Most common myths about the brain that are completely wrong

Nearly half of people with neuroscience degrees still believe these myths about the brain.

Are children more hyperactive after consuming sugary food? Is a common sign of dyslexia seeing letters backwards?

About 68% of people would answer yes to these questions. About 56% of teachers would agree, so do about 46% of individuals with a degree in neuroscience.

But they are wrong. These are two 'neuromyths' – widely held beliefs about the way the brain works that have no basis in evidence. They are incredibly common and believed even among people with training in neuroscience or education, according to a study in the journal Frontiers in Psychology.

"We were surprised at the level of neuromyth endorsement from respondents with neuroscience experience," said study author Lauren McGrath of the University of Denver in a statement.

"However, the myths they believed were related to learning and behaviour, and not the brain. So, their training in neuroscience doesn't necessarily translate to topics in psychology or education."

More than 3,045 members of the general public, 234 people with a neuroscience background and 598 teachers took part in the study. Other widely believed neuromyths include:

- Individuals learn better when they receive information in their preferred learning style

- People are either 'left-brained' or 'right-brained'

- We only use 10% of our brain capacity

- Listening to classical music makes children cleverer

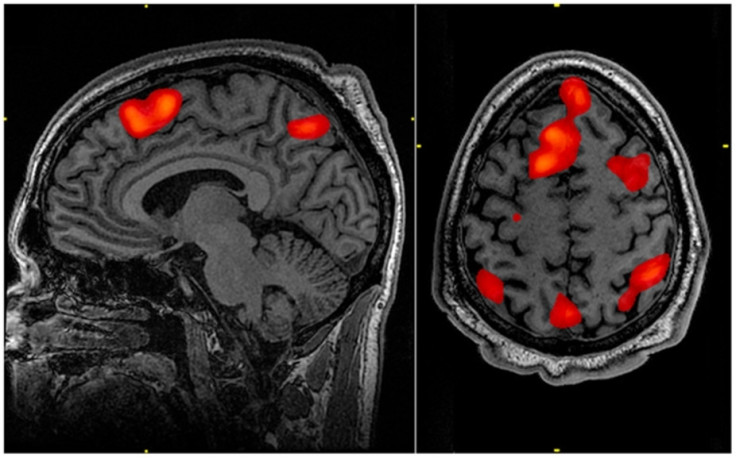

In fact, students do not necessarily learn best when taught in their preferred style of learning, either visual, auditory or kinaesthetic. The left-brain/right-brain belief is a broad generalisation from some lateralisation seen in neuroimaging studies. We employ a lot more than 10% of our brain on a daily basis for all kinds of conscious and subconscious activity. And listening to Mozart does not actually improve children's reasoning ability or make them cleverer.

If someone believed one of the neuromyths, they were very likely to believe in a whole host of others, the researchers found.

"We were surprised to see that these 'classic' neuromyths tend to cluster together, meaning that if you believe one myth, you are more likely to believe others," said McGrath.

The solution is not likely to be a simple one, the researchers say, as even neuroscientists frequently got the answers wrong. But for teachers at least, the solution could be simpler.

"We are considering an online training module for educators to dispel the most prevalent neuromyths. The fact that people tend to believe several myths means that training modules can't just teach about a single myth, they need to address several simultaneously."

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.