From KKK Grand Dragon to Anti-Racism Crusader: The Remarkable Reinvention of Scott Shepherd

Time has not been kind to the Ku Klux Klan. A century ago, it struck dread into the hearts of Americans; now it is a sad anachronism, inspiring only pity and disgust.

With its weird honorific titles, which sound like it was coined by a bunch of geeks playing Warhammer, and its costumes, which would look embarrassing at a child's Halloween party, the Klan is seen as a caricature, a risible parody of an evil organisation.

Given the contempt in which we hold the Klan, it's almost hard to imagine its members are real people, capable of real human emotions such as empathy or remorse. Yet the case of Scott Shepherd challenges some of our tropish stereotypes and suggests even the most fanatical Klansman can change their ways and learn from their mistakes, just like the rest of us.

Shepherd, a former Grand Dragon of the Klan in Tennessee, is now one of America's most ferocious anti-racism campaigners, having turned his back on the KKK and made it his life's mission to defeat the creed he once espoused. The people he once called friends have sent him death threats, yet still he carries on, desperate to atone for the sins of his past.

The story is even more remarkable when one considers Shepherd's drift into the KKK was itself a 180-degree reversion of what had gone before. Neither his father, a Mississippi boatman, nor his mother, a schoolteacher, was racist; in fact, they employed a black nanny to raise Shepherd and his four siblings. Shepherd still refers to the nanny as his godmother and says: "They raised us, whipped us and everything. My godmother was actually a mother to us."

Shepherd was born in 1959 and raised through what he describes as a "period of integration" across the south, which saw black and white people begin to mix in schools in an attempt to foster harmony. This had profound consequences on his views of black people.

"My mother was sent to an all-black school, where there was a lot of violence, and she resigned to get away from that," he recalls. "Meanwhile, I was sent to a black minority school - we were told: 'Load up your books, all your possessions.' They were simply loaded on to a cotton trailer and taken away.

"I was one of about five students who were white in a school of 300 blacks. It was not a culture shock for me, but it was a culture shock for the black students. We had a lot of violent conflict, there were fistfights in the playground and the classroom all the time."

Shepherd's own family background didn't help. "I came from a family that was very dysfunctional, my dad was an alcoholic and there was a lot of family turmoil. I was a very shy, unhappy child with low self-esteem. I was looking to fill a void and I had first learned about the KKK in history books in school," he says.

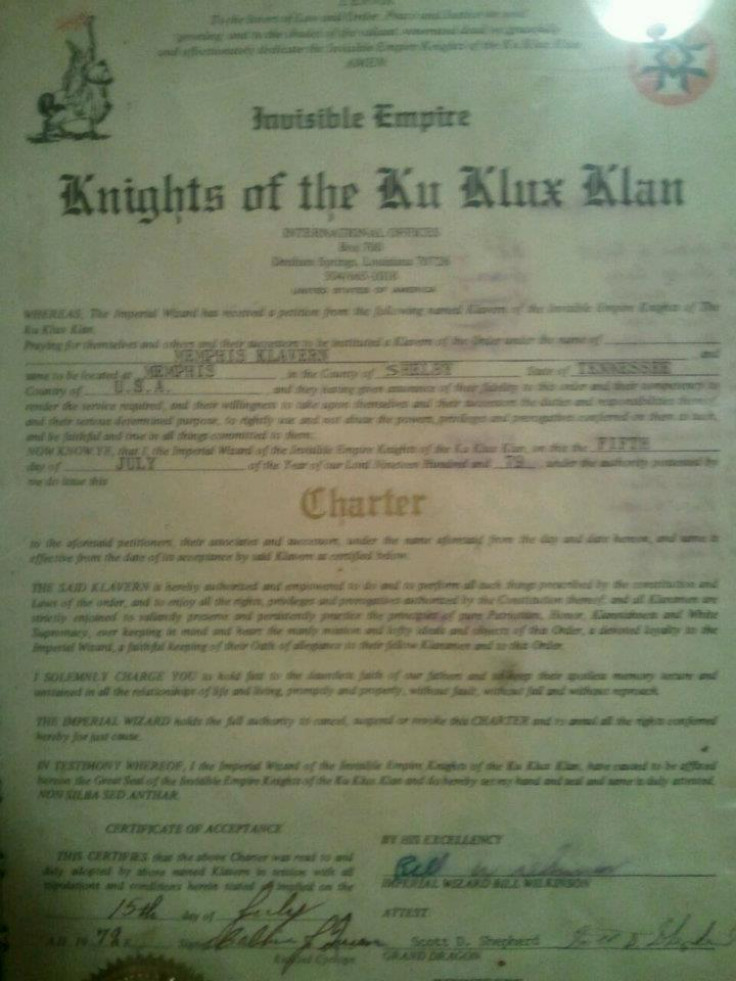

"I read a lot about it, it struck an interest in me. I made contact with a Klansman when I was 16 or 17 years old, they were having a rally in a nearby town. I went, and not long after I was contacted by one gentleman and recruited to into the KKK. They gave me a home, a sense of well-being, a family. It was definitely a tactic to recruit troubled kids like me."

Growing association

Although Shepherd married at 19 and went to college, where he studied to become a funeral director, he refused to renounce his ties with the KKK. In fact, his association grew stronger as the organisation tightened its emotional grip.

"I went through a period of indoctrination, where they gave us classes in the Klan philosophy. They taught us: 'Here we are, we are the white race, the most supreme race on the earth, minorities are second.' They threw religion into it, some Bible verses they had distorted," he says.

They gave me a home, a sense of well-being, a family. It was definitely a tactic to recruit troubled kids like me.

