Antibiotic resistance genes discovered in 900-year-old Incan mummy

Antibiotic-resistance genes have been discovered in a 900-year-old Incan mummy. The finding suggests these genes were present in the human gut long before the introduction of antibiotics.

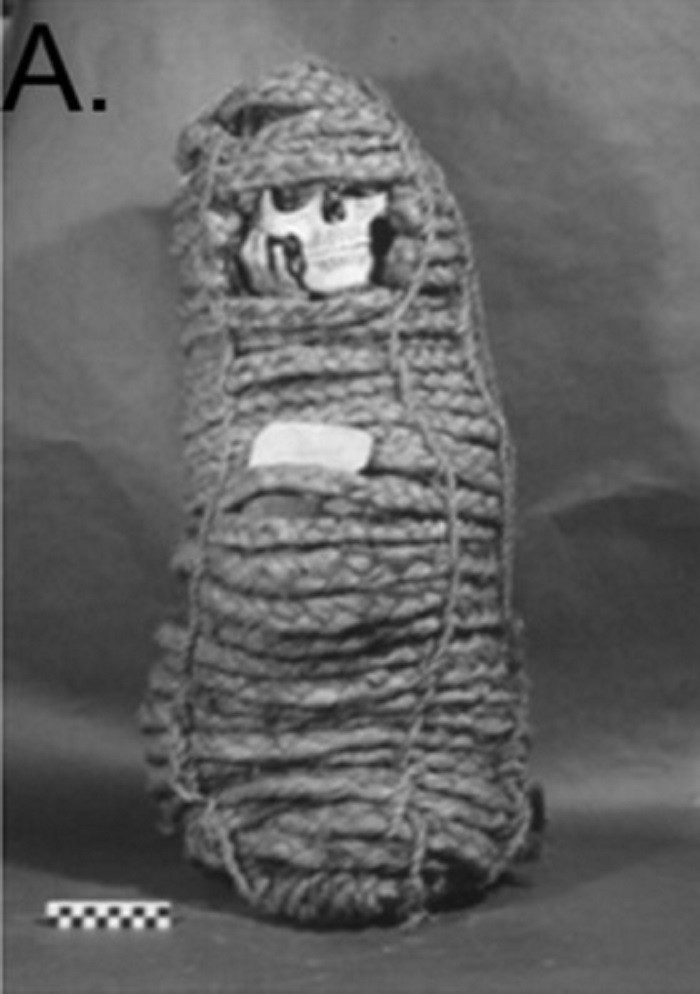

An international team of scientists examined the naturally mummified paleo-faeces found in the colon of the 11<sup>th century pre-Columbian Andean mummy. Findings, published in the journal PLOS One, also indicate that antibiotic resistance is not entirely the result of over and misuse of antibiotics.

The mummy analysed was found in Cuzco, the capital of the ancient Incan empire. It had been mummified in the Andes. In the 19<sup>th century it was taken to Italy and was later donated to the Museum of Anthropology and Ethnology of the University of Florence.

In the study, researchers used gene sequencing and metagenomics to identify bacterial groups in the mummy. They said the microbiome profile of the specimen was unique compared to mummies that had not been mummified naturally and that their analysis showed a number of DNA sequences homologous to Clostridium botulinum, Trypanosoma cruzi and human papillomaviruses (HPVs).

"The presence of putative antibiotic-resistance genes suggests that resistance may not necessarily be associated with a selective pressure of antibiotics or contact with European cultures."

Gino Fornaciari, from the University of Pisa, told Discovery News that the mummy was that of a female who died between the ages of 18 and 23. Her heart, oesophagus and colon were abnormally enlarged – and the latter had a huge amount of faeces within it. She likely died after being bitten by kissing bugs, triatominae. "It is very likely that Chagas' disease was the cause of death for the young woman," Fornaciari said.

Of the antibiotic resistance genes, scientists said the presence of vancomycin was of particular note: "Vancomycin was discovered more than 50 years ago, and vancomycin-resistant genes have been mainly implicated with the increased use of this antibiotic," they wrote.

"Identification of pathogens and antibiotic-resistance genes in ancient human specimens will aid in the understanding of the evolution of pathogens as a way to treat and prevent diseases caused by bacteria, microbial eukaryotes and viruses."

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.