Heartbreaking drawings of home by Syrian children living in refugee camps in Turkey

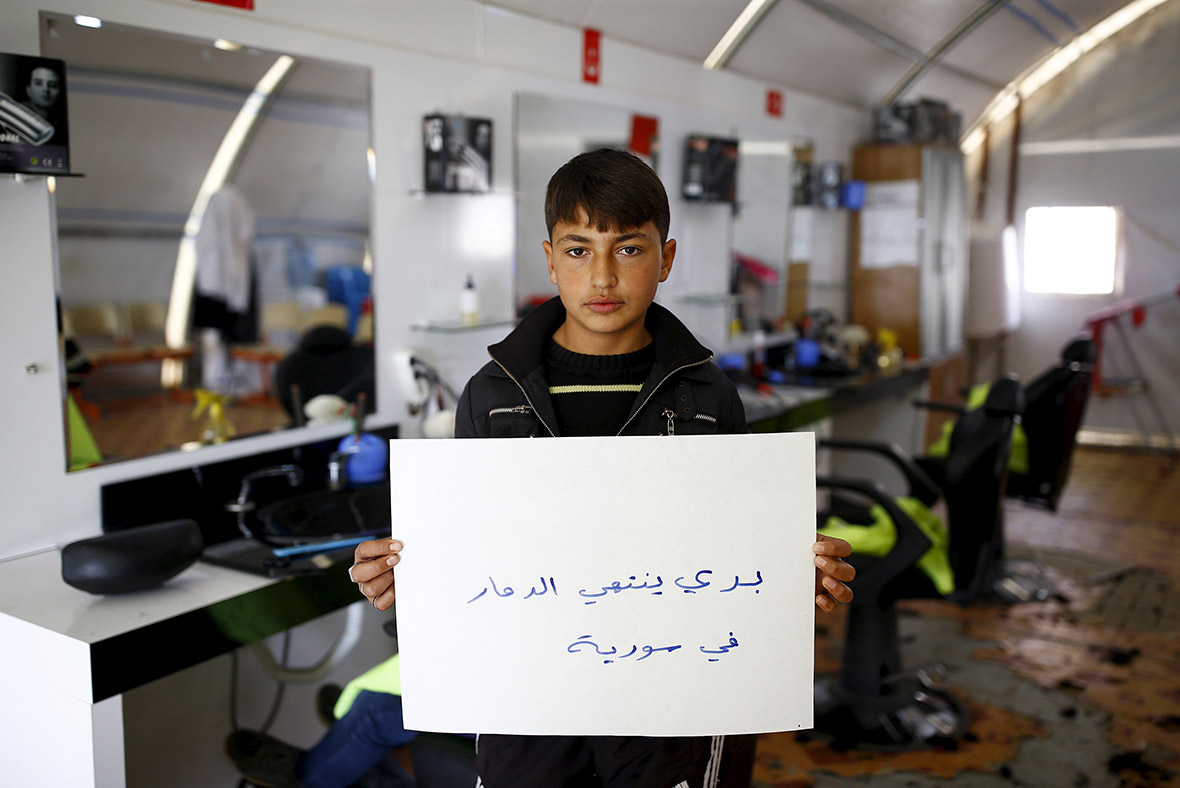

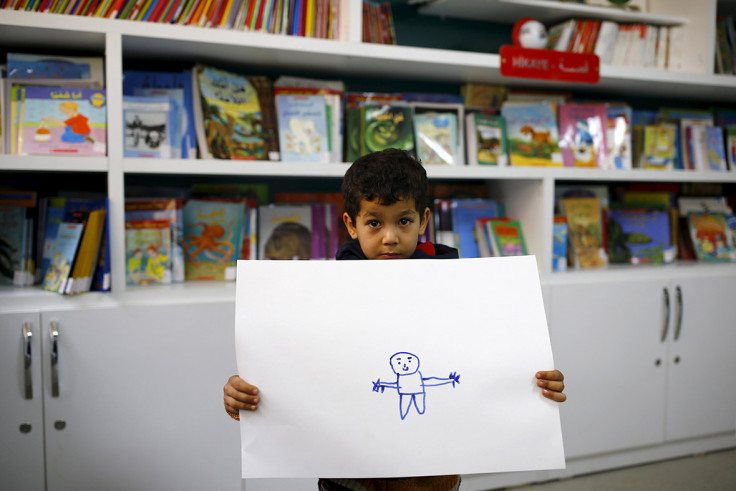

The conflict in Syria is approaching its fifth year, with no end in sight. Hundreds of thousands of Syrians have lost their lives, and millions have been forced into exile. Around 2.3 million Syrian refugees live in Turkey, more than half of them children. Many of them dream not of Europe, but of returning to their homes in Syria. Reuters photographer Umit Bektas visited several refugee camps in Turkey and asked children to draw or write down their wishes.

