Iron Age warriors were better at breeding horses – we've ruined them with inbreeding

Analysis of ancient bones paints a picture of healthy, sturdy horses.

We could learn a thing or two about horses from the warrior nomads of the Eurasian steppe. The people who lived in what is now Kazakhstan in the 1st Millennium BCE were among the first to breed horses for riding – and they managed to get results without resorting to inbreeding, a new study finds.

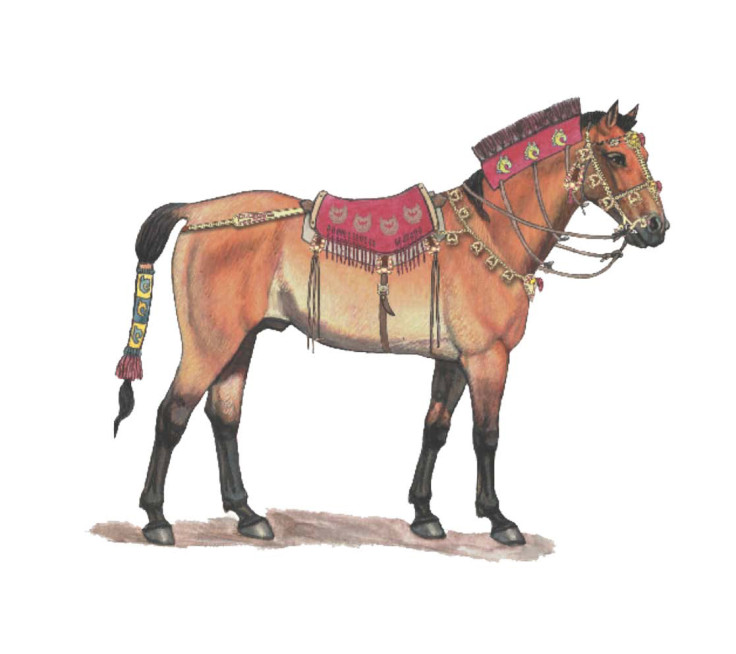

In Iron Age Kazakhstan, hundreds of horses were ritually buried at royal funerals. The sacrifice of so many horses at a funeral was a sign of the animals' importance to the Scythian people. For the first horseriders of the Iron Age steppe, this new way of travelling and fighting transformed their lives and cultures.

Ancient bones

Genetic analysis of the bones of 13 horses, buried between 2,300 and 2,700 years ago at a site called Berel in Kazakhstan, has revealed the nature of the horses that the Scythians bred and how they bred them. The findings have been published in the journal Science.

"We have strong evidence for selection at 121 genes. Amongst those genes there is a high number related to the way the horse develops," study author Ludovic Orlando, of the Natural History Museum of Denmark and the University of Copenhagen, told IBTimes UK.

"They were not interested in the Arabian type of horses, but something with robust and probably stronger legs."

The Scythians also bred horses for a range of athletic abilities, from sprinting characteristic of today's racehorses, to endurance for gruelling treks across the steppe.

Origin of colourful coats

The horse bones also revealed a strange quirk brought about by the Scythians' horse breeding. Selecting for traits for tameness, such as a weakened fight-or-flight response, had unexpected effects on several well-known characteristics.

This selection acted on a group of cells known as the neural crest. As well as breeding calmer horses, altering the neural crest also affected their coat colour and the shape of the face. The Scythians ended up breeding horses with bay, black, chestnut, white and spotted coats as an accidental by-product.

This is a feature in common with many kinds of domesticated animal, from pigs to dogs.

"We could use the horses to test something that could apply to the animal domestication process as a whole," Orlando said. "If you select for one thing, you get a lot of traits coming along with those. You have some that are extremely typical of domestic animals.

"So that means that what you see in the animals today is not necessarily a reflection of what people wanted to achieve. They just wanted to achieve tameness," he said.

The benefit of many stallions

Unlike modern horse breeders, the Scythians did not go in for inbreeding when cultivating their herd.

"The stallions were a lot more diverse than our stallions today," Orlando said. "They really valued diversity back then. We also found that the Scythian horses were not inbred. Inbreeding is one of the characteristics of how people breed horses today. There has been a huge change in the way we interact with horses in past millennia."

Instead they maintained the horses' natural herd structure in their breeding efforts. In short, the more stallions the better, leading to more diversity and less inbreeding. This avoids a build-up of harmful genetic mutations that give horses the health problems that come with intensive selection.

The findings overturn a long-standing theory of domestication. Biologists argued for many years that taming a small number of animals and breeding from them would inevitably lead to a large burden of harmful mutations, known as 'genetic load'.

This is because when just a few animals are captured from a much larger wild population, the gene pool available is tiny. This means that any harmful mutations present can't be easily bred away, and a large portion of the population will carry them. Today, there is very little diversity in the male sex chromosome in horses, as most horses alive today descend from very few stallions.

Moderns or Romans to blame?

If the loss of diversity didn't happen at the start of domestication or when people started breeding horses especially for riding, this bottleneck must have happened later. Exactly when is still uncertain, Orlando said.

"We don't know if this is a very, very late result – for example in modern horseracing – or if it was already at play during ancient times," Orlando said.

"Now we want to find where and when this happened. Was it the Romans? Was it the rise of chivalry or was it just the creation of the modern breeds through intensive breeding?"

The Iron Age horses of this study are thought to have been among the first used for horseback riding in the 1st Millennium BCE. However, some estimates put the first sophisticated horseriding in Mongolia at 1200 BCE. The exact date when horses were first ridden is hotly contested.

The next stage of Orlando's research is to find an answer to when this happened throughout Eurasia in an ambitious project to map the genetics of horses from the last 5,500 years.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.