Why some banks and governments still stifling the mobile money inclusion miracle

Africa has shown how mobile money including mobile payments can perform miracles in terms of financial inclusion but a number of banks and governments still cling to a monopoly in some places by maintaining outdated legislations and regulations.

This important topic kicked off London's Fintech Week, courtesy of a presentation by mobile payments and telecommunication strategy and regs expert Jean-Stéphane Gourévitch analysing some strategic and policy developments in mobile money, mobile payments and mobile banking in both developed and emerging countries.

J-S. Gourévitch acts as an independent consultant in the space of convergence, digital payments and mobile payments and also as a mentor to startups like M-Changa in Kenya, Loot App and Startupbootcamp Fintech finalist Tradle.

"When you look around the world you see that countries that have decided to maintain a monopoly from banks or have bank-led models have seen a very poor growth of mobile money in their region.

"Countries that have pushed a mixed model or an open model where any provider including mobile operators is able to provide mobile money directly, provided they obtained the necessary regulatory registration or licence, the growth rate is extraordinary," said Gourevitch.

India

An interesting example is India. Up until last year India had a very restrictive regulatory framework, reserving the possibility to provide mobile money to banks. They even went a bit further by forcing mobile operators to give access to the Unstructured Supplementary Service Data (USSD) channel.

USSD is a protocol used by GSM cellular telephones to communicate with the service provider's computer. It runs on 2G networks and is a channel that is owned by the mobile operators and used normally to refill their customers' prepaid cards.

But this can also be used to provide financial services, mobile financial services and transactions.

"In a number of countries – India being one – the banks have lobbied the governments to impose mandatory access for non-mobile operators to this channel on the mobile network," noted Gourevitch.

The government also imposed a price cap on accessing this infrastructure as well as a rigid determined pre-conditions.

The result was that the gross rate of mobile money in India reached 0.2% last year. Luckily for the country's population this situation is changing.

Under the influence of the new government, prime minister Narendra Modi and the new governor of the central bank, India has adopted a new regulation, creating what are called payment banks.

The legislation came into force in January 2015. India recently granted 19 licences including a number of them to the main mobile operators such as Vodafone, Bharti Airtel, etc.

"You can expect India to be really lifted now and you will see a meteoric rise of mobile money in India; the government is putting a lot of emphasis on mobile money as a way to fight for financial inclusion," said Gourévitch.

China

China is another interesting example. A number of new players, including web commerce giant Alibaba, have been entering deeper and deeper into financial services.

This trend was initially encouraged by Chinese authorities, who pushed for these players to acquire banking licences last year.

But it came to a point where they became so popular and mobile payments grew so much that they became serious competitors to the banks.

"Very recently the People's Bank of China adopted a very restrictive legislation on mobile payments that curtailed the amount you can transact from your e-money account, put some caps etc, all that in order to slow down the growth of mobile payments in China," said Gourévitch.

Africa

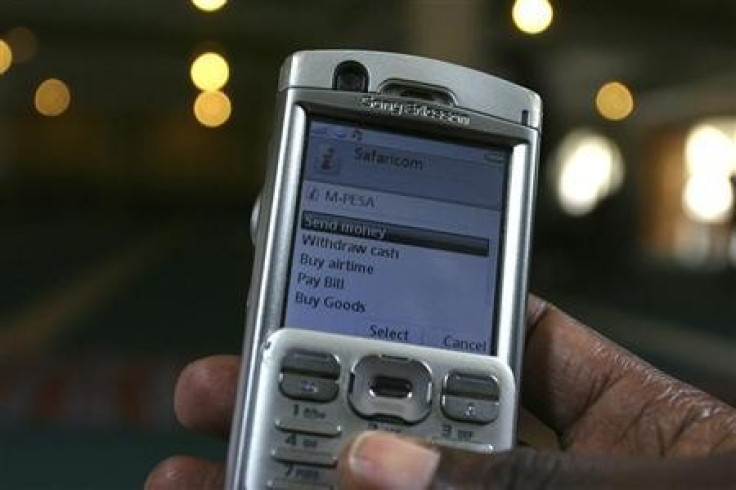

Mobile money in Africa is one of the great digital success stories of our time. There is a tendency to reduce this to Kenya and the iconic M-Pesa brand created by Safaricom partially owned by Vodafone, but leapfrogging is happening elsewhere in the continent and with other operators.

