Nasa's Cassini plunges into Saturn, ending its extraordinary mission after 20 years in space

The pioneering spacecraft has revolutionised our understanding of the solar system.

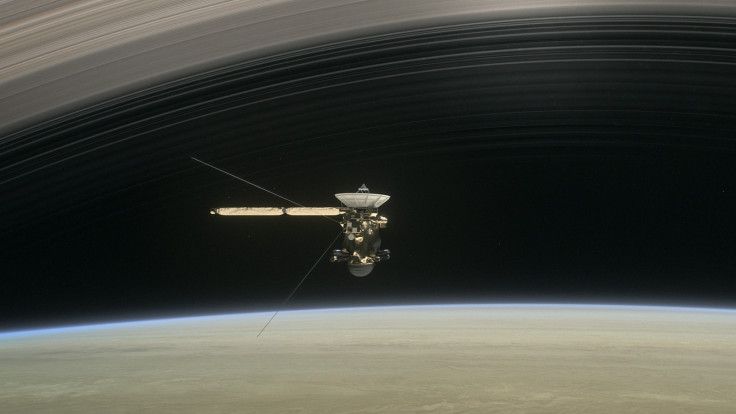

Following its 20 years in space, scientists around the world watched on as Nasa's ground-breaking Cassini spacecraft completed its mission in the most spectacular of ways, plunging itself at speeds of more than 100,000 kilometres per hour into Saturn's atmosphere to meet its fiery end.

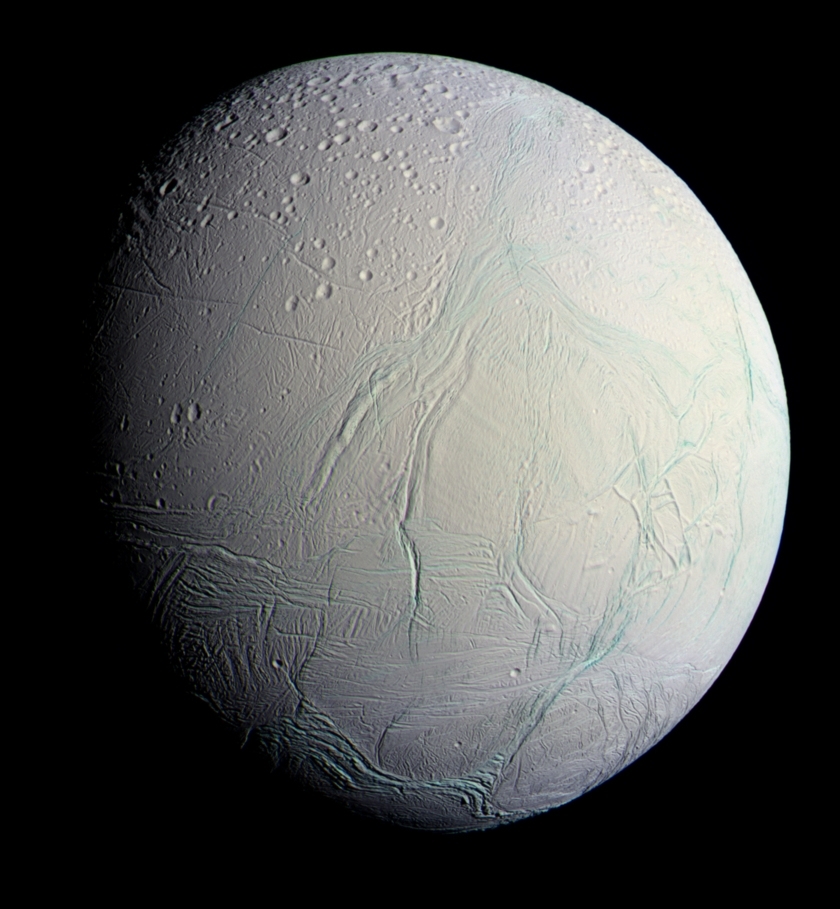

With its fuel reserves spent, and to abide by international treaties, Nasa operators deliberately destroyed the probe to avoid the possibility that it would one day crash into one on Saturn's many moons while stuck in orbit, contaminating pristine environments that could conceivably harbour life.

