My South African Adventure: Eminem, Afrikaans Rapper Jack Parow and Kwaito Music

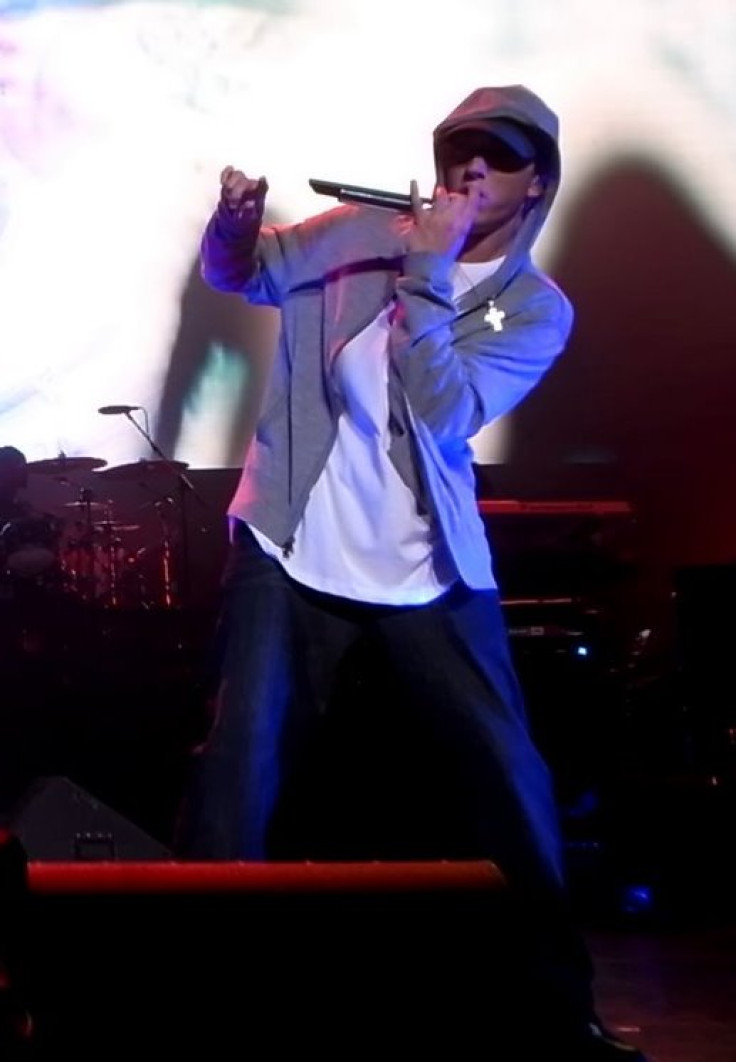

I don't really think Eminem is a stadium performer. I'm sure his zillions of fans out there will probably hate me for saying it, but to me he seems to be more of a dingy, smoky backroom-of-a-club kind of guy.

And that's not meant as a put-down. It's just that I think we're all better off playing to our strengths. And his, in my opinion, are his cleverly crafted lyrics and ability to share the often very personal details of his troubled life without descending into the mawkish or maudlin.

In fact, I'd say he's a true wordsmith. A bard of our times. But bards don't play stadiums – their performances are too intimate for that.

Another thing in my Eminem-not-being-suited-to-stadiums-view is that he's simply not got the stage presence of, say, a Bob Marley or a Freddie Mercury. His apparent reserve denies him that.

But he still puts on a good show, complete with plenty of stalking around the stage, overt tattoo-displaying and desolate-atmosphere-creation courtesy of a video backdrop showing lots of burning buildings, presumably in his home state of Michigan somewhere.

But my reservations notwithstanding, the Saturday night crowd of 60,000 packed into iconic rugby stadium, Ellis Park in Doornfontein, downtown Jozi, simply loved him. Which just goes to show what little I know.

But I must confess that the crowd wasn't quite what I'd expected either. In my day, which admittedly is a while ago now, you showed your allegiance to whichever subculture you were embroiled with by dressing in a certain, dare-I-say-it, rebellious fashion.

Whether you were into punk, Goth or Northern Soul, everyone could tell what your thing was by the way you dressed.

Never mind the irony that, with Eminem now hitting the grand old age of 41, we were probably closer to him in years than they were.

