Type-1 diabetes: Artificial pancreas close to public release as device moves to final clinical trials

A device acting as an artificial pancreas has got to pass two more stages of testing before being approved for used by the public. It was developed to stop the need for manual injections in diabetes sufferers, which could be needed multiple times per day.

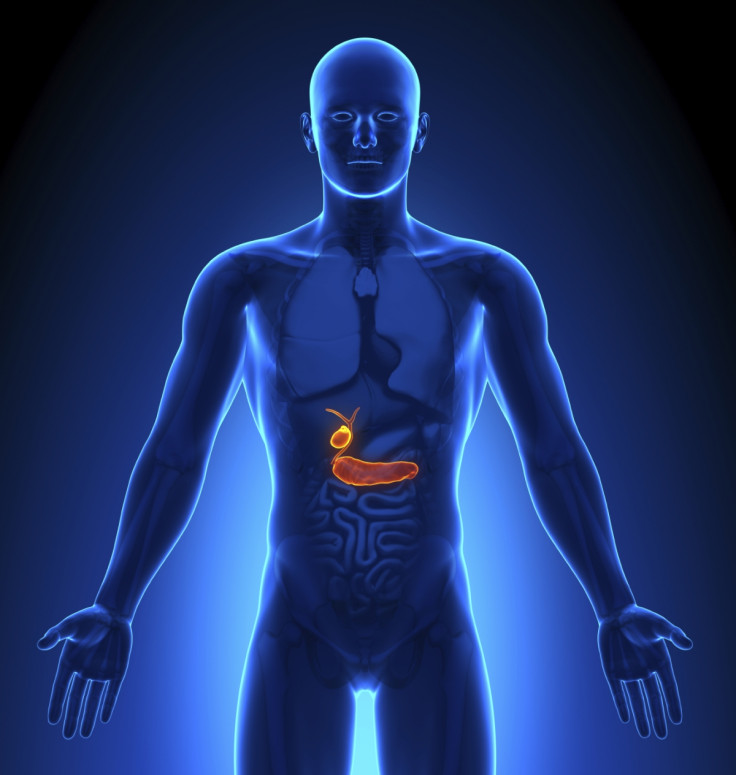

The artificial pancreas works by self-regulating the hormone insulin in the body of Type-1 diabetics. The device automatically detects when the body needs more insulin, and increases the amount of the hormone accordingly. Likewise, when there is too much, it will decrease the amount.

"To be ultimately successful as an optimal treatment for diabetes, the artificial pancreas needs to prove its safety and efficacy in long-term pivotal trials in the patient's natural environment," said Boris Kovatchev, lead researcher of the artificial pancreas from the University of Virginia. "The artificial pancreas is not a single-function device; it is an adaptable, wearable network surrounding the patient in a digital treatment ecosystem."

The device itself uses algorithms used in the continued running of smartphones, redesigned for use as a pancreas. It is wirelessly connected to a blood-sugar monitor and an insulin pump.

In order to be approved by the US Food and Drug Administration, the device needs to pass two long-term clinical trials. These trials will be conducted in nine different locations across the USA and Europe.

The first test, known as the International Diabetes Closed-Loop trial, will use 240 patients with Type-1 diabetes to test the safety of the device compared to a standard insulin pump. Blood sugar-levels and the risk of hypoglycaemia will be analysed for six months, as participants carry on with their daily lives.

Following success of this stage, the invention will move to stage two, which involves following 180 of the patients from the first part of the study for a further six months. During this period, an equation developed by Harvard University will be tested to see if it increases control of blood sugar levels.

The World Health Organization estimates that by 2030, the number of diabetes sufferers will reach 366 million people worldwide. That is more than twice the number of sufferers recorded in the year 2000.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.