Assad and Isis are Two Sides of the Same Vile Coin - and Cameron Must Not Forget it

"There's an elephant in the room," proclaimed Peter Hain last week on Newsnight. An elephant in the shape of Bashir al-Assad, the president of what remains of the Syrian Republic.

As Nato leaders discuss how to respond to the bloody rise of Islamic State (formerly Isis), grandees from all the parties are calling for a radical rethink. Hain, Malcolm Rifkind, Lord West and Andrew Mitchell have emerged into the media spotlight to advocate engaging with al-Assad and even coordinating military action with his regime.

These politicians are pressing the UK government to hold its nose and engage diplomatically with a man described by David Cameron as a "tyrant". A leader who is directly held accountable by the UK government for launching the largest chemical weapons attack since the late 1980s.

And it's not just politicians recommending what would be a remarkable U-turn. Sir William Patey, a former British ambassador to the region renowned within the Foreign Office as an expert orientalist, is taking to the airwaves to argue the same approach.

But is it feasible to engage with a man presented to us as a monster? Or was the narrative of Assad "the monster" convenient at a time when politicians were looking to be on the right side of history at the height of the Arab Spring?

Since 2002, there had been a train of thought in Whitehall and the State Department that Assad could be turned. That his allegiance with Hezbollah and their Iranian masters was merely a marriage of convenience. That his true intentions could be divined not through intelligence briefings or the reports from dissidents, but from his actions.

From banking sector reform in partnership with British banks, to the opening of the stock exchange in Damascus with American expertise, and the building of a gargantuan General Motors showroom near the capital, Western governments were determined to chip away at the formerly pro-Russian regime and mould a respectable partner.

And so the visits intensified. MPs, congressmen, defence officials and business delegations flew in. They all took the 15-minute car journey to the Presidential Palace compound at the heart of Damascus' government quarter, which would not look out of place in a Bond film.

A luscious, Persian (what else?) red carpet takes visitors past monstrous pillars and exquisite statues to the reception room. And standing in the shadow of the enormous, ornate door would be the man himself, who always insisted on greeting visitors personally. Surprisingly tall himself, most people were generally struck by two features: his striking blue eyes and his perfect English.

They shouldn't have been surprised. He wasn't always an autocrat. Growing up, he was the second son of Hafez al-Assad, and never expected to take control of the Alawite dynasty – that was his brother's fate. Instead, he pursued a medical degree and practised ophthalmology in London.

There he met his wife, Asma, who was carving out a successful career at Goldman Sachs. Quite literally, everything changed in a flash. His brother was assassinated in a car bomb attack. Reluctantly, he returned home to continue his family's legacy.

Assad comes across as anything other than a monster. He's charismatic, funny, engaging and obviously intelligent. His wife is similar. She is beguiling in her apparent passion for children's education, and her love of London and the British people shines through.

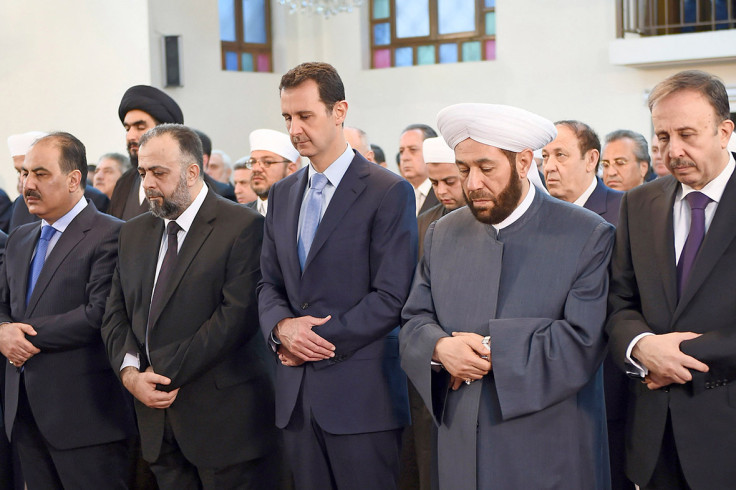

In some ways the Assads are everything British politicians would have wanted in the Syrian leadership today. Anglophiles, Westernised, with a cursory nod towards the Islamic faith and a love of Liberty. Not the ideal, of course, but the luxury London store.

They seem a world away from the barbarous Isis extremists. The Assads understand diplomatic processes, even if they don't abide by them. They can be negotiated with, and, after all, our enemy's enemy is surely our friend?

But, of course, the Assads are not particularly different from the IS militants beating a path to their ornate door. And while Philip Hammond and Cameron, George Osborne and Nick Clegg consider their options, they should remember Assad's brand of urbane murder is still murder. Murder committed in a suit in Damascus is no different to murder committed in combat fatigues in the stark Syrian desert.

So as Hain and others ponder that there was once a time that Assad perhaps wasn't as bad as we thought, and think a "real politick" arrangement should be sought, we should remind them of crimes committed by a regime steeped in criminality and bloodshed.

That engagement with Bashir al-Assad would be a betrayal of the countless Syrians murdered under his orders. The lessons of British history, littered with failed engagements with dictators, should be the real elephant in the room.

Ross Cypher-Burley is a former spokesman for the British ambassador to Israel, and now works for political consultancy firm Portland Communications. You can follow him on Twitter here.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.