Not so with the concert-going youth of Johannesburg today though. While one or two deigned to attire themselves in time-honoured hip-hop fashion, most appeared tediously respectable in the careful homogeneity of well-cut jeans and freshly-laundered T-shirts.

But it seems that they were just as nonplussed by us. While admittedly we were probably twice the age of most of the souls there, my Beloved found himself accosted by young guys congratulating him on being old - not once, but twice.

"It's really great to see old people here," said the first without the tiniest hint of embarrassment as he muscled in at the bar and gave my Beloved a high-five. "It's really great to see old people out enjoying themselves."

The second bounced up to us just after the first support act in the shape of Afrikaner rapper, Jack Parow, had done his thing. "Great to see you here, man. You must be my parents' age. They'd never come to something like this – respect."

Never mind the irony that, with Eminem now hitting the grand old age of 41, we were probably closer to him in years than they were. But it must be said that, despite the prescription drugs and alcohol abuse, Marshall Mathers (aka Eminem) looked in much better nick that Mr Parow, also known as Zander Tyler to his mum.

A mere pup at the age of 32, Parow – so-called in honour of his working-class birthplace in the Western Cape – looked decidedly middle-aged, with his unclean-shaven fizog and beer belly pulling at his black T-shirt sporting the immortal words, 'Bitches Don't Know'.

Renowned for wearing baseball caps with ridiculously long peaks, Parow burst onto the South African music scene in 2009, rapping initially in English before riding the resurgent wave of interest in Afrikaans music and starting to perform in his native language.

Unlike the British word 'chav', 'zef' is used by members of the mostly white, lower-middle class subculture - who tend to be into souped-up cars and bling – with pride.

His rough-and-ready image and catchy tunes, meanwhile, are associated with a style of music known locally here as 'zef'. Roughly translated as 'common' in Afrikaans, the term is a shortened version of 'Ford Zephyr', which refers to a type of car popular among working-class South Africans for 20 years or so from the 1950s onwards.

Although calling someone 'zef' was initially an insult, the term has since been reclaimed. Which means that, unlike the British word 'chav', the term is used by members of the mostly white, lower-middle class subculture - who tend to be into souped-up cars and bling – with pride.

Another more widespread South African subculture that wasn't represented at the Eminem gig, however, was kwaito.

The most popular sound among the vast youth of the country's townships, kwaito was born in Johannesburg in the late 1980s when local DJs started remixing international house music tracks by slowing the tempo down and adding African rhythms and melodic percussion.

These rhythms included the marabi beats of the 1920's shebeen; the pennywhistle-based jives or kwela of the 1950s and the bubblegum disco sounds of the 1980s. Other influences include Jamaican dancehall, jazz and hip-hop, all coming together in a unique fusion.

However, things only really took off when self-professed 'king of kwaito', Arthur Mafokate, released his 1993 hit, 'Don't call Me Kaffir' - a degrading word for black Africans commonly used under the country's then crumbling apartheid regime.

Catching the mood of the time, it became the first song officially aired on the radio and kick-started a movement into the mainstream, which now sees kwaito being played all over the place.

Unlike its equally male-dominated cousin hip-hop, kwaito is a mainly - but not exclusively - apolitical style of dance music based on rhythmic speech. And, unlike rap, it tends not to have the same gangster-ish edge.

Although both genres reflect life in their respective ghettos, comprising both a fashion statement and lifestyle, it's as if the youth in South Africa just got sick of the intensity associated with the liberation struggle and decided to go down the let's-have-fun route instead.

One thing that's worth noting though is that, as the voice of modern urban life in the townships, kwaito isn't usually performed much in English. Instead it's based around Zulu, Sesotho and the local Sowetan street creole, Isicamtho, or Ringas, spoken by an estimated 500,000 young people as their primary tongue.

Zola, Boom Shaka and Mapaputsi remain major players in the scene, while more recent additions include Mandoza and the controversial Brickz.

Given kwaito's status as South Africa's second most popular type of music behind its world-renowned gospel choirs though, it just goes to show that playing to large stadiums isn't the only way to make it big.

Cath Everett, a resting journalist who has written about business, technology and HR issues for over 20 years, relocated from the UK to South Africa with her husband

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.