In pictures: 'Butcher of Bosnia', siege of Sarajevo and Srebrenica massacre

The UN tribunal on war crimes in former Yugoslavia has convicted General Ratko Mladic of crimes against humanity and genocide during Bosnia's 1992-95 war.

The UN tribunal on war crimes in former Yugoslavia has convicted General Ratko Mladic of crimes against humanity and genocide during Bosnia's 1992-95 war.

The former Bosnian Serb military chief has been sentenced to life imprisonment for commanding forces responsible for the deadly three-year siege of Sarajevo and the 1995 massacre of some 8,000 Muslim men and boys in the eastern enclave of Srebrenica, Europe's worst mass killing since the Nazis in World War II.

The court in The Hague convicted Mladic of 10 of 11 counts in a dramatic climax to the effort to seek justice for the wars in the former Yugoslavia. Presiding Judge Alphons Orie read out the judgment after ordering Mladic out of the courtroom over an angry outburst.

The conflict erupted after the breakup of the former multi-ethnic federation of Yugoslavia in the early 1990s, with the worst crimes taking place in Bosnia. More than 100,000 people died and millions lost their homes before a peace agreement was signed in 1995.

The "Butcher of Bosnia" to his enemies, Mladic is still seen as a national hero by compatriots for presiding over the swift capture of 70 percent of Bosnia after its Serbs rose up against a Muslim-Croat declaration of independence from Yugoslavia.

The siege and bombardment of the Bosnian capital Sarajevo killed 10,000 civilians. The prosecution described it as a plan to "spread terror among the civilian population". Mladic's lawyers had argued that Sarajevo was a legitimate military target as it was the main bastion of Muslim-led Bosnian government forces.

Early in 1993, Serbs started an offensive on Muslim-held areas. The towns of Srebrenica and Zepa became isolated enclaves deep in Serb-held territory. Muslims from the area flocked to Srebrenica and the population swelled to 60,000. They had little food, water or medical supplies.

In April, Srebrenica, Zepa and Gorazde in eastern Bosnia were declared three of six UN 'safe areas'. The United Nations Protection Force deployed troops and the Serb attacks stopped. However, the town remained isolated and only a few humanitarian convoys reached it in the following two years.

Then-Bosnian Serb President Radovan Karadžić ordered that Srebrenica and Zepa be entirely cut off and aid convoys be stopped from reaching the towns.

On 9 July 1995, Karadžić issued a new order to conquer Srebrenica. Troops surrounded the enclave and attacked the observation posts of Dutch peacekeepers, taking about 30 soldiers hostage. The following day, Serbian forces started shelling Srebrenica. The Dutch threatened the Serbs with Nato air strikes if they did not withdraw by morning.

The next day Nato planes bombed Serb tanks outside Srebrenica. The Serbs threatened to resume shelling and kill the captured Dutch soldiers. Air strikes stopped and in the evening of 11 July, Bosnian Serb commander General Ratko Mladic entered Srebrenica.

An estimated 30,000 Muslim refugees packed around the Dutch peacekeeping base in Potocari, just north of Srebrenica, after Bosnian Serb forces seized the 'safe area'. Mladic was filmed visiting a refugee camp in Srebrenica on 12 July. "He was giving away chocolate and sweets to the children while the cameras were rolling, telling us nothing will happen and that we have no reason to be afraid," recalled Munira Subasic of the Mothers of Srebrenica group.

"After the cameras left he gave an order to kill whoever could be killed, rape whoever could be raped and finally he ordered us all to be banished and chased out of Srebrenica, so he could make an 'ethnically clean' city," she told Reuters.

Bosnian Serb forces put the frightened refugees on to buses to leave. Many of the refugees were evacuated to Kladanj, 30 miles away on the edge of government-held territory.

The UN noticed that most of the refugees arriving from Srebrenica were women, children, and the elderly and became concerned about the fate of the men.

Over the week that followed the fall of Srebrenica, a total of about 8,000 men and boys from the enclave are estimated to have been killed by Bosnian Serb forces in detention or while trying to flee through the woods.

Men were crammed into warehouses, schools and barns in the area outside Srebrenica. They were shot and their bodies were dumped in mass graves. Serb forces subsequently dug up the bodies and scattered them in a systematic effort to conceal the crime. UN war crimes investigators later excavated mass graves.

Identification of the bodies is difficult: bodies were broken up by excavators that bulldozed them into mass graves. Bodies were also moved from the original graves to secondary locations to conceal the crime. Forensic experts painstakingly work through what is left of the bodies found in the hundreds of mass graves that have been discovered in the area.

Every year on 11 July, the remains of those who have been identified over the past year are buried at the Memorial Centre in Potocari.

