Martian Life Probably Existed Underground: Study

The most likely locations for microbes on Mars to grow were under the surface in wet environments warmed by hydrothermal activity, according to a new study published in the journal Nature.

This adds a new angle to the longstanding debate about how hospitable Mars would have been to simple forms of life. The authors of the study assert that if life ever existed on Mars, then the proof for it would exist beneath the surface.

"If surface habitats were short-term, that doesn't mean we should be glum about prospects for life on Mars," said Bethany Ehlmann, lead author of the study. "But it says something about what type of environment we might want to look in."

This authors examined different types of clays on the Martian surface. "The most stable Mars habitats over long durations appear to have been in the subsurface," said Ehlmann.

"On Earth, underground geothermal environments have active ecosystems," she said, leaving open the possibility that such conditions may have existed -- or even may exist -- on Mars.

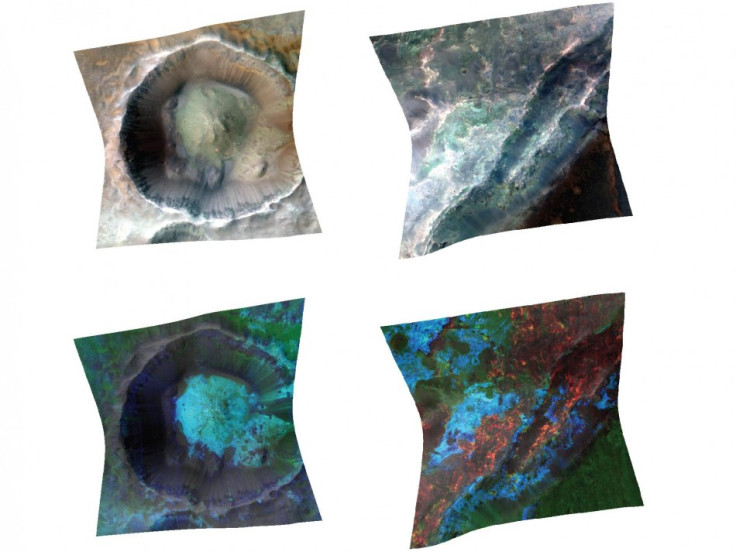

The study was conducted by employing data collected by NASA and European orbiters as they wandered around the planet for years, mapping the minerals on the Mars surface. About 350 sites were examined.

While studying the clay samples from these sites, researchers came to the conclusion that underground activities had much more to offer than surface activities. This researchers detected a mineral at these sites called prehnite, which forms at temperatures above about 200 degrees Celsius.

A co-author of the study, John Mustard said: "The types of clay minerals that formed in the shallow subsurface are all over Mars. The types that formed on the surface are found at very limited locations and are quite rare."

Examining the clays on Mars will open a window on whether the environment was hospitable for life there, according to the authors.

"Our interpretation is a shift from thinking that the warm, wet environment was mostly at the surface to thinking it was mostly in the subsurface, with limited exceptions," said co-author Scott Murchie of Johns Hopkins University.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.