Syriza elections victory: Does the eurozone need Greece?

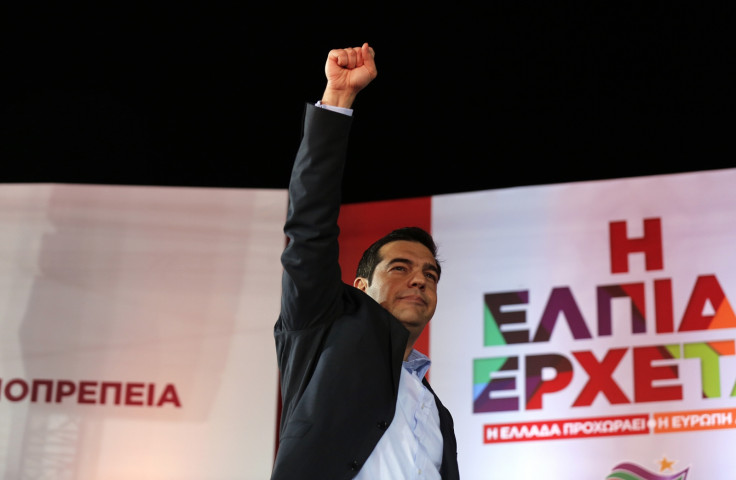

Alexis Tsipras wants to stay in the eurozone, but he has a funny way of showing it.

The leader of the radical left Syriza party and new prime minister of Greece has declared his electoral victory as an "end to austerity" in the country and the death of the Troika of lenders, whose bailout loans rescued it from bankruptcy at the height of the eurozone crisis.

Tsipras is confident of his position. He believes in his mandate from the Greek people to fight the Troika and the austerity it demands of Greece in return for loans by renegotiating their exacting – but, many argue, inescapable – terms. He even threatened a Greek default.

And he believes the eurozone has little choice but to negotiate on his terms because it has so much political capital invested in keeping Greece inside the single currency area.

There are similar anti-austerity rumblings elsewhere, such as Spain where the radical left party Podemos is polling first ahead of the elections later in 2015.

"This is absolutely not just a Greek affair. The rest of Europe is watching," Vincenzo Scarpetta, policy analyst at the Open Europe thinktank, told IBTimes UK.

"Any significant concessions made to Greece will mean that other countries will come knocking and demand the same treatment.

"Whichever way the negotiations go, Greece will be a testing ground for the future of the eurozone."

Posturing

The €240bn (£180bn, $270bn) of loans from the Troika – the European Union (EU), International Monetary Fund (IMF) and European Central Bank (ECB) – came with strict terms.

Greece has had to cut deeply into its public spending in order to bring government finances back into check after they spiralled so far out of control, as well as make fundamental liberalising reforms to its state-dependent economy.

These have meant financial pain for ordinary Greeks, who have seen unemployment spike, incomes drop rapidly and public services withdrawn, and led to the rise of Tsipras's radical anti-austerity party, Syriza.

Tsipras did not manage to win an outright majority of seats in the Greek parliament, falling just short. But a coalition with other anti-austerity elements in parliament will secure him a majority.

By the sounds of his forthright speeches, Tsipras believes he is in a strong position against the Troika and more senior eurozone member states, such as its largest economy, Germany. But is he?

Syriza wants a debt write down from the Troika. It also plans a big capital investment programme to stimulate the Greek economy, paid for in part by higher taxes on the wealthiest Greeks. This, it believes, is the way to erase the deficit – by growing the economy.

But its critics say this is unrealistic. Wealthy Greeks will move their money offshore, if they haven't already. And more public spending isn't sustainable because it will mean more borrowing from the bond markets at the large interest rates Greece already cannot afford to pay.

Austerity and economic reform, they argue, are inevitable so it's better to get the pain out of the way as quickly as possible.

While Tsipras demands an end to austerity and debt write downs for Greece, the Germans say no, this is not possible.

The most Germany and others are willing to offer is a similar renegotiation to 2012, which involved extending the maturity of Greek date and cutting interest rates on outstanding debt.