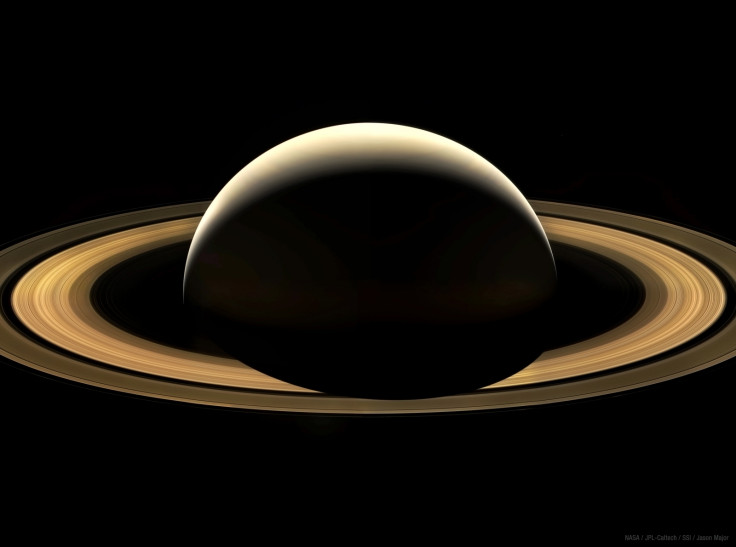

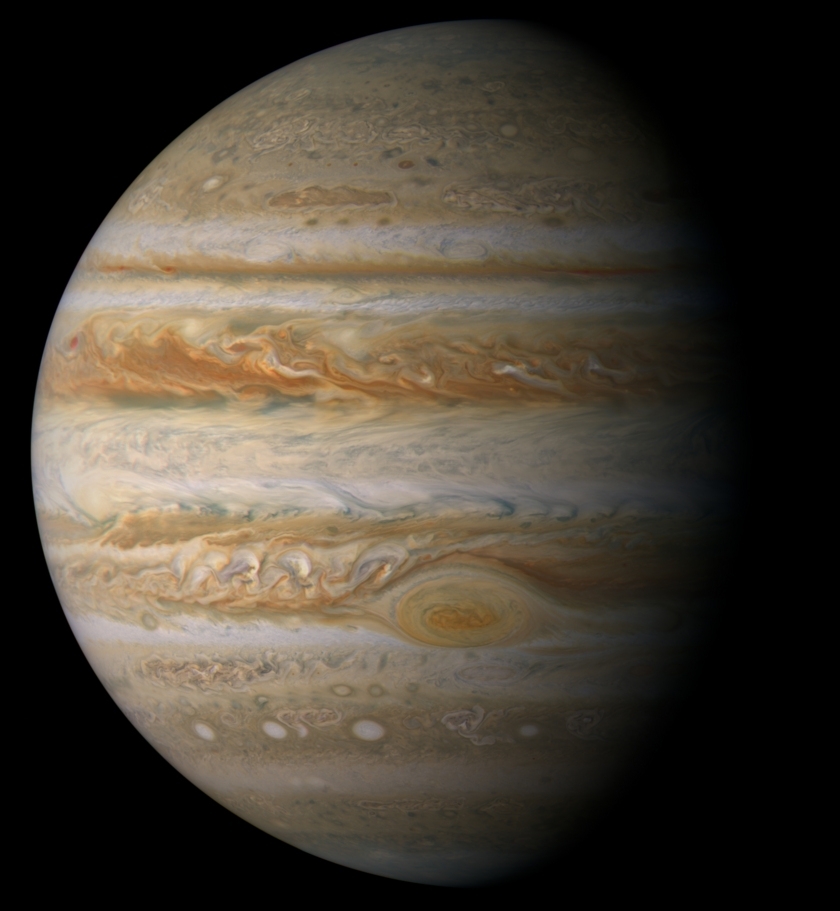

Cassini launched in 1997 and reached Saturn in 2004 with the help of carefully planned gravity assists, flying by Earth, Venus and Jupiter on its journey. It became the first spacecraft to enter Saturn's orbit. Over the course of its 13-year tour of Saturn, it has provided us with countless fascinating insights, revolutionising our understanding of the gas giant, its majestic rings and its 62 satellites.

For Todd Barber, Cassini propulsion lead engineer, who was at the controls for Cassini's tricky entry into Saturn's orbit, the highlights of the mission are nearly impossible to list:

