Ukraine: Symbolic freedom fighter and filmmaker Oleg Sentsov languishes in Russian labour camp

This summer there were no Ferrero Roches in sight at the ambassador's sumptuous Holland Park residence in west London. Just a sombre air, yellow and blue everywhere you looked under the grand chandeliers; napkins, miniature flags, Alice bands, flowers and a patriotic gathering of young and old, nonetheless exuding pride at an independence day ceremony.

Ukrainians in London have kept the flag flying despite the simmering war at home in Donbas that has claimed thousands of lives and shows to signs of ending. A group of cultural ambassadors; actors, film producers and financiers arrived last week (10-13 December) to promote the country's film productions and change the way outsiders continue to perceive it.

I don't know what your beliefs can possibly be worth if you are not ready to suffer or die for them.

Pylyp Illienko, Head of Ukrainian State Film Agency, on the second day of his first visit to London to promote Days Of Ukrainian Cinema, a showcase for the country's latest film output, injects some comic relief into proceedings. "Mr Bean is bigger than James Bond in Ukraine," he says, making light of his country's taste in British movies.

Swiftly the topic moves to the case of incarcerated Ukrainian film director and international cause célèbre, Oleg Sentsov, sentenced to 20 years in prison by Russia for his outspoken comments on the annexation of Crimea and the civil strife raging in the Donbas region of Ukraine.

Illienko declares gravely: "[Russian authorities] use him as a hostage in this conflict between Russia and Ukraine. I am deeply shocked that this could happen in 21st century in Europe. This is absolutely something which cannot be tolerated that a person is imprisoned for more than 20 years for just being a citizen of Ukraine fighting for the freedom of his people. Not fighting as a soldier, he was fighting as a civil activist who took part in the events of Maidan and after the Crimea was occupied by Russia."

Sentsov's cause has continued to be championed by a group of European film directors, including Ken Loach, Mike Leigh and Wim Wenders, who signed an open-letter to President Vladimir Putin demanding his release.

He has also attracted support from celebrated Russian director Nikita Mikhalkov, who has close ties to President Vladimir Putin and has openly backed Russia's annexation of Crimea.

Ukrainian President Petro Poroshenko wrote on Facebook: "Hang on in there, Oleg. Time will pass, and those who organised this kangaroo court will find themselves in the dock."

He told the court he was tortured and threatened with rape or murder after his arrest in May 2014, to try force him to confess to a terrorist plot and implicate others – but he stood his ground.

At his trial in Rostov-on-Don, south-west Russia, he declared: "Treason and betrayal can sometimes start with simple cowardice. When they put a bag on your head, beat you up a bit, and half an hour later, you're ready to go back on all your beliefs, implicate yourself in whatever they ask, implicate others, just to stop them beating you. I don't know what your beliefs can possibly be worth if you are not ready to suffer or die for them."

"I am not going to beg for leniency. Everything is already clear. A court of occupiers cannot be just by definition," he told the judges, his last words before being handed a 20-year jail sentence with hard labour.

Sentsov has become a living symbol of the struggle in Ukraine and Crimea for its sovereignty and independence. Illienko thinks lesser mortals would have done anything to regain their freedom but Sentsov has stuck to his principles and does not recognise the powers of the court and judge that tried him.

"He is not a terrorist, he is a filmmaker," Illienko protests. He says of his declaration in court, "we are all proud of him and hope that he will soon be released". Illienko stresses the need for the international community to continue to put pressure on Russian authorities to release Sentsov even though he holds very little hope this will happen soon.

Who is Oleg Sentsov?

According to his IMDb profile, Sentsov, best-known for his 2011 film Gamer, was arrested by the Russian FSB (Federal Security Service) in his house in Simferopol in Crimea on 11 May 2014 and taken to Moscow and detained in the Lefortovo prison.

On 30 May 2014 the FSB announced that Sentsov - who had actively opposed Russia's annexation of Crimea by delivering food supplies to Ukrainian army troops trapped in their barracks - would be charged with planning to bomb with home-made devices two World War II monuments and setting fire to other buildings.

Sentsov denied all charges and called them insulting. After more than a year of legal prosecution, Sentsov was sentenced in August 2015 to 20 years imprisonment on charges of terrorism and terrorist organising. Sentsov, 39, a father-of-two has rejected the court ruling and continues to plead his innocence.

The trial was condemned by Amnesty International and other human rights' groups as a farce. The United States and the European Union have officially classified the ruling as unfair, referring to Sentsov not as a prisoner but as a Ukrainian hostage being held by the Russian military. The EU's foreign policy chief, Federica Mogherini, said the case breached international law, while the US ambassador to Ukraine, Geoffrey Pyatt, said the process had been a "farce".

The soft power of Ukraine

There is more to Ukraine than just civil uprisings and war, what about its soft power? Illienko says: "It is the art and cinema in particular that can best represent a country abroad. Events such as the Days Of Ukrainian Cinema in London contribute to the promotion of Ukrainian cinema and strengthening the favourable image of Ukraine."

Igor Iankovskyi, founder of charity Initiative For the Future, is behind Ukrainian Cinema Days in London, an event showcasing some of the best cinematic talents and productions emerging from the country.

He says: "My opinion is that there is a lack of information about my country, all that you know is the corruption and war but there is so much more going on, we are doing very good movies which you will see in the films showing in London. I want people to know more about us from different sides, not only from one side that is in newspapers and on television."

The Ukraine government's annual contribution to the country's film budget is a paltry $4m (£2.64m) but Iankovskyi believes though it is not much, it helps to start some projects and helps move them forward telling stories that might otherwise be forgotten. They have already taken the cinema roadshow to Paris and Munich where he says the offerings received rave reviews and showed to packed audiences.

