New understanding of how HIV evades immune system paves way for new treatments

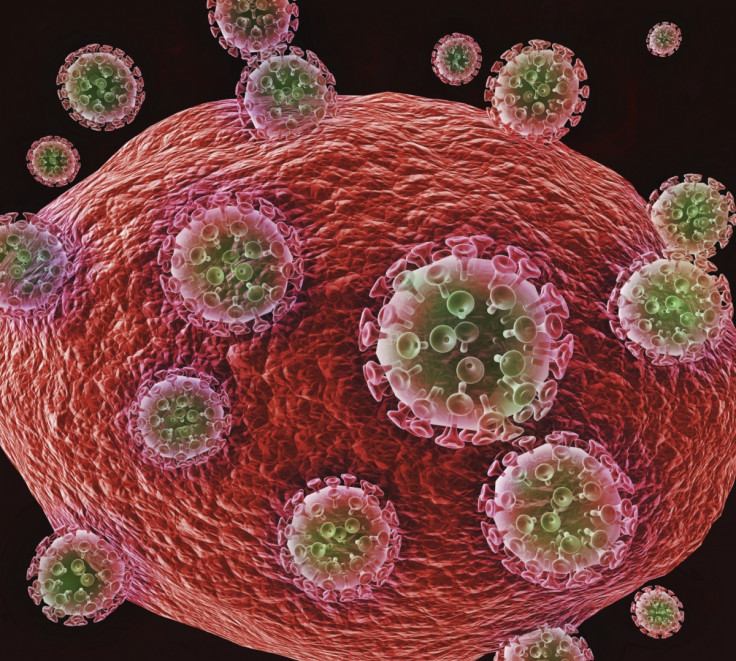

A protein surrounding the virus protects it in an original way from the host's immune system.

Scientists have discovered a new feature of the HIV virus that explains how it is able to infect human cells while avoiding detection by the immune system. The findings have triggered hopes that new drug targets can be found and that current treatments can be improved.

HIV is a retrovirus, characterised by the fact it has to copy its RNA genome into DNA when it integrates the host's DNA genome. The study, published in the journal Nature, focuses on the structure of the HIV virus and how it builds the DNA it needs to infect cells.

In particular, scientists have been struggling to understand how it acquire the nucleotides – building blocks of DNA – necessary to do so, and how come the immune system does not detect this foreign DNA in the body.

The study reveals a unique role for the protein shell known as capsid which surrounds the virus. The capsid is described as offering a protection to HIV as it integrates the DNA of the host's cells. According to the scientists, the way this protein functions may also explains why HIV is so successful at evading the immune system.

Intriguing iris-like capsid pores

The scientists, from the Medical Research Council and University College London, have conducted an in-depth observation of the capsid surrounding HIV. They looked at the protein's atomic structure in different states and also created mutant versions of HIV viruses, with altered capsids, to assess how infection was impacted.

This method allowed them to discover intriguing iris-like pores in the capsid which they had not identified before. Like the iris in the eye, these pores were able to open and close. They opened up to suck in the nucleotides needed for replication of RNA into DNA and closed to leave out any unwanted molecules – making sure the virus was not exposed to the immune system's molecules.

This finding is interesting because it represents a new drug target for scientists to come up with novel HIV treatments. In fact, the research team designed an inhibitor molecule – called hexacarboxybenzene – to block the action of capsid pores. In lab settings, this led to the HIV virus becoming unable to copy itself, and thus to lose its infectious properties.

This demonstrates the importance of capsid pores as a drug target in future HIV treatment research. The problem is that hexacarboxybenzene cannot cross the cell membrane of human cells to reach the virus so it cannot be used as the basis for a treatment.

Nevertheless, the researchers believe that drugs could soon be designed with similar properties and an ability to enter human cells. Examining how current treatments could be improved to target the capsid pores could also be an option.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.