Iron Age Precursor to Channel Tunnel and First Gallic Boomerang Discovered in France

It seems that in prehistoric times before the Romans, the Anglo-Saxons and Normans might have once been friends, as French state archaeologists have discovered the remains of an ancient Iron Age port that was probably a precursor to the Channel Tunnel.

Archaeologists from Centre national de la recherche scientifique (CNRS), a French government research organisation have discovered traces of an ancient port in the historical seaside town of Urville-Nacqueville, Manche, that shows signs of trade with England, as well as ancient dwellings that bear a striking resemblance to those in Dorset.

"We did not really know what the Gauls maintained relationships with their neighbours on the continent of future Britain," University of Burgundy researcher Anthony Lefort, who led the CNRS excavation, told French daily newspaper Le Monde.

Urville-Nacqueville is a modern commune in Lower Normandy made out of two historical villages that were almost completely destroyed in WWI and WWII.

Through excavating in coastal marshes often waterlogged with seawater since 2009, the archaeologists have discovered remains of a wide array of goods and currency, including bracelets made from black shale and eight Celtic gold coins.

The shale likely came from Dorset, just 100 miles away, where in the early 20<sup>th century, archaeologists found a Stone Age quarry complete with weapons and implements at Hengistbury Head, a headland that juts out into the English Channel.

In 2012, CNRS archaeologists found a necropolis near La Tène on the Urville coastline consisting of 64 graves with no less than 75 bodies inside. Some of the adults had been buried in a foetal position, a tradition from Stone Age Dorset.

In prehistoric Gaul, the dead were usually burned on a funeral pyre, so it is possible that English immigrants were very welcome in Manche.

Foundations of ancient homes excavated on the coastline show the dwellings were round, like those found in Dorset, which is not typical to the Normandy region, where homes of the period were rectangular in shape and built to be heavily fortified hill fortresses.

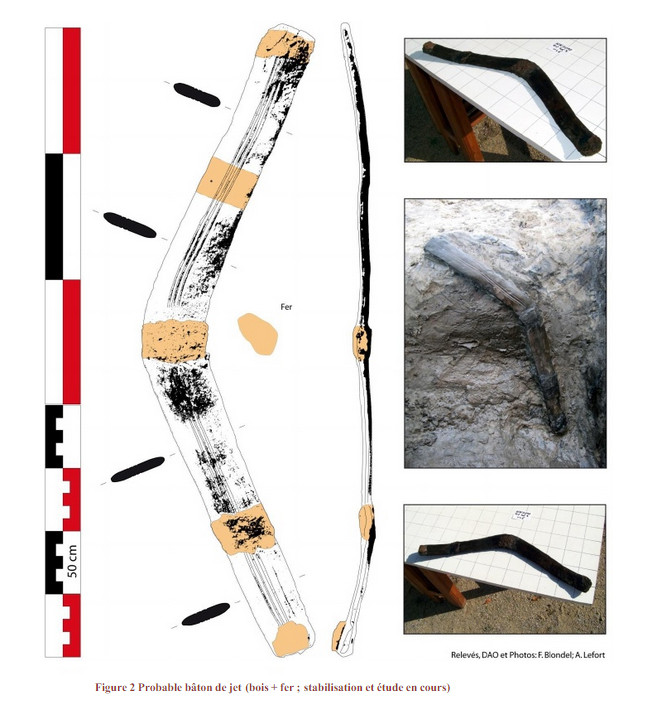

First Gallic Boomerang

The archaeologists have also discovered the first Gallic boomerang in an old ditch, a flat piece of light wood that is slightly curved, believed to be from either a pear or apple tree.

The wood was cut at the curve of a branch, weighing 150g and measures half a metre wide and slightly less than 10mm in thickness. Carbon dating places the stick at 120 to 80 BC, which is about 30 years before Julius Caesar began his conquest of Gaul.

Boomerangs have been found all over the world, including in Europe from the Stone Age, and in ancient Egypt 3,300 years ago, Pharaoh Tutankhamun was buried with a whole collection of different boomerangs, but Australia's boomerangs are the oldest, dating back to 10,000 years ago.

The "throwing stick" discovered by the archaeologists has meticulously polished blades and defined edges, similar to how an aircraft's wings are designed, making it possible for it to reach great heights.

The archaeologists say that the throwing stick was not designed to return to the thrower. Gallic hunters would have used the stick to hunt birds by throwing the stick at a flock of birds already in the air or taking flight.

While excavating the site at Urville-Nacqueville, the archaeologists have found numerous bones belonging to geese, seagulls, gannet and scaups, all seabirds native to the marshes in the area.

A research paper about the Gallic boomerang will be published in the next issue of Gallia, a journal published by the CNRS that focuses on French and Celtic Roman archaeology.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.