Where Did Life Come from? Nasa's Water World Theory Explains Earth's Origins

Nasa have explained a theory which answers one of our biggest questions: How did life on Earth began?

A new study from researchers at Nasa's Jet Propulsion Laboratory has proposed the "water world" theory as the answer to our evolution, which describes how electrical energy naturally produced at the sea floor might have given rise to life.

While the hypothesis had already been proposed as "submarine alkaline hydrothermal emergence of life", the new report has unified years of field, laboratory and theoretical research into a grand picture.

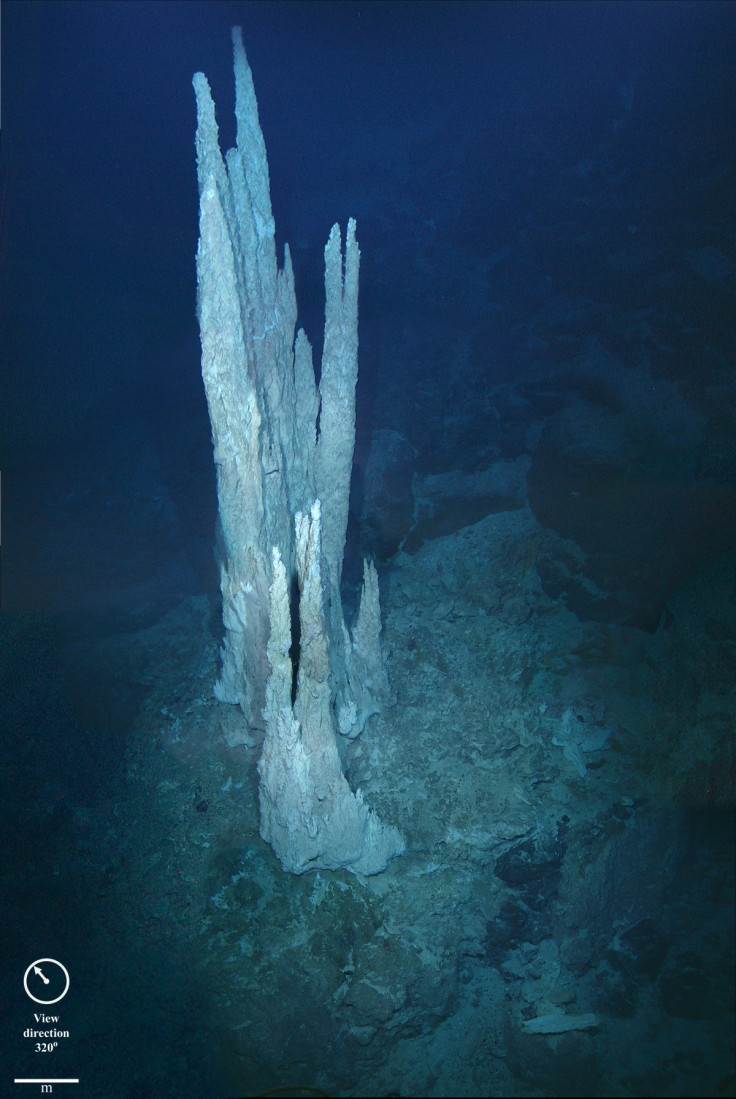

The findings suggest that life may have begun inside warm, gentle springs on the sea floor, which bubbled billions of years ago when Earth's oceans took over the whole planet. The springs - as opposed to the scalding hot, acidic hydrothermal vents proposed by researchers in the 1980s - are cooler and alkaline.

One example of these alkaline vents, which was dubbed the Lost City, was found by accident in the North Atlantic ocean in 2000.

Michael Russell, a scientist at the laboratory and the lead author of the study, said: "Life takes advantage of unbalanced states on the planet, which may have been the case billions of years ago at the alkaline hydrothermal vents. Life is the process that resolves these disequilibria."

The water world theory suggests that the warm, alkaline hydrothermal vents maintained an unbalanced state with respect to the surrounding ancient, acidic ocean - one that could have created two chemical imbalances.

The first was a proton gradient, where hydrogen ions were concentrated more on the outside of the vent's chimneys. The proton gradient could have been tapped for energy, in the same way our own bodies do in our cellular structures called mitochondria.

The second imbalance may have concerned the electrical gradient between the hydrothermal fluids and the ocean. Billions of years ago, when Earth was young, its oceans were rich with carbon dioxide. When the carbon dioxide from the ocean and hydrogen and methane from the vent met across the chimney wall, electrons may have been transferred.

These reactions could have produced more complex carbon-containing, or organic compounds, essential ingredients of life as we know it.

Laurie Barge, the second author of the study, explained: "Within these vents, we have a geological system that already does one aspect of what life does. Life lives off proton gradients and the transfer of electrons."

In our ancient oceans, minerals may have acted like enzymes to create chemical reactions. Russell added that these "mineral engines" are comparable to what is in modern cars.

"They make life 'go' like the car engines by consuming fuel and expelling exhaust. DNA and RNA, on the other hand, are more like the car's computers because they guide processes rather than make then happen."

One of the tiny engines is thought to have depended on a rare metal called molybdenum. This metal is also at work in our bodies, in a variety of enzymes. It assists with the transfer of two electrons at the same time rather than the usual one, which is useful in driving certain key chemical reactions.

"We call molybdenum the Douglas Adams element," said Russell, explaining that the atomic number of molybdenum is 42, which also happens to be the answer to the "ultimate question of life, the universe and everything" in Adams' popular book, "The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy." Russell joked, "Forty-two may in fact be one answer to the ultimate question of life!"

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.