'I know that people in Africa are unhappy when M-Pesa is the only company that is referred to – there are others that have done some fantastic things, particularly MTN, Orange, Millicom's Tigo, Ecocash. For a long time, mobile money didn't pick up as much in Western Africa than it did in Eastern Africa that benefited from the alignment of positive stars including Central Banks ready to trial new developments without imposing immediately heavy banking regulations, innovative mobile operators, high mobile penetration " noted Gourévitch:

But the M-Pesa story is worth recounting. Mobile money represents 60% of the Kenyan GDP today. In some areas in Kenya the use of mobile money meant that people were going to increase their monthly disposable income from 5% to 35%. The more remote the place, the more pronounced the growth in income, simply because people no longer have to travel to the next big city; they can spend their time more productively than queuing all day outside banks.

"We have seen some real successes particularly in eastern Africa. Tanzania is another example of incredible developments in the field of mobile money.

"However, northern Africa is a desert in terms of mobile money. Apart from Egypt there is almost nothing happening in north Africa.

"And it's very strange in a way because the needs are there, the needs are the same. You have a lot of unbanked people; you have a lot of poor people lacking access to financial services, so clearly there is a problem.

"One of the bottlenecks probably is linked with the political and regulatory scenes. Western Africa had a very poor growth rate for mobile money for a long time, but since last year, particularly inIvory Coast or Ghana, you have an incredible take up."

There has lately been more competition and mobile financial services in places like Africa have become more sophisticated.

What started as peer-to-peer money transfer or remittance has evolved in to a very complex ecosystem, with savings, mobile insurance and mobile credit.

"Safaricom's M-Pesa developed with Commercial Bank Of Africa – something called M-Shwari that is an extraordinary proposition, which actually would be very useful in our developed countries for people that are unbanked or experiencing major financial woes," noted Gourévitch.

Existing M-Pesa customers with a good track record and payments history can access relatively cheap short term loans, usually with an interest rate of around 6-7%.

"Compare that with Wonga. When you start to reimburse, a large part of the reimbursement is actually going to a saving account.

"If you are correctly reimbursing, you are rewarded by the fact you are saving money. This is very popular in Kenya. The uptake and usage of M-Shwari in the past two years has been remarkable. There are over 10 million M-Shwari accounts and CBA disburses 50,000 loans every day. One-third of all active M-PESA users are also active M-Shwari customers."

"In a number of countries in Africa and Asia you can also pay directly your rent to your landlord, you can pay utilities, proceed to a number of banking operations, saving, even insurance through your mobile – it's not just transfer or remittance anymore but a more sophisticated financial services ecosystem and in some respect more advanced than in developed countries. Traditional collective management of money and fundraising practices that exist since hundreds of year combine with digital technology and allow development of crowdfunding and fundraising on mobile platforms (see M-Changa in Kenya but also the very recent announcement by Orange that the operator will enable crowdfunding products on its Orange Money, mobile money platform in West African countries in its footprint, in particular Ivory Coast."

Operators like Millicom's Tigo have been highly innovative in Africa and Latin America. For instance, in Tanzania they managed to obtain approval from the central bank to actually redistribute to their customers the interest accrued on the segregated accounts they have to maintain for regulatory purposes where they have to keep the money corresponding to the e-money they are issuing.

"They have returned this interest, which represents a good couple of millions to their customers," said Gourévitch.

People trust their telcos in these countries more than banks in many instances and only 20% of African people for instance holds a bank account whilst 80% holds a mobile account IN Sub-Saharian Africa. They have seen the investment telcos made in infrastructure, and now they are seeing innovation that also does them good.

The rule in Africa is that one size does not fit all. The growth and development of mobile money is very much related to the mix of local cultural, regulatory, social conditions.

Even the weather can play a part, said Gourévitch.

"Weather patterns can influence whether it's possible or easy to provide mobile money because you are using frequencies and when you have monsoon rains or certain type of weather patterns, it creates interference so it is difficult to have any form of communication ."

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.