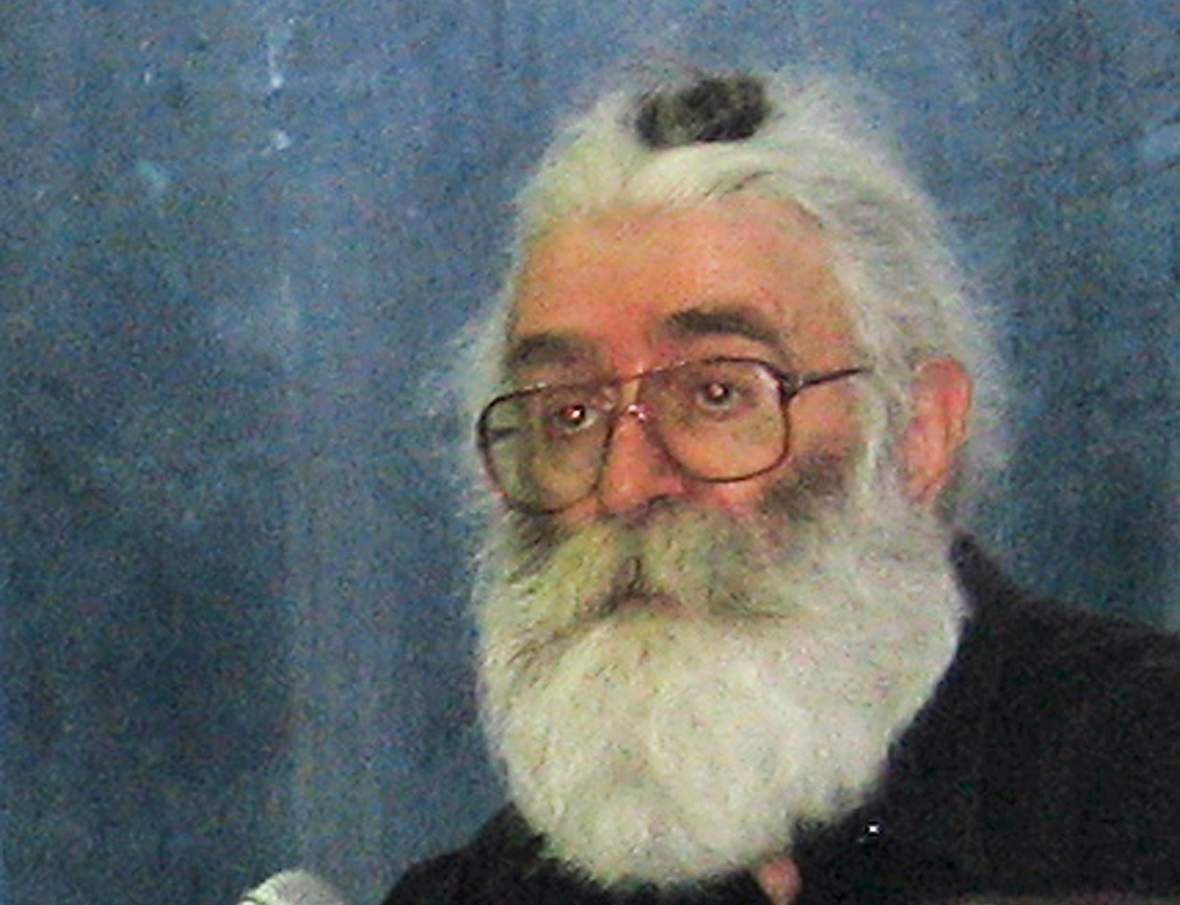

Karadzic was indicted in 1995 but evaded arrest until he was captured in Belgrade, Serbia, in 2008. At the time, he was posing as a New Age healer named Dr Dragan Dabic, and was disguised by a thick beard and shaggy hair.

Mladic evaded capture until 2011. His trial in The Hague took more than four years in part because of delays due to his poor health. Mladic has suffered several strokes, though UN judges rejected a flurry of last-minute attempts by defence lawyers to put off the verdict on medical grounds.

Most Serbs, both in Bosnia and Serbia whose 1990s leadership armed and funded Bosnian Serb forces, strongly deny that the massacre was genocide as judged by the UN war crimes tribunal for former Yugoslavia.

They dispute the death toll and the official account of what happened, reflecting conflicting narratives about how and why Yugoslavia broke up in bloodshed. That divide continues to hinder reconciliation and stifle Bosnia's progress toward integration with Western Europe. The Balkan country today is split into autonomous Serb and Bosniak-Croat entities.

In June 2017, a Dutch appeals court confirmed that the Netherlands was partly liable for the deaths in 1995 of some 300 Muslim males who were expelled from a Dutch UN base after the surrounding area was overrun by Bosnian Serb troops. The ruling by the Hague Appeals Court upheld a 2014 decision that Dutch peacekeepers should have known that the men seeking refuge at the base near Srebrenica would be murdered by Bosnian Serb troops if they were forced to leave – as they were.

The Dutch government resigned in 2002 after acknowledging its failure to protect the refugees, but it said then that the peacekeepers had been on 'mission impossible'.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.