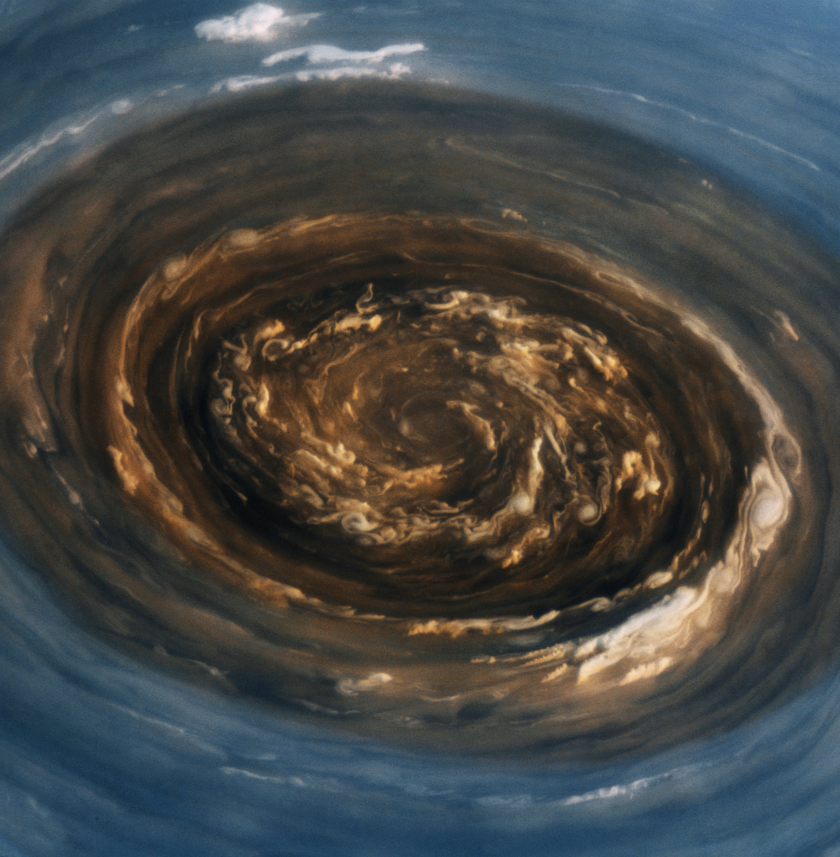

"The discoveries of six new Saturnian moons, a new ring of Saturn, icy geysers on Enceladus, liquid methane and ethane seas on Titan, irregularly shaped ring moons such as Pan, the north polar hexagon on Saturn, and bizarre structures within Saturn's rings are just a few of the items of note", Barber told IBTimes UK.

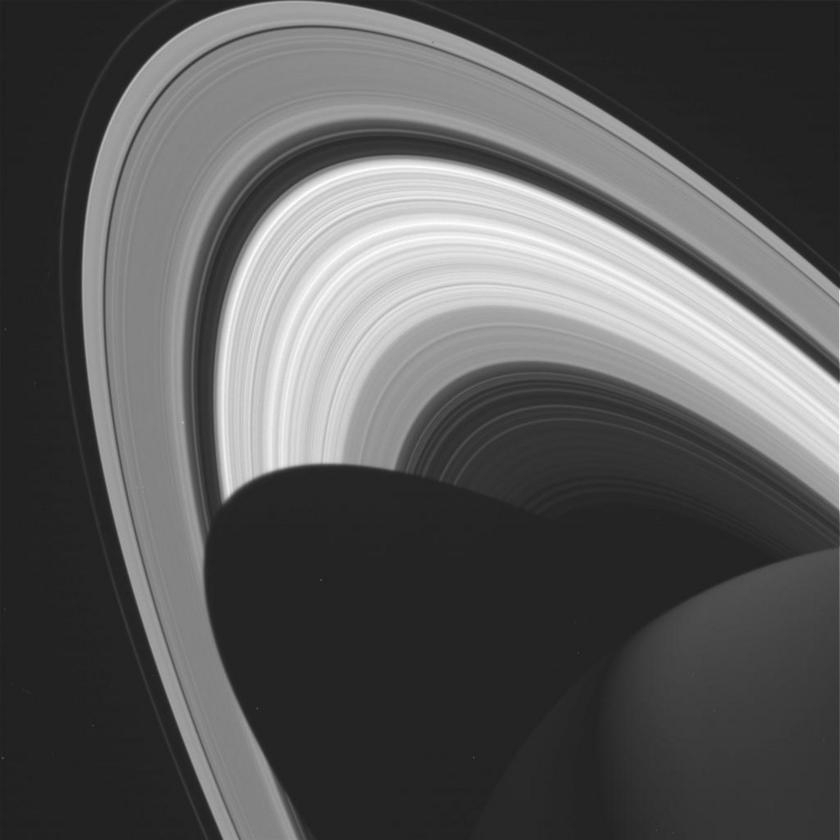

Furthermore, Cassini has shone a light on the long-debated question of the age of Saturn's rings, which measure 175,000 miles across and consist of rocks and moonlets as large as Mount Everest.

University of Colorado Professor Larry Esposito, who has been studying the rings since 1979, thinks they may be as old as the Solar System itself – around 4.6 billion years.

"When the two Voyager spacecraft passed by Saturn in 1980 and 1981, we thought the rings were relatively young," Esposito said. "But data from Cassini are consistent with the picture that Saturn has had rings throughout its history.

