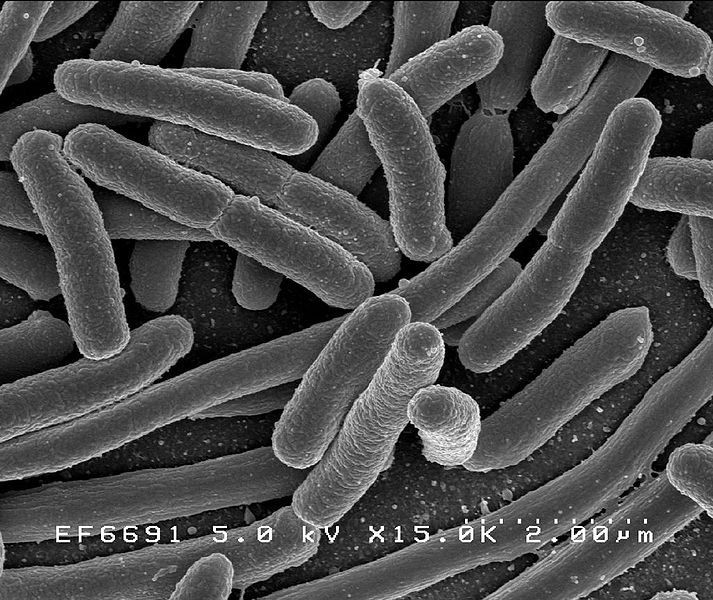

Microbes in the gut carry the unique signature of the human body they colonise and can be used to identify the individual, note two studies raising privacy concerns.

A study of the body's microbiome, the map of all resident microbes, can reveal details about the person's health, diet or ethnicity, says a study published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Another study in Genome Research says that such a publicly available data of microbiome DNA maintained by the US National Institutes of Health (NIH) already contains potentially identifiable human DNA.

While naming individuals on the basis of their microbiomes is currently difficult, the microbiome of an individual is unique, warn the researchers, concerned about lack of privacy surrounding genome research.

"Right now, it's a little bit of a Wild West as far as microbiome data management goes," says Curtis Huttenhower, a computational biologist at the Harvard T H Chan School of Public Health in Boston, Massachusetts, who led the latest study. "As the field develops, we need to make sure there's a realisation that our microbiomes are highly unique."

Data from human-microbiome studies usually ends up in public repositories. Doubts remain if microbiomes remain permanent in humans or are subject to change.

Huttenhower's team searched samples taken from body sites, including the gut, mouth, skin and vagina, for combinations of microbial genetic markers unique to a person and stable over time.

Stool samples were the best bet with microbiome signatures able to link a person's first sample to their second sample 86% of the time.

By contrast, skin samples could be accurately matched only about one in four times, writes Nature.

Where a single study may not link to an individual, multiple microbiome studies could zoom in on the person.

Microbiomes could also pose a privacy risk when they get jumbled up with human DNA. Such contamination is still common despite attempts to weed out human DNA out of HMP databases.

In 2013, scientists demonstrated they could name five people who had taken part anonymously in the international 1,000 Genomes project, by cross-referencing their DNA with a genealogy database that also contained ages, locations and surnames.

Researchers should take reasonable steps to protect privacy, says Yaniv Erlich, a computational geneticist at the New York Genome Center who led the team that identified participants in the 1,000 Genomes study.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.