Mystery geographic tongue condition explained by physics

A mystery condition where map-like shapes appear on the tongue has been explained – in part – by physicists looking at the development of the condition.

Geographic tongue (GT) affects about 2% of the population yet little is known about the condition – including the exact cause.

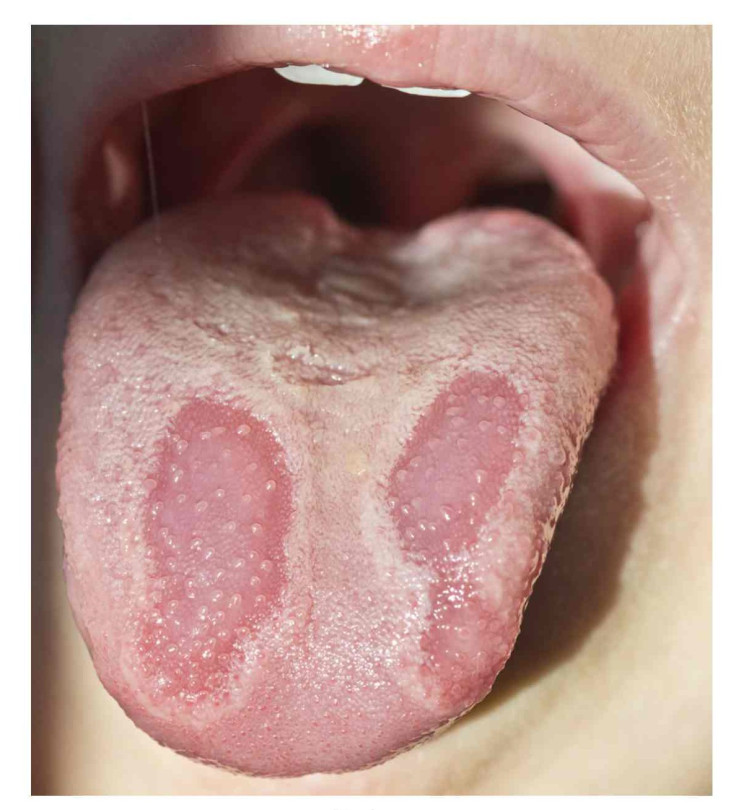

It is characterised by evolving red patches on the surface of the tongue that can look like a map. In some cases they appear as lines or spirals, in other large patches.

Scientists know that the patches appear as a result of the loss of one of four types of small hair-like protrusions on the surface of the tongue.

Researchers at the Weizmann Institute of Science in Israel decided to look at GT as if it was an "excitable medium" – where a wave can pass across, but the area cannot support the passing of another wave until a certain amount of time has passed.

An example of this is a forest fire – it can spread through a forest but cannot go back to a burnt spot until the vegetation has had enough time to regrow.

The study, published in the New Journal of Physics, found that GT spreads across the tongue in two ways. In one, it starts as small spots on the tongue then gradually expands in circular patterns until the whole tongue is affected, after which it heals itself. In the other, spiral patterns can form and evolve into regions of the tongue that are still recovering, meaning it does not heal.

Researchers say their findings could be used to diagnose the severity of GT cases.

Lead author Gabriel Seiden said: "While the propagation of small, circular lesions results in the whole tongue being gradually affected and subsequently healed, the propagation of spiral patterns involves a continuous, self-sustaining excitation of recovering regions, implying a more acute condition that will linger for a relatively long period of time.

"We hope these results can be used by physicians as practical way of assessing the severity of the condition based on the characteristic patterns observed."

Researchers also believe their findings could lead to a greater understanding of the causes of GT and they plan to collaborate with dentists and physicians to get data about the evolution of the condition.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.