"We see extensive, rapid recycling of ring material in which moons are continually shattered into ring particles, which then gather and reform moons. They are renewed continually, so the rings themselves can be ancient, but the structures we see today are just part of their current manifestation."

"Seeing the rings of Saturn changing before our eyes" was one of the stand-out aspects of the mission Esposito told IBTimes UK.

In its last days, Cassini took some final images of the Saturn system, including the highest-resolution images to date of Saturn's rings.

Perhaps most intriguingly, Cassini has opened our eyes to the tantalising possibilities of life outside our planet. We now know for example that the tiny moon Enceladus with its interior ocean of liquid water and favourable chemical processes may be one of the best places to look for life beyond Earth.

"I think the main significance of the Cassini mission is that our preconceived notions about habitable worlds – i.e., places where life could exist – were way too limited", Barber said.

"Cassini has shown us that subsurface liquid water ocean worlds exist, even 1.5 billion kilometres from the sun. Moreover, the magic three ingredients for life on Earth – liquid water, organic or carbon chain molecules, and a source of heat or energy – also exist in the Saturn system. This doesn't necessarily mean there is life on the moons of Saturn, but it has opened our eyes to the possibility that we may not be alone, even in the solar system."

The Cassini mission also involved landing a probe – known as Huygens – on the giant moon Titan. This was the first successful landing in the outer Solar System, a feat that has not yet been beaten. Huygens separated from the main Cassini spacecraft in 2005 and still lies on Titan's surface, although it is no longer operational.

Even in its death throes, Cassini beamed backed data taken directly from the uppermost layers of the Saturn's atmosphere, something which has never been done before. This has provided scientists with a unique opportunity. As the information is analysed in the coming weeks, researchers will hope to gain new insights into the planet's formation and evolution, and the processes occurring in its atmosphere.

The descent "may well offer our best chance to characterize the interior structure of Saturn, the age of the rings, and the length of Saturn's day", Barber said. "More directly, we will obtain our best sampling of Saturn's atmosphere, helping us determine the hydrogen/helium ratio - important for understanding the origin of the solar system - and the chemical composition of Saturn's upper atmosphere.

As planned, Cassini entered Saturn's atmosphere just a short time ago. As it descended, the control thrusters worked furiously to keep its antenna pointed back to Earth so that it could relay the final precious data. Past a certain point though, the thrusters could do no more, and the craft began tumbling uncontrollably into the abyss, most likely burning up like a meteor.

Because of the vast distance between Saturn and Earth, the final radio signal took around 83 minutes to reach us, despite travelling near the speed of light. Nasa announced the transmissions had been received by its Deep Space antenna complex in Canberra at 11.15am GMT, tweeting: "Cassini is now part of the planet it studied. Thanks for the science #GrandFinale".

Confirmation of the last transmission prompted subdued applause from an emotional gathering of scientists at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in California where the Cassini control room is situated. Some of those working on the project have been involved for more than two decades.

Candy Hansen, a Senior Scientist at the Planetary Science Institute, who began working on Cassini 27 years ago, described this as a "bittersweet time".

"I feel sadness at losing the spacecraft, which now feels like an old friend, and satisfaction with the beautiful collection of data we managed to collect over the last 13 years", she told IBTimes UK.

Barber echoed her sentiments.

"It is a definitely a time of mixed emotions, with unquestionable poignancy and a bit of sadness as the spacecraft nears the end of its life. However, I think there is also a great deal of pride and a sense of accomplishment for a job well done. Cassini has outlived all expectations, and carried out ground-breaking science up until the last possible second. I can't imagine a better legacy for the spacecraft — or the mission — than this."

The legacy of Cassini will certainly live on through future scientific ventures. Already the lessons learned from the mission are being applied to the planning of Nasa's Clipper project, set for launch in the 2020s.

Clipper will fly by Europa - Jupiter's icy moon - to investigate its potential habitability using gravitational assists from the other moons to manoeuvre the craft into repeated close encounters with its target, a trick copied straight from Cassini. Knowledge from Cassini will also enhance Clipper's investigations and the methods it uses to collect data.

Nasa is also mulling over potential missions to Enceladus, to investigate signs of life there and to Titan, to explore its mysterious methane oceans.

"Cassini may be gone, but its scientific bounty will keep us occupied for many years," Linda Spilker, Cassini project scientist at JPL, said. "We've only scratched the surface of what we can learn from the mountain of data it has sent back over its lifetime."

"Things never will be quite the same for those of us on the Cassini team now that the spacecraft is no longer flying," said Spilker. "But, we take comfort knowing that every time we look up at Saturn in the night sky, part of Cassini will be there, too."

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.