Even though he was not sure what moviegoers would make of the films, Iankovskyi says "people were sitting between the aisles. The interest was unbelievable not only from the Ukrainians who lived there but from the French and Germans."

Iankovskyi hopes to get the same reception in London. He says his foundation, apart from projecting a positive image of Ukraine, wants to promote new film talent and fund new movies.

"The strategy of our foundation is to support talented young people. Modern, young Ukrainian cinema is able to produce a high-quality and inspiring product. We can see how each year the professional level of our young directors increases as they find interesting topics and creatively represent them in film.

"Therefore, our foundation for the third consecutive year, is financing, in Ukraine, the National Short Film competition, organising the young filmmakers' trips to the largest film festivals in Berlin, Cannes and presenting the Days of Ukrainian Cinema in Munich, Paris and London."

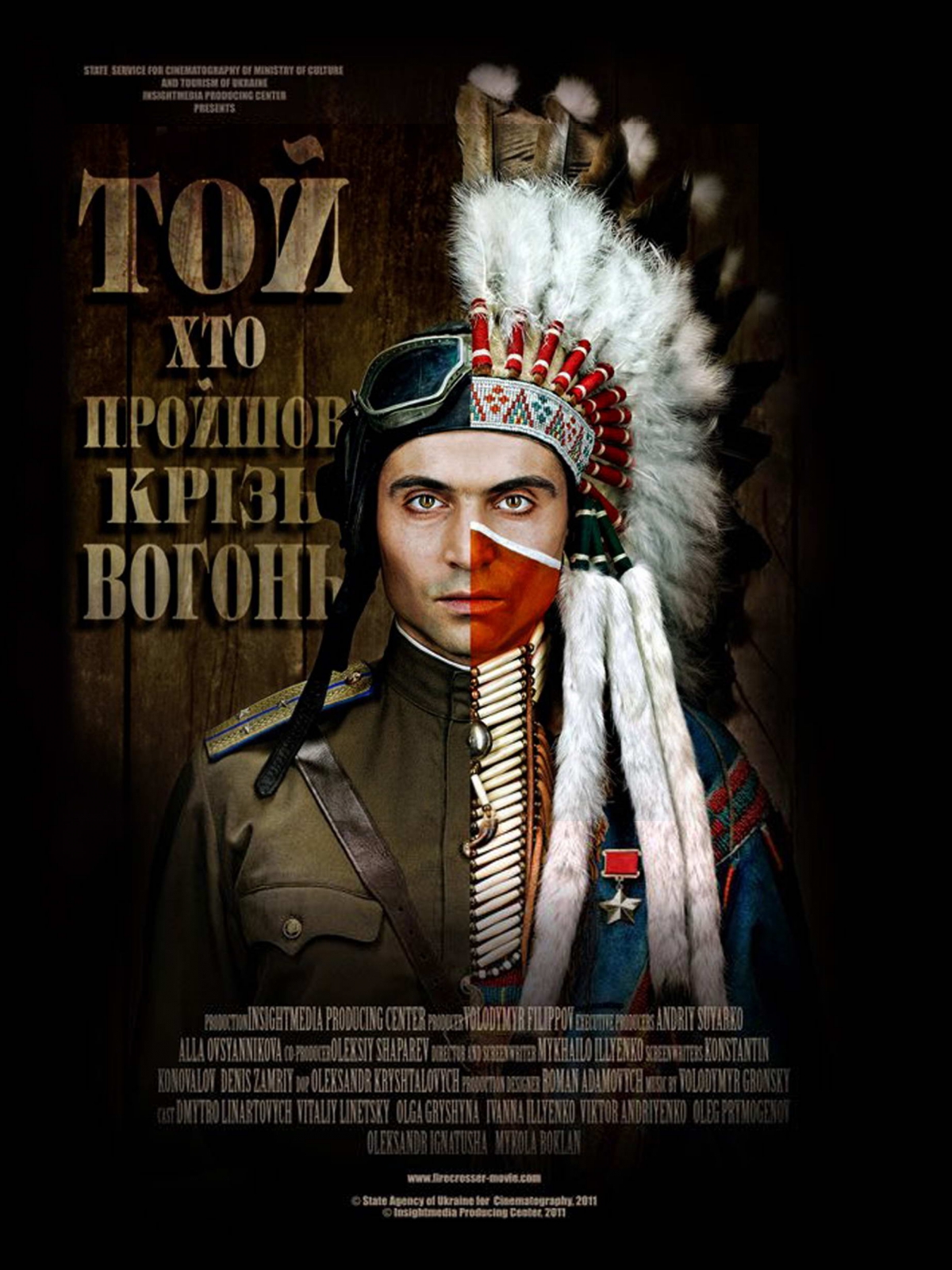

Firecrosser

Iankovskyi is full of praise for Firecrosser, a story based on true events when a Ukrainian-born Soviet pilot captured by the Nazis in the Second World War, becomes a Gulag prisoner but later escapes to become an Indian chief in Canada.

Iankovskyi wants the outside world to understand that despite the conflagrations in some parts of Ukraine, people still want to be entertained and still flock to the cinemas.

He explains: "As you know we have different parts of Ukraine, and the people are different, we are complex like the UK, made up of different sensibilities so when people go to see the movies, that connects all parts of Ukraine, which is most important right now.

"So everybody must understand that Ukraine is a solid state and that we are different but we are Ukrainians. This is the most important thing. The films are made in different parts of Ukraine and the cinemas are full all the time because the people are interested in what is going on in different parts of the country."

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.