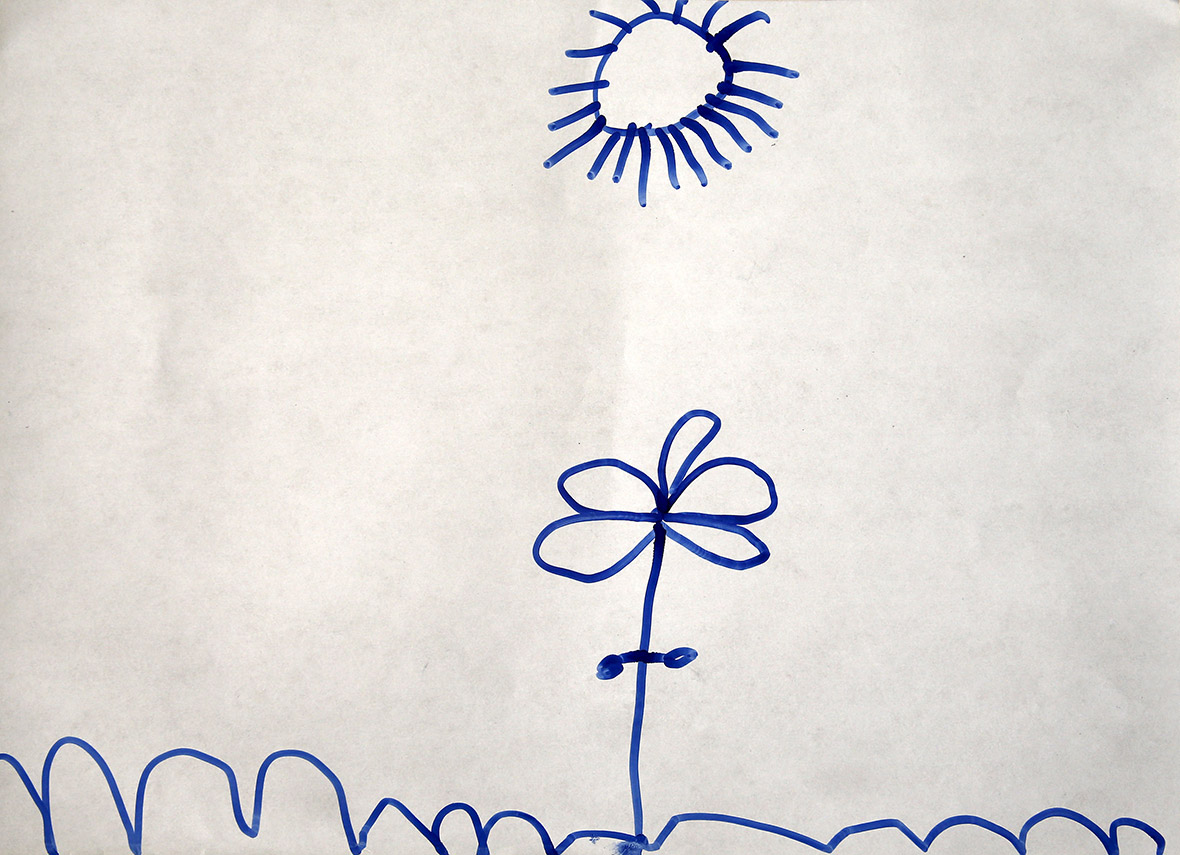

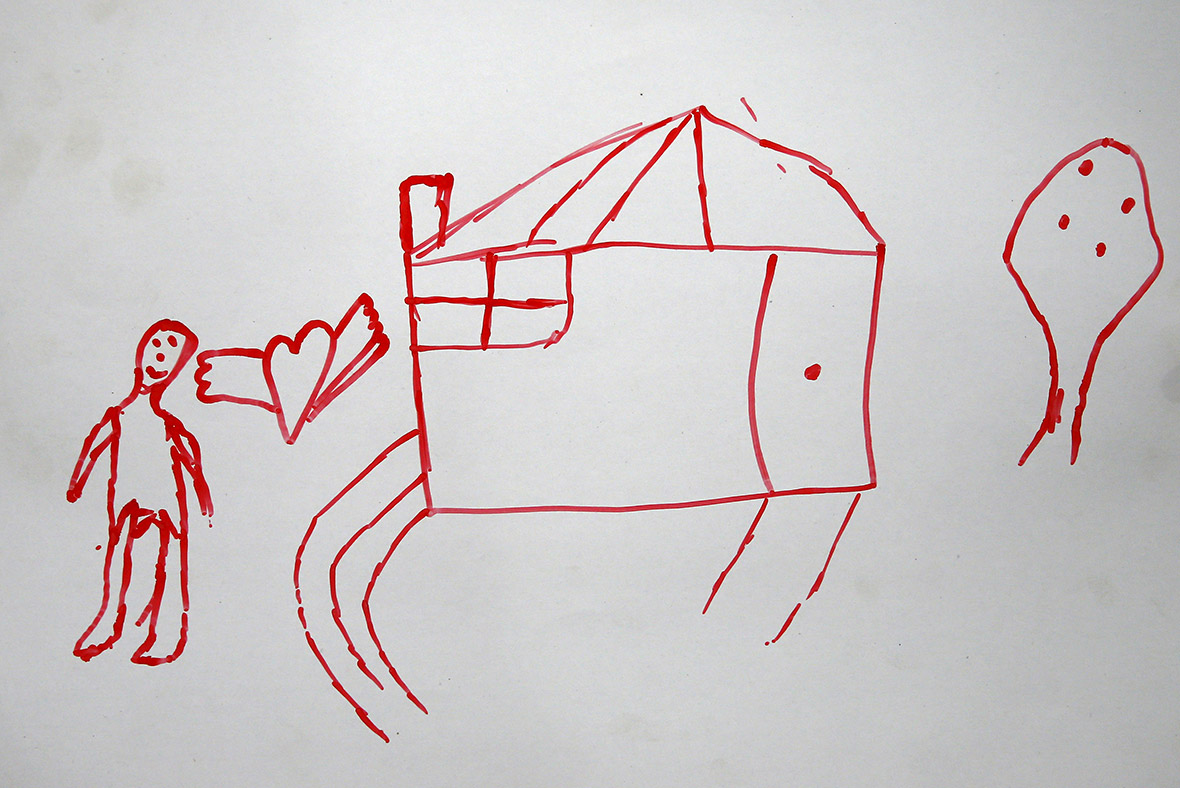

The bloodshed has had a profound effect on many of the children in the camps. Nine-year old Ilaf Hassun drew a picture of her home: a simple house, with trees and clouds with smiling faces. Then in red pen, she added the figure of a woman clutching her dead child walking towards a cemetery.

Hassun and her family are living with nearly 3,000 other people – 1,000 of them under 12 years old – in Yayladagi Refugee Camp, a former tobacco factory converted by the government just across the border from Syria in eastern Turkey.

Tesnim Faydo, eight, a Syrian refugee girl who lives in Yayladagi refugee camp, also drew a similar scene showing the effects of the war: a mother crying for her wounded and bleeding daughter next to a grave.

Meryem Dolgun, a youth worker, said: "They draw tanks, war planes, dead people, wounded children, crying mothers. Drawings are the evidence of their trauma, the reflection of their inner worlds." The most severely traumatised are sent to specialist hospitals, but the rest are given support within the camps.

The need to provide schooling and a future for Syrian children in Turkey – and prevent what Dolgun called a "lost generation" – is a high priority. However, with just 330,000 places available in camps, and many refugees preferring to take their chances begging or working illegally in Turkey's major cities, only a fraction of children are receiving help.

The Turkish government, aided by the United Nations and non-governmental organisations, has set up 27 "Kid-Friendly Fields" across the country, used by an estimated 100,000 children between the ages of four and 18 who receive support and education, and a chance to be children. The centres are the latest effort by authorities to ramp up their humanitarian response and provide long-term care for refugee communities unlikely to be able to return for years.

Providing mental security as well as physical shelter is one of the challenges facing Turkish authorities. "We have to find a way to let these children forget the war and what they experienced," said Ahmet Lutfi Akar, president of the Turkish Red Crescent. "These (children) grow up in camps. We have to teach this generation that problems can be solved without fighting, and we have to erase the scars of war."

Six-year-old Gays Cardak is already planning to use what he learns at school in Yayladagi to help his country, shattered by nearly five years of war. "I'm going to be a doctor and an engineer. We the engineers will rebuild Syria, and I'll take the (soldiers) to hospital," he said.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.