"At the moment I think we are still at posturing stage because the negotiations haven't started yet," Scarpetta said.

"The negotiations will no doubt be different this time around because the room for compromise has narrowed, especially now that Syriza has entered a coalition with another strongly anti-bailout party, the Independent Greeks. So they will adopt a tougher stance."

Hardball

Both sides have their strengths. The Greek economy has a primary budget surplus and the banking system is stronger than it was, less reliant on the Greek central bank and ECB for liquidity. A Greek exit from the eurozone would be painful, but less so than before.

And the eurozone has built up systems to help it cope with a renewed financial crisis, perhaps sparked by a Greek exit. The entire system is far more robust. In economic terms, the eurozone doesn't need Greece to stay.

"So both sides have the incentive to play hardball in the negotiations," Scarpetta said.

"Which doesn't mean we should rush to rule out a compromise, because if you remember in 2012 many analysts were predicting a Greek exit from the eurozone. What happened next? They just struck a deal.

"The fact is it's not particularly clear what that compromise would involve. I can see a bit of a Catch-22. Anything short of a write down of Greek debt is likely to have limited impact.

"But a serious debt write down seems to be off the table. It has been ruled out by the German government. At this stage it looks hard for the IMF and the ECB to renegotiate €52bn of Greek debt they hold at the moment in total between the two."

He added: "We should not forget that Tsipras has been promising big during the election campaign. So now the expectations in people who voted for him are running very high. This is the reason why we think the negotiations will be different this time around. Compromise is still possible, but it would involve one of the two sides taking a big step backwards."

Anti-austerity contagion

The eurozone is in a difficult position. Its leaders and proponents have long said that eurozone membership is permanent and irreversible. It is much more than a currency bloc. It is a political project to foster closer union within Europe.

"Obviously if one country were to leave the eurozone, the myth of the irreversible single currency would be bust. It would be gone forever," Scarpetta said.

But many of the eurozone leaders see the radical left and anti-austerity populism as a fundamental threat to the project. This is because in order for the eurozone to be sustainable, all member states must reform their public finances and liberalise their economies.

That means pushing the politically-difficult austerity programmes in the face of staunch opposition. Greece is the first state to buckle under the political pressure of austerity, where cuts have been the deepest.

The Troika rowing back on austerity and reform would show other states grappling with similar problems and their electorates that alternatives are possible, incentivising similar revolts elsewhere, such as in Spain with Podemos.

And there would be implications for the ECB's vast and expanding quantitative easing (QE) programme to buy hundreds of billions of euros' worth of eurozone sovereign debt in order to boost inflation above its near-zero rate and therefore spur on much-needed economic growth.

Germany has been cautious on such QE from the ECB because it is worried this will remove the moral hazard for eurozone countries when it comes to issuing their own debt. Bond-buying QE by the ECB – widely seen as necessary and late – will bring down borrowing costs for eurozone states.

So if there is a wave of anti-austerity feeling sparked across the eurozone by a relaxation of the terms for Greece, low interest rates on sovereign debt could lead to a borrow-and-spend frenzy at a time when fiscal restraint and restructuring are most needed, undoing years of work since the crisis.

"If Tsipras manages to extract significant concessions from the Troika, then this will bolster the capacity of similar left parties to win increasing support (all eyes are now on Spain, with Podemos looking strong ahead of the general elections at the end of the year)," said a research note from Bank of America Merrill Lynch.

"More moderate centre-left governments in France and Italy could then decide to embark on fiscal relaxation/renege on structural reforms, offering an alternative policy package to the Germany-inspired one which has so far dominated the adjustment.

"Then counting on Germany's tacit support for QE – Merkel has refused to criticise it directly in spite of a livid local press – for a second helping wouldn't be straightforward. That's the reason why the Europeans are likely to 'talk tough' to Greece in the next few months (while keeping the door open to some compromise).

"Even peripheral governments will be on this line (e.g. the Spanish government interest will be to demonstrate that the left wing approach to the adjustment cannot work). This will generate volatility, if only because the Europeans have their own hardliners to convince."

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.