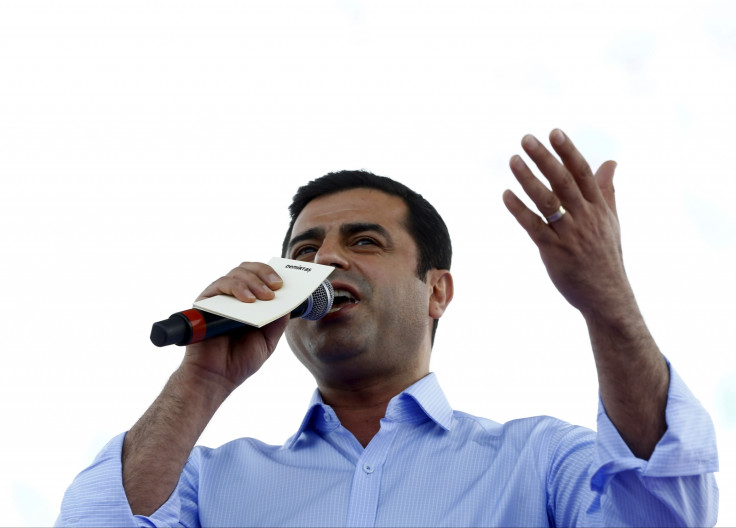

Selahattin Demirtas: Meet the Kurdish lawyer that could crush Erdogan's dreams

A Kurdish human rights lawyer from Turkey's remote southeastern region of Diyarbakir is set to pose an unprecedented challenge to the authoritarian regime of Recep Tayyip Erdogan at the upcoming parliamentary elections.

Selahattin Demirtaş, the 42-year-old charismatic leader of the liberal Kurdish platform of the People's Democracy Party (HDP) is widely hinted to be the only man who could counteract Erdogan's gargantuan ego and ambition. Eloquent, young, telegenic - to many commentators Demirtas reminds of a younger, less arrogant version of the Turkish president.

"Demirtas gained a vast popularity in recent weeks for his ability to stand up to Erdogan, deal with him on a rhetorical level," Ege Seckin, analyst at IHS, told IBTimes UK. "His winning points? He's a very good speaker and his political capabilities have proven to be a good match against Erdogan, a political mastermind."

Erkan Saka, who teaches at Istanbul's Bilgi University, said Demirtas is key to HDP's grassroots campaigning that attracted many volunteers all across the country. "He's a good communicator, sometimes I think of him as Erdogan in his early years but with a basic difference: Erdogan is more aggressive and unifying, while Demirtas uses political humour to address his policies."

Last year, Demirtas challenged Erdogan at the presidential elections, receiving 9.8% of the vote. His HDP party needs to pass the threshold of 10% of votes - a measure introduced in the 1980s to keep the Kurdish parties out of the political arena- to enter parliament. There are up to 70 seats at stake, enough to prevent Erdogan's AKP (Justice and Development party) from getting a two-third majority allowing them to rewrite the constitution.

The fumbling president, who has dominated Turkish politics for 12 years after being elected prime minister three times, plans to abolish parliamentarianism and turn the Turkish democracy into a powerful executive presidency led by himself.

But his rampant authoritarianism, the ruthless repression of Gezi Park protests in 2013 and the relentless crackdown on human rights and freedom of expression have increasingly alienated more than half of the Turkish population.

In this contest, the HPD broadened its appeal in recent months beyond its Kurdish core constituency, Seckin explains, in an effort to catch votes from Turkish liberals but also the Allevi sect, which constitutes about 15% of the population.

"The HDP has done a lot in the past weeks to present itself as a peaceful and liberal party, which champions human rights and fills a gap in Turkish political landscape," Seckin said. "One of HDP's senior representatives took part in the Gezi protest, was one of the leading figures. It is a bottom-up movement."

For the first time, many people who traditionally voted for the CHP, the party founded by the founding father of modern Turkey Mustafa Kemal Ataturk, are ready to tactically switch vote for the HDP.

Feeling the pressure, AKP representatives have been hysterical in trying to persuade Turkish people not to vote for the HDP and smear their image. Erdogan himself, who is not even running for election, has ranted against Demirtas dubbing him as someone "who stands behind the terror organisation" and a puppet of the jailed leader of the Kurdistan Workers Party (PKK) Abdullah Ocalan.

Interestingly, Demirtas has never denied meeting Ocalan in jail for advice, highlighting instead the discrepancy between 12 years of government's policies in favour of the Kurds and the anti-Kurdish rhetoric of the electoral campaign. Since 2002, Kurdish-language television and school classes have been greenlighted by the Erdogan's government. Ten years after, the government officially began talks with the PKK.

Erdogan's party is the second most popular in the Kurdish southeast region, but the recent hawkish rhetoric of the flamboyant Turkish president risks compromising the support in the area.

"The AKP is in a really delicate situation," Seckin said. "The AKP made a lot of concessions on the PKK peace process and that will award the nationalist party [MHP]. That's why Erdogan intensified the anti-Kurdish rhetoric in the past months."

If the HDP fails to enter parliament, the AKP will gain seats from the party, emboldening Erdogan's plans for a presidential reform. Ayse Erdem, the HDP's co-leader in Istanbul told the Guardian that they "fully expect that there will be attempts at cheating". Accusations of vote-rigging tainted last March's municipal elections and opposition activists fear government supporters will try to switch the thousand votes needed to secure an AKP majority.

Citizens group are organising to carry out their own monitoring. But experts warn that if the HDP is excluded from the parliament, Erdogan opposers are ready to take to the streets in a nationwide protest that could rival Gezi Park in 2013.

"I will not be surprised to see a movement similar to Gezi, involving a wide social spectrum: secular people, Muslims, urban and countryside, middle-class and working class people," Seckin said. "Around 50-55% of the country's population is entirely opposed to Erdogan. That has always been the case."

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.