"They used me as a recruitment person. I attended rallies, went and talked to people. [As a funeral director] I wore a suit and tie every day and they used that to show they were good people. We targeted just about everyone, going as far as placing ads in papers. We had recruitment drives, letter drops, rallies, private meetings at people's homes.

"I did get involved in the violence as well. There were times when I was involved in intimidation, cross-burnings in people's yards and businesses, assaults, beatings. I'm just as guilty as anybody. But I was never involved in killing people - the Klan operated with a system where they used certain people for certain things, and I wasn't part of the elimination units.

"We beat white people too. We attended one movie in the 1980s, the name was Betrayed, based on white supremacist organisations. We were making comments during the movie, rooting them on. A group of people behind us started making comments, it escalated into a violent situation, some of them went to the hospital."

At the start of the 1990s, Shepherd had been involved in the Klan for 15 years and had risen to become Grand Dragon. He was also a member of the White Citizens' Council, and the Southern Nationalist Party - "if there was an organisation out there with any kind of white supremacist views, there was a good chance I had a connection".

He had even gone on national TV in New York to promote the Klan and was about to stand as governor of Tennessee in an attempt to spread his racist views further.

Saved by a black lawyer

Yet Shepherd's meteoric personal rise had brought problems. He had married and divorced twice; he says both marriages failed because of all the negative publicity he was getting, while his children had become estranged. Furthermore, as a "face" of the KKK, Shepherd had attracted the attention of the FBI, who had visited him at work and questioned him about a string of mail bomb attacks, which had killed a federal judge and civil rights lawyer.

The turning point eventually came when Shepherd visited a restaurant in Nashville in 1990. "I had a few drinks, then I left. I got down the road, looked in my rear view mirror and saw lots of blue lights. I failed a sobriety test and they found a pistol," he says.

"That threw me into the court system, I had to appear before the court and I got a black lawyer. I thought, given what I stood for that time, he was going to get me fried. But didn't, he defended me, and I remain friends with that attorney today."

Instead of going to jail, Shepherd was sent to an alcohol rehabilitation centre, which once more brought him face-to-face with the people he had spent his life oppressing.

"The centre's director told me they had black patients there and told me I'd have to share cabins. I said I didn't have a problem with it, I just wanted to do my time and then go home. But I was exposed to all kinds of people and all religions, I had to do counselling sessions and group meetings with all the other patients, we got to share stories. They [the black patients] were very stand-offish when I first entered, they'd read it in the newspaper, but I wasn't treated bad," he says.

"The first morning I sat in the group area, a gentleman called Mike was ironing a white shirt, the next thing he was ironing white pants. Then, with his white outfit, and with an accent trying to be southern, he walked up to me and said: 'You know, I think I want to join the KKK.' At that moment the ice was broken; everyone broke out laughing,

"That gave me some relief on the inside, I was able to talk and associate with a lot of these patients, we sat down and talked to each other, sharing intimate stories. I learnt Scott Shepherd didn't had a problem with other religions or sexual preferences, Scott Shepherd had a problem with Scott Shepherd."

Although he claims he "left the centre a different person", Shepherd didn't cut his ties with the KKK straight away; he was in too deep for that. Eventually, he found out his daughter had got married without inviting him, because she had black friends and didn't want her father anywhere near them. "It hurt me," Shepherd recalls. "I got to thinking and said: 'You know, this isn't worth it any more, I no longer feel the way I used to.' I walked away in 1992."

After severing his association with the Klan, Shepherd became something of a recluse, embarrassed by his past yet afraid of creating a new identity. He didn't begin the final stage of his journey until 2008, when he was seriously ill with stomach ulcers.

"My sister had been very ill with cancer in 2005, I'd had to go and take care of her. I'd told her I regretted what I did and she'd said I could use that experience to speak out and help people," he says.

"During that time in hospital I had a lot of time to think and I remembered what my sister had said. I went through a period of depression and eventually said I didn't want people to remember me for what I was all those years ago. I realised I could help young people to keep them from getting involved in white supremacist gangs, and avoid the recruitment tactics of these groups.

"I started by writing a blog, basically trying to apologise. My relationship with my family got better - everyone took my apologies, even black people. I went to the black family who raised me, knocked on the door, they opened their arms and said 'don't worry about it'. It was really touching. My godmother will be 100 years old on 2 October and my brothers, sisters and I are going to her party at the BB King museum in Indianola. Their forgiveness was like a truck lifted off my shoulders."

Death threats from the Klan

Shepherd now runs two blogs against racism, and visits schools and colleges to tell pupils about the perils of the Klan. He has appeared in tandem with Daryl Davis, a black musician who runs a radio talk show, and the pair are planning a national association for young people, giving them the chance to be part of something and avoid the sort of void that swallowed him up as a teenager.

He has even gone toe-to-toe with the Klan in an attempt to get them off his turf.

"Almost two years ago they had a Klan rally in Tennessee, they were expecting violence, so I came out and was part of a planning committee to ensure there was no violence between KKK and rival groups. I tried to contact the Klan and stop them coming to town, although it didn't work out well," Shepherd says.

"I got a lot of threats, death threats, and I still get them today, people telling me I'm going to be assaulted, but I've become pretty much accustomed to it now. It [an actual attack] has never happened yet, all it is just verbal threats and phone calls. They won't stop me."

While the Klan may have long since descended into risible obsolescence, racism has certainly not been destroyed, in America or elsewhere. If Shepherd can succeed in steering young people away from the path he once trod, he will have fulfilled his mission and earned the forgiveness he is now risking his life to achieve.

Visit Scott Shepherd's blogs by clicking here or here. You can also get in touch with him on Twitter.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.